The cloud was discovered in the early 1960s by doctoral astronomy student Gail Smith, who detected the radio waves emitted by its hydrogen.

Washington:

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has spotted a monstrous cloud of hydrogen gas that is plummeting toward our galaxy at nearly 1.1 million km per hour.

Though hundreds of enormous, high-velocity gas clouds whiz around the outskirts of our galaxy this so-called "Smith Cloud" is unique because its trajectory is well known.

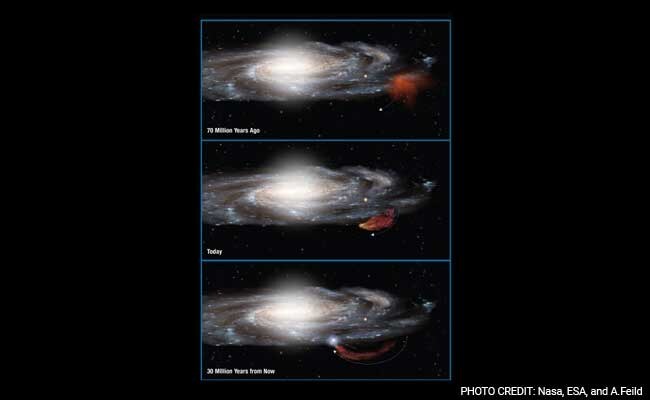

New Hubble observations suggest it was launched from the outer regions of the galactic disk, around 70 million years ago.

The cloud was discovered in the early 1960s by doctoral astronomy student Gail Smith, who detected the radio waves emitted by its hydrogen.

The cloud is on a return collision course and is expected to plow into the Milky Way's disk in about 30 million years.

When it does, astronomers believe it will ignite a spectacular burst of star formation, perhaps providing enough gas to make two million Suns.

"The cloud is an example of how the galaxy is changing with time. It's telling us that the Milky Way is a bubbling, very active place where gas can be thrown out of one part of the disk and then return back down into another," explained team leader Andrew Fox of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

Our galaxy is recycling its gas through clouds, the Smith Cloud being one example, and will form stars in different places than before.

"Hubble's measurements of the Smith Cloud are helping us to visualise how active the disks of galaxies are," Fox added in a NASA statement.

Astronomers have measured this comet-shaped region of gas to be 11,000 light-years long and 2,500 light-years across.

If the cloud could be seen in visible light, it would span the sky with an apparent diameter 30 times greater than the size of the full moon.

The team used Hubble to measure the Smith Cloud's chemical composition for the first time, to determine where it came from.

They observed the ultraviolet light from the bright cores of three active galaxies that reside billions of light-years beyond the cloud.

The astronomers found that the "Smith Cloud" is as rich in sulphur as the Milky Way's outer disk, a region about 40,000 light-years from the galaxy's centre (about 15,000 light-years farther out than our sun and solar system).

This means that the "Smith Cloud" was enriched by material from stars. This would not happen if it were pristine hydrogen from outside the galaxy, or if it were the remnant of a failed galaxy devoid of stars.

"Instead, the cloud appears to have been ejected from within the Milky Way and is now boomeranging back," the authors noted in a paper appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Though hundreds of enormous, high-velocity gas clouds whiz around the outskirts of our galaxy this so-called "Smith Cloud" is unique because its trajectory is well known.

New Hubble observations suggest it was launched from the outer regions of the galactic disk, around 70 million years ago.

The cloud was discovered in the early 1960s by doctoral astronomy student Gail Smith, who detected the radio waves emitted by its hydrogen.

The cloud is on a return collision course and is expected to plow into the Milky Way's disk in about 30 million years.

When it does, astronomers believe it will ignite a spectacular burst of star formation, perhaps providing enough gas to make two million Suns.

"The cloud is an example of how the galaxy is changing with time. It's telling us that the Milky Way is a bubbling, very active place where gas can be thrown out of one part of the disk and then return back down into another," explained team leader Andrew Fox of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

Our galaxy is recycling its gas through clouds, the Smith Cloud being one example, and will form stars in different places than before.

"Hubble's measurements of the Smith Cloud are helping us to visualise how active the disks of galaxies are," Fox added in a NASA statement.

Astronomers have measured this comet-shaped region of gas to be 11,000 light-years long and 2,500 light-years across.

If the cloud could be seen in visible light, it would span the sky with an apparent diameter 30 times greater than the size of the full moon.

The team used Hubble to measure the Smith Cloud's chemical composition for the first time, to determine where it came from.

They observed the ultraviolet light from the bright cores of three active galaxies that reside billions of light-years beyond the cloud.

The astronomers found that the "Smith Cloud" is as rich in sulphur as the Milky Way's outer disk, a region about 40,000 light-years from the galaxy's centre (about 15,000 light-years farther out than our sun and solar system).

This means that the "Smith Cloud" was enriched by material from stars. This would not happen if it were pristine hydrogen from outside the galaxy, or if it were the remnant of a failed galaxy devoid of stars.

"Instead, the cloud appears to have been ejected from within the Milky Way and is now boomeranging back," the authors noted in a paper appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world