A few friends were discussing the surgical strike the other day when one of them asked what it must be like for families of our armed forces personnel who are called into action. What do they go through? How do they cope with the tension of separation brought about by lengthy deployments and actual engagement? How do families get on with life with their husbands, fathers, sons and brothers, (soon it will be daughters and wives and sisters too) away on the borders and other active locations?

Being the son of an army officer, the late General K V Krishna Rao, PVSM, former Chief of the Army Staff and Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee, I know what our family went through at various times in my father's long and illustrious career, first as an army man and later as Governor in what were categorized as "difficult states".

Of course most armed forces personnel and their families have all gone through trying living conditions in extremely difficult and unfamiliar areas with very poor education and commercial facilities, virtually cut off from the state one belongs to and the more urban parts of the country. And yes, even locations like Ambala, Udhampur and Jammu were difficult to live in when I was a boy. But we were all together as a family and we loved being wherever we were because home is where the heart is. It was, however, a different thing when my father was posted in a "field" area where families weren't allowed and we had to live separately.

In 1965, when I was 11, my sister 8, and my mother 32, my father was posted to Chushul in Ladakh to command a brigade on the front with China. The formation was located at a height of 17,000 feet with winter temperatures going down to -40 degrees Celsius. His troops were at pickets that went up to 20,000 feet. We were in Chennai and saw my father two times a year when he came home on leave. There were no mobiles or even a telephone system then; the only communication was by letters which took a month to reach. Tense family events and situations were rarely communicated, and it was left to my mother to take most of the decisions that affected her and us. That included illness and injuries. Often there were financial problems and my mother was a housewife with no independent source of income. We hardly ever got to know how my father was except when the eagerly awaited letters got to us, but we lived in the knowledge that he must have been ok - else someone would have got in touch! At good times, there would be an officer on leave or temporary duty in Chennai and then letters and goodies like namkeen were lovingly bought and sent to my father by hand. It was a difficult time for the family, in particular for a young woman and her children, but she and we handled it quite well.

In 1970, my father became a Major General and was put in command of the iconic 8 Mountain Division, then located in Zakhama in Nagaland. The Naga insurgency was at its peak at the time and his responsibilities and their implication on the nation were huge. His personal security was also at risk. Our family again got "separated" and we lived in Secunderabad at this time. While letters still needed to be written, we now had a telephone at home and once a fortnight or so, my father would make a trunk call and have a three-minute conversation with my mother. Of course the lines needed to be good and quite often he could not get through. When on leave, every evening a dispatch rider would come home and deliver a SITREP (Situation Report) which would tell him about goings on in Nagaland. The situation there was fluid and tense. And we were growing up without our father.

In 1970, my father became a Major General and was put in command of the iconic 8 Mountain Division, then located in Zakhama in Nagaland. The Naga insurgency was at its peak at the time and his responsibilities and their implication on the nation were huge. His personal security was also at risk. Our family again got "separated" and we lived in Secunderabad at this time. While letters still needed to be written, we now had a telephone at home and once a fortnight or so, my father would make a trunk call and have a three-minute conversation with my mother. Of course the lines needed to be good and quite often he could not get through. When on leave, every evening a dispatch rider would come home and deliver a SITREP (Situation Report) which would tell him about goings on in Nagaland. The situation there was fluid and tense. And we were growing up without our father.

In May 1971, I was traveling near Coimbatore by train with a friend and since we did not have a reservation, we were sitting at the open door of the unreserved compartment with our legs hanging out, feet on the footboard. All of a sudden, the express train passed through a station at speed and we got caught between the train and the platform, getting dragged along the platform. Our injuries were ghastly and we had to get off the train a few minutes later at Coimbatore for immediate medical attention. A couple of friends also disembarked to help us; we were taken to the nearest service hospital, which was the Air Force Hospital at Coimbatore.

My injuries were very serious and I remained at the hospital at Coimbatore and later, Wellington near Ooty, for about three weeks before they were able to transfer me to the Command Hospital at Pune for complicated surgery. However, my father's division was assigned an important role for what was later the Indo-Pak war of 1971 and they were in preparation mode by then. He could not come from Nagaland to visit me. Nor could my mother from Secunderabad. So there I was, all of 17, hospitalised with very serious injuries and no parent with me. I have to admit that I resented it initially, but soon understood, and accepted the compulsions of my parents at the time. My father had a vital national role and my mother had to look after my sister. Of course they were able to see me in due course of time. Later, when I was discharged from hospital and ready to join college, my father could not be with me for the same reason. In December 1971, 8 Mountain Division went into Bangladesh and was successful in the capture of Sylhet along with a large number of Pakistani POWs. Col Zia Ur Rehman, later President of Bangladesh, was attached to my father's division during the war. I felt very proud when my father was awarded his PVSM (Param Vishisht Seva Medal) for "displaying outstanding leadership, courage, determination and drive" during this War.

The following year, in 1972, I had another accident and was sent to the army orthopedic hospital at Kirkee near Pune for treatment that included surgery. Though the war was over, my father was by now posted to Simla as Chief of Staff Western Command and was involved with the disengagement and strategic aspects of the Simla Agreement. He could not visit me again, but I stopped feeling sorry for myself the moment I reached Kirkee. Though my injuries were bad, they paled into insignificance at the sight of the other patients there. Virtually everyone at the hospital was a war veteran and had suffered their injuries as a result of it. I came across multiple bullet and shelling wounds, amputations coupled with blindness, paraplegic servicemen, all permanently disabled. Everyone was suffering their pain and injuries in a most stoic manner, never regretting or bemoaning their fate and proud of their contribution to the war effort and national cause. Their patriotism was astounding and admirable. I felt ashamed at my own injuries resulting from teenage foolishness while here were people not much older than me who had given up their present and future for the country.

The following year, in 1972, I had another accident and was sent to the army orthopedic hospital at Kirkee near Pune for treatment that included surgery. Though the war was over, my father was by now posted to Simla as Chief of Staff Western Command and was involved with the disengagement and strategic aspects of the Simla Agreement. He could not visit me again, but I stopped feeling sorry for myself the moment I reached Kirkee. Though my injuries were bad, they paled into insignificance at the sight of the other patients there. Virtually everyone at the hospital was a war veteran and had suffered their injuries as a result of it. I came across multiple bullet and shelling wounds, amputations coupled with blindness, paraplegic servicemen, all permanently disabled. Everyone was suffering their pain and injuries in a most stoic manner, never regretting or bemoaning their fate and proud of their contribution to the war effort and national cause. Their patriotism was astounding and admirable. I felt ashamed at my own injuries resulting from teenage foolishness while here were people not much older than me who had given up their present and future for the country.

Being located in distant family stations had its own advantages. We saw places that we would ordinarily never visit. When my father commanded a Corps in Jammu and Kashmir from 1974-1978, I had the privilege of visiting places like Poonch, Rajauri, Akhnoor, Bhimbargali, Mehndar and Krishnaghati. All of these are the very areas from where the recent surgical strikes took place. Krishnaghati has a memorial dedicated to the victims of a helicopter crash that took the lives of six officers of the rank of General and equivalent on November 22, 1963. That was the same day that President Kennedy was assassinated and the newspapers of the next day could not do justice to the martyrs. I once visited a fort called Chingus Serai between Akhnoor and Rajauri which was constructed by Jehangir in the 16th century. It is said that on one journey from Srinagar, Jehangir died and his entrails were buried there. His death was not announced to prevent revolt, and his embalmed body was taken propped up on an elephant by Noor Jahan to Lahore where it was buried. So we have two graves for one man, one in Chingus and the other in Lahore. I would never have seen these places, rich in beauty and history, if my father had not been appointed GOC 16 Corps.

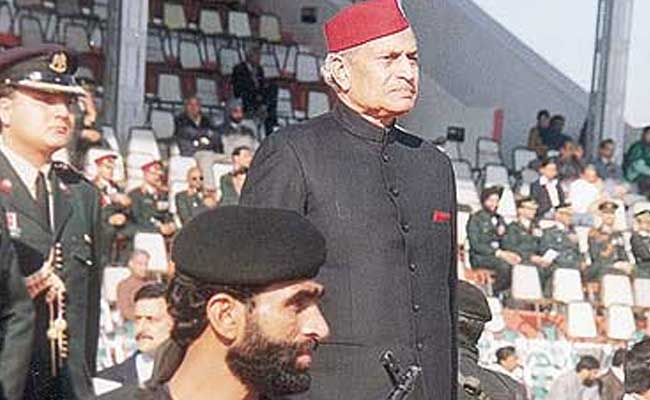

Much later, on 26 January 1995, when my father was the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir, there was an attempt on his life while he was addressing the gathering at the Republic Day Parade in Jammu. Three bombs were detonated but none could get him, though there were others who lost their lives that day. I remember receiving a call from my mother at about 10 that morning telling me that they had just got home from the parade which was curtailed as a result of the attempt. She said that they were fine and that we should not get worried when we see the news reports about the attempt. As all was well, we took the details in our stride.

I lost my mother in 2007 while my father passed away this year on Martyr's day. A few days back when I was going through a cupboard in my father's home in Secunderabad, I came across the saree my mother was wearing on 26 January, 1995. It had holes and burn marks in it from the acid that splashed onto her when some battery packs exploded that day at one of the bomb locations near where she was sitting. She had told me that they were fine that day. But were they really?

(KVL Narayan Rao is Executive Vice-Chairperson, NDTV.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Being the son of an army officer, the late General K V Krishna Rao, PVSM, former Chief of the Army Staff and Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee, I know what our family went through at various times in my father's long and illustrious career, first as an army man and later as Governor in what were categorized as "difficult states".

Of course most armed forces personnel and their families have all gone through trying living conditions in extremely difficult and unfamiliar areas with very poor education and commercial facilities, virtually cut off from the state one belongs to and the more urban parts of the country. And yes, even locations like Ambala, Udhampur and Jammu were difficult to live in when I was a boy. But we were all together as a family and we loved being wherever we were because home is where the heart is. It was, however, a different thing when my father was posted in a "field" area where families weren't allowed and we had to live separately.

In 1965, when I was 11, my sister 8, and my mother 32, my father was posted to Chushul in Ladakh to command a brigade on the front with China. The formation was located at a height of 17,000 feet with winter temperatures going down to -40 degrees Celsius. His troops were at pickets that went up to 20,000 feet. We were in Chennai and saw my father two times a year when he came home on leave. There were no mobiles or even a telephone system then; the only communication was by letters which took a month to reach. Tense family events and situations were rarely communicated, and it was left to my mother to take most of the decisions that affected her and us. That included illness and injuries. Often there were financial problems and my mother was a housewife with no independent source of income. We hardly ever got to know how my father was except when the eagerly awaited letters got to us, but we lived in the knowledge that he must have been ok - else someone would have got in touch! At good times, there would be an officer on leave or temporary duty in Chennai and then letters and goodies like namkeen were lovingly bought and sent to my father by hand. It was a difficult time for the family, in particular for a young woman and her children, but she and we handled it quite well.

In May 1971, I was traveling near Coimbatore by train with a friend and since we did not have a reservation, we were sitting at the open door of the unreserved compartment with our legs hanging out, feet on the footboard. All of a sudden, the express train passed through a station at speed and we got caught between the train and the platform, getting dragged along the platform. Our injuries were ghastly and we had to get off the train a few minutes later at Coimbatore for immediate medical attention. A couple of friends also disembarked to help us; we were taken to the nearest service hospital, which was the Air Force Hospital at Coimbatore.

My injuries were very serious and I remained at the hospital at Coimbatore and later, Wellington near Ooty, for about three weeks before they were able to transfer me to the Command Hospital at Pune for complicated surgery. However, my father's division was assigned an important role for what was later the Indo-Pak war of 1971 and they were in preparation mode by then. He could not come from Nagaland to visit me. Nor could my mother from Secunderabad. So there I was, all of 17, hospitalised with very serious injuries and no parent with me. I have to admit that I resented it initially, but soon understood, and accepted the compulsions of my parents at the time. My father had a vital national role and my mother had to look after my sister. Of course they were able to see me in due course of time. Later, when I was discharged from hospital and ready to join college, my father could not be with me for the same reason. In December 1971, 8 Mountain Division went into Bangladesh and was successful in the capture of Sylhet along with a large number of Pakistani POWs. Col Zia Ur Rehman, later President of Bangladesh, was attached to my father's division during the war. I felt very proud when my father was awarded his PVSM (Param Vishisht Seva Medal) for "displaying outstanding leadership, courage, determination and drive" during this War.

Being located in distant family stations had its own advantages. We saw places that we would ordinarily never visit. When my father commanded a Corps in Jammu and Kashmir from 1974-1978, I had the privilege of visiting places like Poonch, Rajauri, Akhnoor, Bhimbargali, Mehndar and Krishnaghati. All of these are the very areas from where the recent surgical strikes took place. Krishnaghati has a memorial dedicated to the victims of a helicopter crash that took the lives of six officers of the rank of General and equivalent on November 22, 1963. That was the same day that President Kennedy was assassinated and the newspapers of the next day could not do justice to the martyrs. I once visited a fort called Chingus Serai between Akhnoor and Rajauri which was constructed by Jehangir in the 16th century. It is said that on one journey from Srinagar, Jehangir died and his entrails were buried there. His death was not announced to prevent revolt, and his embalmed body was taken propped up on an elephant by Noor Jahan to Lahore where it was buried. So we have two graves for one man, one in Chingus and the other in Lahore. I would never have seen these places, rich in beauty and history, if my father had not been appointed GOC 16 Corps.

Much later, on 26 January 1995, when my father was the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir, there was an attempt on his life while he was addressing the gathering at the Republic Day Parade in Jammu. Three bombs were detonated but none could get him, though there were others who lost their lives that day. I remember receiving a call from my mother at about 10 that morning telling me that they had just got home from the parade which was curtailed as a result of the attempt. She said that they were fine and that we should not get worried when we see the news reports about the attempt. As all was well, we took the details in our stride.

I lost my mother in 2007 while my father passed away this year on Martyr's day. A few days back when I was going through a cupboard in my father's home in Secunderabad, I came across the saree my mother was wearing on 26 January, 1995. It had holes and burn marks in it from the acid that splashed onto her when some battery packs exploded that day at one of the bomb locations near where she was sitting. She had told me that they were fine that day. But were they really?

(KVL Narayan Rao is Executive Vice-Chairperson, NDTV.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world