Punjab is a state where the BJP hasn't mattered much, and the Congress and the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) matter a lot. Or at least, that was the case until 2017, when Arvind Kejriwal's upstart party AAP queered the pitch and came in second, pushing the Akalis and their ally BJP to a humbled third. That AAP didn't do as well as many observers (including this one) had expected, has been put down to a last-minute Congress surge.

As Punjab votes again tomorrow, will the Arvind Kejriwal 'terrorist' controversy derail AAP this time?

In the five years since 2017, much has changed and much has remained the same. The ruling Congress sacked its winning Chief Minister Captain Amarinder Singh four months ago and is now led by a Dalit for the first time. Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi leads a faction-riven party facing corruption charges and the burden of maladministration. Yet the Congress remains a contender.

The Akalis, who split from the BJP during the farmers' agitation, have added the BSP to their camp in the hope of gaining Dalit votes to boost their appeal. The BJP, battered by the famers' agitation, has brought in Amarinder Singh and his new party as an ally and is contesting all the seats for the first time. Like everywhere else, the BJP's plank is twin-engine development and religious connections. But the big story in Punjab remains AAP and what it can or cannot do.

The party is back after performing very badly in the 2019 general election. It has named its sole MP, former comedian Bhagwant Mann, as its presumptive Chief Minister.

That is something it did not do in 2017 and people said that hurt the party a lot.

It is better organized, has better known candidates (defectors too), and most importantly, is much, much better funded. To butcher the 19th century ditty - they (AAP) want to fight...they have the guns, they have the men and the money too. So can they do what they failed to do in 2017?

The Punjab election seemingly throws up three scenarios:

Scenario 1: The Congress limps back to power with a substantially reduced majority. The premise here is that the party that has maintained a steady vote share in the last four elections - around 36-40% of the vote - should win enough seats in what will be a fractured four-way vote split between the Congress, SAD, BJP+ and AAP.

While a four-way split would lower the winning percentage required for a seat to well below 40%, and seemingly help the Congress, the fact is that in 2017, AAP seems to have gained the least from the Congress and most from the Akalis.

This time, will AAP cut into Congress' vote?

The anti-incumbency factor would suggest that the Congress would lose support. The question is whether the level of decline is enough to cost its majority. This is where the party should worry.

In 2017, almost half the seats in Punjab were won by margins of less than 10%. Of these, 31 were Congress victories. More worrying for the Congress - 23 of these were by margins of less than 8%. These are seats that could fall if just a couple of thousand voters switched sides. In fact, just 20,000 votes, spread evenly across these 26 seats, could bring the party below the magical majority number of 58. That's not a lot of people, given anti-incumbency and the battle cry of "change".

The Congress' return to power then rests on the Captain weaning away very few votes, and AAP continuing to make its gains at the expense of the Akalis.

Scenario 2: A hung assembly is the most plausible result if the Akalis don't lose too much ground and the swing against the Congress is not more than 5%. That would (see table above) see the Congress holding the seats with majorities above 10%, which means between 40-46 seats.

If the Akalis retain their 15 seats from the last time, and with BSP support in the high Dalit region of Malwa, they could repeat their performance of Lok Sabha 2019 and get 25+ seats. Assuming that the BJP holds on to its urban seats and Amarinder Singh picks up a couple in home ground Patiala, that would keep AAP under 60 seats.

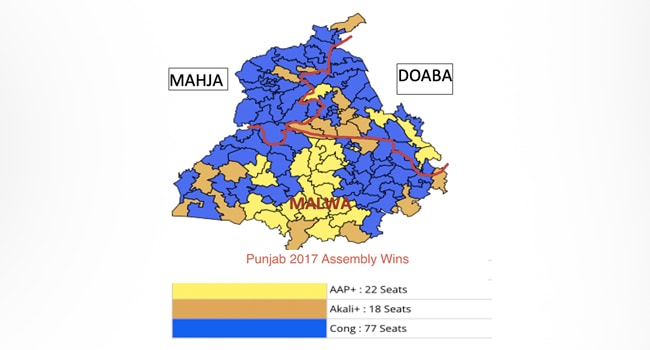

That is not the only reason that many voters feel the Sunday vote will throw up a cocktail. A part of the problem AAP+ had in 2017 was that it was largely confined to the Malwa region; it won 18 of its 22 seats here. (see map below)

The other issue for AAP is that it was runner up in only 26 seats - far fewer than the Akalis. The good news is that 23 of them were against the Congress, which it hopes is losing ground.

But even if it does win all 26, it needs something more to push it to an outright victory.

Scenario 3: AAP wins a majority and forms a government in a proper state (Delhi is a state where the powers of the Chief Minister are restricted by the Lieutenant Governor) with a wave in its favour. This is what AAP supporters believe is happening on the ground. They strongly believe change is on its way. As one supporter said, in his lifetime he has seen 10 years of Akalis and 10 years of Congress, now it is time for something new. Is AAP that something?

In the 26 seats it came second it needs an average of 5,000 votes to shift. That's within the 5% swing but is the demand for change that strong? Even if it is, that would still leave AAP short of a majority.

AAP needs to expand its footprint beyond the Malwa region; 19 of the 26 seats where it placed second are also in this region.

The big opportunity for AAP lies in urban Punjab. Pushing its "Delhi model", which seems to have resonance in Punjab, this is where AAP can "showcase" what it has achieved in Delhi in terms of infrastructure, health, education, and sanitation, all that Punjab towns seem to lack copiously.

AAP struggled in urban areas in 2017. It won three seats (two won by its ally) and didn't even come second in most others. That was a terrible performance, given that it is basically an urban Delhi party. This is where its salvation may lie in 2022 - it has, like in Delhi, a "corrupt Congress government" to topple in Punjab. It has done it before, can it again?

Or will this sudden revelation of Arvind Kejriwal as a 'secessionist' scare voters away at the last moment? The way the Congress and BJP are using his alleged remarks clearly indicates they are worried about AAP's possible performance.

Now Punjab is state where voters take their vote seriously, especially in an assembly election. The turnout has been 75%+ in the last three assembly elections.

So look to see what the turnout is. If there is a jump, especially in urban areas, then perhaps change is happening. If not, it could be a cocktail.

(Ishwari Bajpai is Senior Advisor at NDTV.)

Disclaimer: These are the personal opinions of the author.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world