Cast: Sanjay Mishra, Ranvir Shorey, Tillotama Shome, Bhupesh Singh, Ekta Sawant

Director: Nila Madhab Panda

Rating: 3.5 Stars (out of 5)

Nila Madhab Panda's Kadvi Hawa is a pill so bitter that no palliative can lessen the sharp aftertaste that it leaves. And that is precisely what this film is meant to do: force the audience to think long and hard about the dangers that lie ahead of mankind if climate change isn't taken seriously and addressed on a war footing at all levels. Delivered without any sugar-coating, Kadvi Hawa blows the lid off our collective indifference to the worsening impact of wobbly weather systems on lives and livelihoods in ecologically vulnerable regions.

Kadvi Hawa Movie Review: Sanjay Mishra in a film still.

Notwithstanding the slight hint of humour that the screenplay occasionally injects into this story about severely ravaged communities, it is a film that pulls no punches in painting a disturbingly dark picture of the human cost of the cavalier collective disregard of the continuing depletion of finite natural resources.

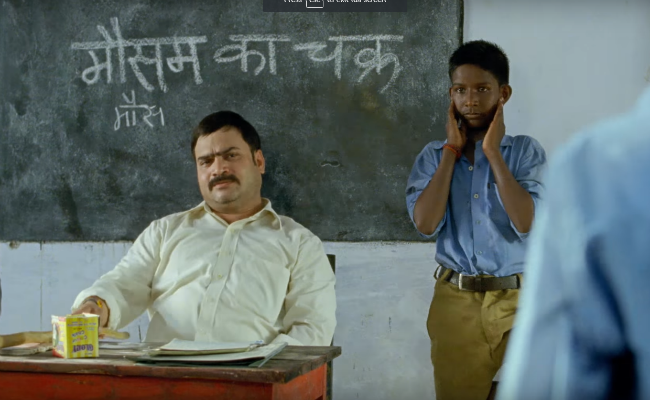

In one scene, a teacher asks a school student how many seasons there are. "Summer and winter," the boy answers. What about the monsoon? "It does rain two or three days a year, sometimes in winter, sometimes in summer," he replies, provoking peals of laughter from his classmates. It is the chilling truth and we know all too well that the scarcity of rain is no laughing matter.

Kadvi Hawa Movie Review: A still from the film.

Kadvi Hawa, shot on Super 16mm film that significantly accentuates the forbidding starkness of the landscape, delivers its cautionary tale with an unsettling air of urgency, which is heightened by the sheer power of a brilliant performance from Sanjay Mishra, who fleshes out the character of a sightless old man who, worried for his debt-ridden farmer-son and his family, strikes a deal with a pitiless man who, for the people of this village located off Dholpur, near Agra, is the Devil himself.

But as it turns out, the 'God of Death', who must do his job come what may as a loan recovery agent sent to this rain-deficient region to arm-twist farmers into clearing their outstanding debts, is himself a victim of the fury of nature unleashed by the sea in his native Kendrapara, Odisha. This character is played with energy and precision by Ranvir Shorey, who matches the incredibly impactful Mishra, moment for moment.

The two superlative performances lend Kadvi Hawa its heft. The director does not take recourse to over-dramatic means to convey the depth of despair that drives the two men into each other's orbit in circumstances that are so fast spinning out of control. One thinks that the other could be of help, but neither really knows where their lives are headed. They are both equally at the mercy of the elements and of a system low on humanity.

Kadvi Hawa Movie Review: Sanjay Mishra and Ranvir Shorey in a film still.

There is, on the face of it, no earthly reason - or, perhaps, there is - for their paths to cross. Hedu, 70 years old, blind and palpably helpless, is instinctive, enterprising and proud of his identity as a farmer despite the grave misfortunes that have befallen him. He lives in an area that hasn't received any rain in ages. He is acutely alive to the need to find a way around his wretched destiny.

His brooding son Mukund (Bhupesh Singh) barely utters a word. The old man keeps a tab on him solely through his communication with his daughter-in-law Parvati (Tillotama Shome). His bonding with his elder granddaughter keeps him going, as does the time that he spends with a buffalo named Annapurna (provider of food), his constant companion. Hedu's peregrinations take him every day to the same dusty, barren spot from where he has a vantage view of the route that the adversarial bank collection agent takes to reach the village on his moped.

Kadvi Hawa Movie Review: Sanjay Mishra and Tillotama Shome in a film still.

This man, Gunu, an Odia who has opted to relocate to a place miles away from home solely because of the lure of a "double commission" on every recovery on behalf of his bank, is bent upon forcing the 30-odd defaulting farmers of the village Mahua to pay up so that he can one day make enough money to return to his part of the world and move his family - a widowed mother, wife and two daughters - to a safer place.

Gunu's coastal village, we learn some way into the film, was wiped off the face of the earth by the sea, taking his father along to a watery grave. His distraught mother is left living in hope that her husband will return someday. Gunu's move to the drought-prone Bundelkhand is an act of self-preservation that reeks of extreme duress.

Kadvi Hawa takes several problems in its limited sweep - climate change, extreme weather conditions, the agrarian crisis, farmer suicides and the insensitivity of the banking system - without wavering in its primary focus. It reveals the sheer magnitude of the environmental disasters that stare us in the face through the 'eyes' of a wizened and innately wise man who cannot 'see' but feels and knows the enormity of the challenges ahead as much as through the scalded conscience of a 'heartless' bank employee who pursues his quarries with the dourness of a bloodhound.

On the odd occasion, the film seems to flag a wee bit because the intimate tale of two blighted families has inevitably to be stretched to accommodate the ambitious span of the portrait that the filmmaker wants to present of the havoc that rain can play when there isn't enough of it just as when there is too much of it. Yet, owing to the clarity of the vision that powers the film, Kadvi Hawa hits home with the force of a gale. It is designed to provoke contemplation and action, a mission that it achieves without any serious slips. Watch it because it is an important film that offers an essential takeaway.