Breaking Bad is Aamir Khan's "favourite"

Mumbai:

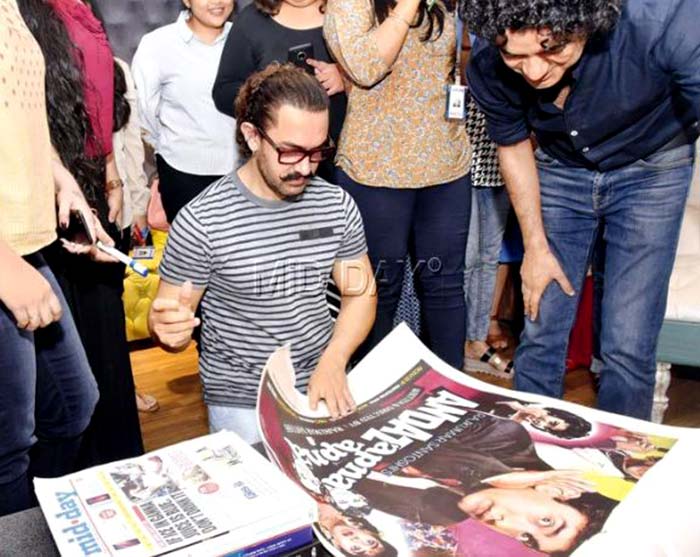

mid-day Exclusive - Aamir Khan kicks off mid-day's unique conversation series, where Mumbai's most popular and sharp creative minds dig deep and decode their art and craft, before a select live audience

Aamir Khan came over, rather under-slept, stressing over the release of his latest film Secret Superstar. He spoke in-depth on the economics and craft of filmmaking. And only two days later, he conquered the box-office yet again with 'Secret Superstar', maintaining an unrivalled cent per cent hit-rate as a Bollywood producer

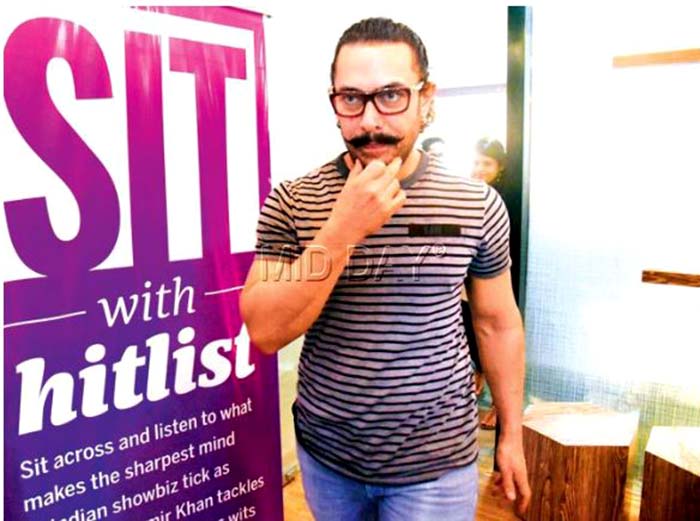

Superstar, filmmaker Aamir Khan kicked off the first edition of Sit with Hitlist - a conversation series with India's top creative minds, before a select audience. We intended to host this freewheeling chat in an auditorium. Date and technical issues did not permit it this time. This was a budget version of 'Sit with Hitlist', held at the mid-day office. But as goes with low-budget ventures, with Aamir in it, we knew the word-of-mouth would ensure mid-day's brand-new property would be a huge hit! It was.

Excerpts from the conversation

Excerpts from the conversation

The big news of 2017 was of course Dangal, and China. Producer Siddharth Roy Kapur's reason for the film's unprecedented success is the Chinese audiences sensed a common Eastern sensibility in the film's father-daughter relationship. Do you agree?

When I visited China and Turkey recently, I realised that their emotional key is very similar to ours. I carefully noticed the reaction that Dangal got in theatres in China. It was the same as for an Indian audience - they were laughing, crying, and clapping at the same points. There was no difference at all.

Is that true for Indians watching Chinese films? I am not sure I get that sensibility the same way.

Well, I saw Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon [2000], and loved it. I was clapping and whistling throughout. I didn't come with any pre-conceived notions. I love Jackie Chan movies. I was in college, when I first saw Police Story [1985] - the action was unbelievable. And it's so humorous. I have connected with these films.

Another theory is that the way the kids get treated in Dangal, and how the father is determined to turn them into champions, is similar to China - except the father is the communist state, attempting to turn them into Olympic gold-medalists from a young age. Do you see a connection?

I never thought of it like that. I've read reactions from Chinese audiences. They apparently watched the film, and desperately wanted to talk to their parents, right after. It is a personal, human connect.

Your personal global reach as an actor really began, thanks to the Internet. Is that right?

My assumption is that it happened with 3 Idiots [2009], which became a huge hit on the Internet. Raju [Hirani] and Vinod [Chopra] got to know about it. Someone from China contacted us, and we released the film there a year later, by when most people had already watched it. They started looking for my other films, and now many of them have watched Taare Zameen Par [2007], Lagaan [2001] and Rang De Basanti [2006].

Considering the strong role of Internet, it was a surprise when I read somewhere that you are such a "big screen guy". Would you bypass something like Netflix?

I was talking about myself as a consumer, and not the creator, of content. As an audience, cinema is more important to me - huge screen, Atmos sound, a richer, larger experience, than a laptop. This doesn't mean I wouldn't want to do a Netflix, or TV series, when the quality is equally cinema-like. I have been asked by them [Netflix] to create something. Content for every platform is different. For Netflix, the content cannot be delivered in one session. The narrative needs to be episodic. I would be keen if something like that comes my way. I have watched Breaking Bad. It's my favourite. I like Game Of Thrones and House of Cards.

One of the central themes of your latest release, Secret Superstar, is how Internet can turn you into an overnight star. How do you compare that kind of stardom with yours, at a time when anything can go viral?

Some of the videos which go viral are one-offs, like a cat doing something funny. But then there are talents that people discover on the Internet - it offers great opportunities. The small-town girl in Secret Superstar has no access, but she is full of passion. She doesn't have to break into the limited distribution network anymore.

Back in the '90s when there wasn't so much talk about box-office numbers, how could you tell someone is finally a star?

From the time I was seven, I remember reading Trade Guide, and other box-office journals. We would check out the figures of dad's films, and there would be a circuit-wise break up. Within the industry, the [box-office] knowledge was always there, since cinema has always been around as a business. Today, mainstream media is picking up box-office figures, and that's a choice you're making.

In small towns, for instance, when people didn't know box-office numbers, one way to gauge stardom was if people had begun copying an actor's haircut. True?

There are many yardsticks for measuring how popular a star is. Copying style is one of them. I remember when Mr Bachchan became a huge star, I wanted to get bell-bottoms made like his. For me, it is essentially about how many seats one fills. It means that people love you and your work, and now they want to go and experience it. That's important. We often measure stardom by how big an actor's commercial successes have been. That is a faulty method. PK's or Dangal's business has to do with how great those films and their scripts were. It's incorrect to attribute that to my stardom. My stardom comes into play when I make a bad film that people don't want to watch. They still come because of my name. So if you want to measure an actor's stardom, you should check out how well his flop does.

In that sense, the Khans have dominated Bollywood for over 25 years. My question to you is: Do you remember the first time you met Salman and Shah Rukh?

The first time I met Salman was at Babla's [director Aditya Bhattacharya's] house, who made Raakh [1989]. Incidentally, Salman and I were in the same class for a year in the second standard [at St Anne's, in Pali Hill]. And we didn't know each other then! I was at Babla's house to discuss a short film called Paranoia, where I was the actor, spot-boy, production head, first AD - all rolled into one. We shot that film for a month. I was 15, and this is the first time I ever acted. Salman was cycling around in Carter Road. He knew Babla too. We stood in the balcony and talked. He told me about how he also wanted to become an actor. I thought of him as a sweet chap. Shah Rukh, I remember meeting briefly, when I was shooting with Juhi [Chawla], somewhere on the road. He had begun shooting a film with her [Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman]. Deewana [his debut, 1992] hadn't released yet. He was sweet, and it was a warm meeting.

Clearly nothing momentous. Now one of the reasons 2017 has been considered a sub-par year in Bollywood is because the two top stars' films didn't do well - let alone break records. Do you think the film industry has been relying on the Khans for too long to bail them out every year?

There are other hugely successful stars - Akshay [Kumar], Hrithik [Roshan], Ajay [Devgn].... The three of us [Khans] have been successful for quite a while; it's natural for the trade to bank [on us]. Sometimes films work, sometimes they don't. At one time, Mr Bachchan was huge. None of us will ever see the stardom he has. He once had eight films simultaneously doing really well in theatres. Trade would bank on him for seats and popcorns. Ideally, there should be more stars. But it's a natural process. Becoming a star is an intangible thing. What is it that people connect with me so strongly over? I have absolutely no idea.

Over a conversation in 2011, you'd told us about a bubble in the film industry, referring to studios that paid money assuming the highest possible returns. Effectively in 2016, most studios went bust. Did you predict this?

Who am I to predict? But it's bad business. Say, Dangal has done R385 crore business, and I come with the next film that gets sold at R400 crore, because a studio is willing to pay that much. They assume that my next will be as big or bigger than Dangal, which was huge to begin with. That's not sound business. A studio can't pay on hope. You have to invest on surety. If the lifetime of the last film is Rs 380 crore, then you know that the next will definitely make Rs 200 crore. The upside is then there for everyone to share. This is why I don't load my film with my fee. My model is that I don't charge any money. All the money goes into filmmaking, and fees, of everyone else. And then the first money [coming in] goes towards recovering the P&A [cost of print and advertising]. Eventually if the film tanks, I get zero. That's a risk I am willing to take. I'd rather lose.

And then if the film [Dangal] does R1,300 crore [in China], means you get a good bulk! Sure, and I bring that value to the table. Investors are completely secure. I take a sizeable chunk. When the film does R1,300 crore, first the government takes a certain tax amount, and a major chunk goes to theatre chains, and the exhibition sector. It's the same with India, except in China, there are also rules on how much people from outside the country can take as share [revenues from a film]. It finally boils down to 12.5 per cent, which is still good.

Did you pick up a mansion from 12.5 per cent of Chinese box-office? I am not good with money. I don't do investments and I have very few properties. Basically, my mind doesn't work in that direction. I am not a business savvy person.

You're certainly good at film business, with a 100 per cent track record as producer.

Creatively I don't want to mess with what I want to do. So, say, I want to do a Dhobi Ghat [2011], I'll make sure it's made in R5 crore. For the investor, I know this [amount] will come back, and we'll make a little profit. Films will be profitable if you make them economically viable, and this gives me the freedom to make what I want.

Here's how you get it right each time: budgeting, great script-sense, making sure casting, locations are spot-on. The new thing I've learnt is how much emphasis you give to the audience testing the first-cut of your film. Unknown people repeatedly watch it in focus groups, whose responses eventually determine the final cut/edit. Isn't that losing creative control, almost like filmmaking by public consensus? Odd, no?

No. It's not [by] public consensus. I'm not going around asking people what I should do with my film - and they say cut this or that - and I make the changes. The whole basis of testing a film is that we have a story in mind that we're trying to narrate to you. I just want to make sure that what I'm narrating to you, is coming through. Or are you receiving something else? We become so close to our material that while making a film, we're not able to be objective enough to understand how it's being received.

Can you give concrete examples from your films where there was disconnect between what you were saying, and what was being received?

Let me give you two examples. Take Sarfarosh [1999] first, which was a cop film, about policing. At the test screenings, the consistent response was, "Where's the policing? We don't see any. He [the cop] is constantly listening to ghazals!" We were like, "How's that possible - there's the Khera Naka scene, with the entire action, his leg gets broken, he's in the hospital, where he dives, despite the injury - all those scenes were there." While we were befuddled, we knew this was a problem. So we added three scenes to the film. One, in the beginning, we raid a corrupt cop in the tribal belt of Maharashtra, where ACP Rathore [his character] goes through the phonebook, to get whereabouts of Sultan, which he gets after delivering a tight slap to the corrupt cop. Again, while searching for Sultan, we reach his mother's house, where I stop my colleagues from being rough with her. The third scene was about a raid, where we caught two guys, who we interrogated, but we were getting nothing out of them. This is when I fire at one of the guys, just so the bullet misses him. He spills the beans.

Wasn't that guy Nawazuddin Siddiqui [in a split second role, much before he became popular]?

That was Nawaz, which I didn't know! When I was working on Talaash [2012] with Nawaz, is when he told me, "Sir, I've already worked with you!" "Kab?" "Sarfarosh mein. Mein wahi tha!" (laughs). So, after inserting those scenes, the problem [over showing policing in the picture] that we were constantly facing, disappeared overnight. Suddenly the film changed.

Another example?

Now the whole thought behind Taare Zameen Par was that one has to be inclusive. Every child has a problem, and you can't segregate them from other kids. What we were arguing for is that special schools should actually not be necessary. All kids should study in the same school. The reaction we would get is: "So, you're saying, Ishan is a special child, so he should study in a special school!" And we were clearly saying the opposite. As were all our lines. We realised there's some miscommunication here, and for the life of me, I couldn't understand why. Now if you remember, the film's title track is shot in a school for special children, where I teach. The school's annual day is going on. The kids are dancing in slow-motion, parents are hugging their kids, I've got tears in my eyes. This is when the song begins. From my face, the screen dissolves to Ishan's face, sitting all alone, lonely and low, in a [regular] boarding school. His parents can't come to meet him, because his brother has a tennis match. We then cut to the brother playing tennis, while his father is upset etc. A friend of mine, Amin Hajee, who played the mute in Lagaan, told me he thinks the problem is in the song: "You're looking at children getting so much love in the special school, and the image dissolves to Ishan alone. It seems you're saying he should be here, and not in a regular school." First I didn't agree with him, because that's not what I was trying to communicate. But, heck, let me try. So instead of dissolving from my face to Ishan's, we cut to the brother, who's not playing tennis well, and then brought in Ishan. We literally changed one thing over 30 seconds. That problem got solved. Nobody made the same point [about the film's intention] anymore. Now with dissolving my face with Ishan's, I wanted to communicate, sub-consciously, that he [Nikumbh, the teacher] actually sees himself in Ishan [he went through the same problems as a kid dealing with Dyslexia]. But I was failing in communicating that anyway. And I've been doing test screenings right since QSQT [Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, 1989].

Showing the first cut to regular junta, from your first major film onwards?

Yes. Some of the reactions make sense, some don't. Many of which I already have answers to, since the film still has to go through post-production. Again, I'll give you a broad example. Often people say that from a particular point, a film becomes very boring: "The moment the song comes in second half, the film dips." Now most people will feel that they should cut the song. But that won't be the solution. You're feeling the weight over here [in the film's timeline], but the reason for that is somewhere earlier [in the film]. There's something wrong in your structure. You need to figure that out. It's like going to a doctor and telling him your symptoms. Can he treat that? No. He can treat your problem. Likewise, there is a dip in the second half, but the problem is somewhere in the first half, you need to treat that - either you haven't built up the plot properly, or the sub-plot is too weak. You need to understand where the correction lies. So it's not filmmaking by consensus. With Raja Hindustani [1996], we had a very bad reaction [from test audiences]. Dharmesh [Darshan] was like, "Oh God, we're finished!" I told him, according to me, you shouldn't change a single thing about the film. So it's a science: you have to know what to take, or correct.

But who did you show Raja Hindustani to? Can't be a Malabar Hill audience, they'll reject it anyway, it's too massy and hardcore.

Well, we showed it to a hardcore Hindi heartland audience. There was a wedding happening in Dharmesh's family, so people had come in from Punjab, Allahabad, and other places.

Another thing I learnt about you, from my childhood [guitarist] friend, who spent over 10 days in your Panchgani house, scoring music with Amit Trivedi, is that you're seriously hands-on. How important is it for a Hindi filmmaker to know his music?

I am not formally trained in music, and I am not involved in the music of every film, unless the producer/director invites me to be part of the process. When I was working with Mansoor [Khan] on Jo Jeeta Wahi Sikander or QSQT, I was very closely involved. As I am with the films I produce.

What do you mean by involved, do you make suggestions?

I react to the piece and convey to the composer what I feel. I might act out something to tell him what I want. Sometimes I do get technical. I have basic knowledge to make a few suggestions. In Secret Superstar, for instance, the song Main Kaun Hoon (sings it) was at one point going on falsetto. It wasn't sounding right. I requested Amit to change it. He obliged. We already had another track, Main Nachdi Phira, going into falsetto. We couldn't do it for two important songs.

You've spoken at length here about the science of filmmaking. How do you merge that with art? (Mohar Basu in the audience asks)

Let me fine-tune your question. It's not the science of filmmaking, but mass communication, because filmmaking may choose not to be mass communication, and then it won't follow these laws that you're talking about. You are trying to communicate to a whole mass, so you try and reach the common point among all these people.

But that's not how I begin. While listening to a script, I become the audience. It's like you watching a film. And at that time, I'm just reacting emotionally to it. For example, when I heard the script of Delhi Belly, I was on the floor, laughing. At that time, I'm not thinking of the science. That happens when I start work on the script, with the director and writer, and say, I check: Have we locked our goal early enough? What is the premise of Delhi Belly? 'Shit happens'.

You keep a one-liner, always?

Yes. The premise and what the film is trying to say are important. A film may not be socially relevant, but it has to say something. So yes, do we have a clear enough premise? Do we want to sharpen it? Is my goal locked, well in advance? There are times when the film is going on and on, and you don't know where it is going, so you start losing interest.

Let's look at Lagaan. The premise is, "Rains aren't happening. You can't pay tax

(lagaan). Gora says, "Lagaan maaf kar denge, if you beat us in cricket." My character says, "Sharat manjoor hai." The moment he says that, my goal is locked. Now, as an audience, I know that cricket main harane wale hain. Now, that journey from goal-locking to the goal has to be exciting, difficult, with a lot of obstacles, which makes it even more exciting. At times, the main plot becomes too boring. Are the subplots getting over, before the main plot? Because if that's not the case, I'm not interested; having reached the goal. The end fizzles out. So these are the basic rules of mass communication in entertainment.

You emphasise strongly on emotional connect, is that something you seek in all your films? (Sonil Dedhia in the audience asks) All. When I say emotional connect, I don't mean crying, because that's what people often associate with that word - "Oh matlab rona dhona hai." What I mean is some emotion is being tapped into - it's making you feel thrilled, giving you lots of stress, because suspense is an emotion being tapped into, in a thriller. Or it could be fear, because it's a horror film. So, the film connecting at an emotional level is important to me.

A distinction between art-house and mainstream, according to a filmmaking wit I once interviewed, is that with the latter, the audience knows exactly what's going to happen (they like that), while with the former, they don't. In fact, they don't even know if anything will happen in an art-house film at all.

I feel that in mainstream cinema, you should have a sense of where the film is headed. But at each stage, if you know what is going to happen, then the film becomes too predictable, and doesn't engage you enough. So it's important to surprise the audience.

Final question: Honestly, decode your character Shakti Kumarr in Secret Superstar. He's a sleazoid called Shakti, clearly named after Shakti Kapoor. He talks a lot like Anu Malik and Anil Kapoor, both of whom I saw at your film's private screening. I've taken a lot from various people and built this personality. I've used Anil's style of talking a few times-like in the awards' night scene, where I say, "Awards lete lete thak gaya hoon main." When Anil says bye to you on the phone, for instance, he never says one 'bye'. He goes, "Okay, bye bye bye bye bye bye...". There are some things that stay with me. Jeetuji [Jeetendra] once came to meet my uncle [Nasir Hussain]. I used to be his assistant at the time. And Jeetuji is a fab guy, with a great sense of humour. He told my uncle, "Nasir saab, mujhe double role offer hua hai. Mujhse ek role theek se hota nahin, mujhe do role de rahe hain!" But he used a phrase then, "Dekhte hain. Buck up India!" Now whenever I meet Jeetuji, he says, "Buck up India." He'd ask me, when is your movie releasing? I'd say, December. "Haan, buck up India!" I used that in the film! (laughs).

There's no Anu Malik in it, come on?

Now, don't ask me who all are in it. Okay, there's a little bit of Anu Malik. But I'm not mimicking anybody, because I can't do that.

mid-day exclusive video: Aamir Khan on Sit With Hitlist

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Aamir Khan came over, rather under-slept, stressing over the release of his latest film Secret Superstar. He spoke in-depth on the economics and craft of filmmaking. And only two days later, he conquered the box-office yet again with 'Secret Superstar', maintaining an unrivalled cent per cent hit-rate as a Bollywood producer

Superstar, filmmaker Aamir Khan kicked off the first edition of Sit with Hitlist - a conversation series with India's top creative minds, before a select audience. We intended to host this freewheeling chat in an auditorium. Date and technical issues did not permit it this time. This was a budget version of 'Sit with Hitlist', held at the mid-day office. But as goes with low-budget ventures, with Aamir in it, we knew the word-of-mouth would ensure mid-day's brand-new property would be a huge hit! It was.

Aamir Khan in conversation with HITLIST (courtesy Nimesh Dave, mid-day)

The big news of 2017 was of course Dangal, and China. Producer Siddharth Roy Kapur's reason for the film's unprecedented success is the Chinese audiences sensed a common Eastern sensibility in the film's father-daughter relationship. Do you agree?

When I visited China and Turkey recently, I realised that their emotional key is very similar to ours. I carefully noticed the reaction that Dangal got in theatres in China. It was the same as for an Indian audience - they were laughing, crying, and clapping at the same points. There was no difference at all.

Is that true for Indians watching Chinese films? I am not sure I get that sensibility the same way.

Well, I saw Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon [2000], and loved it. I was clapping and whistling throughout. I didn't come with any pre-conceived notions. I love Jackie Chan movies. I was in college, when I first saw Police Story [1985] - the action was unbelievable. And it's so humorous. I have connected with these films.

Aamir Khan photographed during interview (courtesy Nimesh Dave, mid-day)

Another theory is that the way the kids get treated in Dangal, and how the father is determined to turn them into champions, is similar to China - except the father is the communist state, attempting to turn them into Olympic gold-medalists from a young age. Do you see a connection?

I never thought of it like that. I've read reactions from Chinese audiences. They apparently watched the film, and desperately wanted to talk to their parents, right after. It is a personal, human connect.

Your personal global reach as an actor really began, thanks to the Internet. Is that right?

My assumption is that it happened with 3 Idiots [2009], which became a huge hit on the Internet. Raju [Hirani] and Vinod [Chopra] got to know about it. Someone from China contacted us, and we released the film there a year later, by when most people had already watched it. They started looking for my other films, and now many of them have watched Taare Zameen Par [2007], Lagaan [2001] and Rang De Basanti [2006].

Aamir Khan photographed during interview (courtesy Nimesh Dave, mid-day)

Considering the strong role of Internet, it was a surprise when I read somewhere that you are such a "big screen guy". Would you bypass something like Netflix?

I was talking about myself as a consumer, and not the creator, of content. As an audience, cinema is more important to me - huge screen, Atmos sound, a richer, larger experience, than a laptop. This doesn't mean I wouldn't want to do a Netflix, or TV series, when the quality is equally cinema-like. I have been asked by them [Netflix] to create something. Content for every platform is different. For Netflix, the content cannot be delivered in one session. The narrative needs to be episodic. I would be keen if something like that comes my way. I have watched Breaking Bad. It's my favourite. I like Game Of Thrones and House of Cards.

One of the central themes of your latest release, Secret Superstar, is how Internet can turn you into an overnight star. How do you compare that kind of stardom with yours, at a time when anything can go viral?

Some of the videos which go viral are one-offs, like a cat doing something funny. But then there are talents that people discover on the Internet - it offers great opportunities. The small-town girl in Secret Superstar has no access, but she is full of passion. She doesn't have to break into the limited distribution network anymore.

Aamir Khan photographed during interview (courtesy Nimesh Dave, mid-day)

Back in the '90s when there wasn't so much talk about box-office numbers, how could you tell someone is finally a star?

From the time I was seven, I remember reading Trade Guide, and other box-office journals. We would check out the figures of dad's films, and there would be a circuit-wise break up. Within the industry, the [box-office] knowledge was always there, since cinema has always been around as a business. Today, mainstream media is picking up box-office figures, and that's a choice you're making.

In small towns, for instance, when people didn't know box-office numbers, one way to gauge stardom was if people had begun copying an actor's haircut. True?

There are many yardsticks for measuring how popular a star is. Copying style is one of them. I remember when Mr Bachchan became a huge star, I wanted to get bell-bottoms made like his. For me, it is essentially about how many seats one fills. It means that people love you and your work, and now they want to go and experience it. That's important. We often measure stardom by how big an actor's commercial successes have been. That is a faulty method. PK's or Dangal's business has to do with how great those films and their scripts were. It's incorrect to attribute that to my stardom. My stardom comes into play when I make a bad film that people don't want to watch. They still come because of my name. So if you want to measure an actor's stardom, you should check out how well his flop does.

Aamir Khan photographed during interview (courtesy Nimesh Dave, mid-day)

In that sense, the Khans have dominated Bollywood for over 25 years. My question to you is: Do you remember the first time you met Salman and Shah Rukh?

The first time I met Salman was at Babla's [director Aditya Bhattacharya's] house, who made Raakh [1989]. Incidentally, Salman and I were in the same class for a year in the second standard [at St Anne's, in Pali Hill]. And we didn't know each other then! I was at Babla's house to discuss a short film called Paranoia, where I was the actor, spot-boy, production head, first AD - all rolled into one. We shot that film for a month. I was 15, and this is the first time I ever acted. Salman was cycling around in Carter Road. He knew Babla too. We stood in the balcony and talked. He told me about how he also wanted to become an actor. I thought of him as a sweet chap. Shah Rukh, I remember meeting briefly, when I was shooting with Juhi [Chawla], somewhere on the road. He had begun shooting a film with her [Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman]. Deewana [his debut, 1992] hadn't released yet. He was sweet, and it was a warm meeting.

Clearly nothing momentous. Now one of the reasons 2017 has been considered a sub-par year in Bollywood is because the two top stars' films didn't do well - let alone break records. Do you think the film industry has been relying on the Khans for too long to bail them out every year?

There are other hugely successful stars - Akshay [Kumar], Hrithik [Roshan], Ajay [Devgn].... The three of us [Khans] have been successful for quite a while; it's natural for the trade to bank [on us]. Sometimes films work, sometimes they don't. At one time, Mr Bachchan was huge. None of us will ever see the stardom he has. He once had eight films simultaneously doing really well in theatres. Trade would bank on him for seats and popcorns. Ideally, there should be more stars. But it's a natural process. Becoming a star is an intangible thing. What is it that people connect with me so strongly over? I have absolutely no idea.

Aamir Khan photographed during interview (courtesy Nimesh Dave, mid-day)

Over a conversation in 2011, you'd told us about a bubble in the film industry, referring to studios that paid money assuming the highest possible returns. Effectively in 2016, most studios went bust. Did you predict this?

Who am I to predict? But it's bad business. Say, Dangal has done R385 crore business, and I come with the next film that gets sold at R400 crore, because a studio is willing to pay that much. They assume that my next will be as big or bigger than Dangal, which was huge to begin with. That's not sound business. A studio can't pay on hope. You have to invest on surety. If the lifetime of the last film is Rs 380 crore, then you know that the next will definitely make Rs 200 crore. The upside is then there for everyone to share. This is why I don't load my film with my fee. My model is that I don't charge any money. All the money goes into filmmaking, and fees, of everyone else. And then the first money [coming in] goes towards recovering the P&A [cost of print and advertising]. Eventually if the film tanks, I get zero. That's a risk I am willing to take. I'd rather lose.

And then if the film [Dangal] does R1,300 crore [in China], means you get a good bulk! Sure, and I bring that value to the table. Investors are completely secure. I take a sizeable chunk. When the film does R1,300 crore, first the government takes a certain tax amount, and a major chunk goes to theatre chains, and the exhibition sector. It's the same with India, except in China, there are also rules on how much people from outside the country can take as share [revenues from a film]. It finally boils down to 12.5 per cent, which is still good.

Did you pick up a mansion from 12.5 per cent of Chinese box-office? I am not good with money. I don't do investments and I have very few properties. Basically, my mind doesn't work in that direction. I am not a business savvy person.

You're certainly good at film business, with a 100 per cent track record as producer.

Creatively I don't want to mess with what I want to do. So, say, I want to do a Dhobi Ghat [2011], I'll make sure it's made in R5 crore. For the investor, I know this [amount] will come back, and we'll make a little profit. Films will be profitable if you make them economically viable, and this gives me the freedom to make what I want.

Here's how you get it right each time: budgeting, great script-sense, making sure casting, locations are spot-on. The new thing I've learnt is how much emphasis you give to the audience testing the first-cut of your film. Unknown people repeatedly watch it in focus groups, whose responses eventually determine the final cut/edit. Isn't that losing creative control, almost like filmmaking by public consensus? Odd, no?

No. It's not [by] public consensus. I'm not going around asking people what I should do with my film - and they say cut this or that - and I make the changes. The whole basis of testing a film is that we have a story in mind that we're trying to narrate to you. I just want to make sure that what I'm narrating to you, is coming through. Or are you receiving something else? We become so close to our material that while making a film, we're not able to be objective enough to understand how it's being received.

Can you give concrete examples from your films where there was disconnect between what you were saying, and what was being received?

Let me give you two examples. Take Sarfarosh [1999] first, which was a cop film, about policing. At the test screenings, the consistent response was, "Where's the policing? We don't see any. He [the cop] is constantly listening to ghazals!" We were like, "How's that possible - there's the Khera Naka scene, with the entire action, his leg gets broken, he's in the hospital, where he dives, despite the injury - all those scenes were there." While we were befuddled, we knew this was a problem. So we added three scenes to the film. One, in the beginning, we raid a corrupt cop in the tribal belt of Maharashtra, where ACP Rathore [his character] goes through the phonebook, to get whereabouts of Sultan, which he gets after delivering a tight slap to the corrupt cop. Again, while searching for Sultan, we reach his mother's house, where I stop my colleagues from being rough with her. The third scene was about a raid, where we caught two guys, who we interrogated, but we were getting nothing out of them. This is when I fire at one of the guys, just so the bullet misses him. He spills the beans.

Wasn't that guy Nawazuddin Siddiqui [in a split second role, much before he became popular]?

That was Nawaz, which I didn't know! When I was working on Talaash [2012] with Nawaz, is when he told me, "Sir, I've already worked with you!" "Kab?" "Sarfarosh mein. Mein wahi tha!" (laughs). So, after inserting those scenes, the problem [over showing policing in the picture] that we were constantly facing, disappeared overnight. Suddenly the film changed.

Another example?

Now the whole thought behind Taare Zameen Par was that one has to be inclusive. Every child has a problem, and you can't segregate them from other kids. What we were arguing for is that special schools should actually not be necessary. All kids should study in the same school. The reaction we would get is: "So, you're saying, Ishan is a special child, so he should study in a special school!" And we were clearly saying the opposite. As were all our lines. We realised there's some miscommunication here, and for the life of me, I couldn't understand why. Now if you remember, the film's title track is shot in a school for special children, where I teach. The school's annual day is going on. The kids are dancing in slow-motion, parents are hugging their kids, I've got tears in my eyes. This is when the song begins. From my face, the screen dissolves to Ishan's face, sitting all alone, lonely and low, in a [regular] boarding school. His parents can't come to meet him, because his brother has a tennis match. We then cut to the brother playing tennis, while his father is upset etc. A friend of mine, Amin Hajee, who played the mute in Lagaan, told me he thinks the problem is in the song: "You're looking at children getting so much love in the special school, and the image dissolves to Ishan alone. It seems you're saying he should be here, and not in a regular school." First I didn't agree with him, because that's not what I was trying to communicate. But, heck, let me try. So instead of dissolving from my face to Ishan's, we cut to the brother, who's not playing tennis well, and then brought in Ishan. We literally changed one thing over 30 seconds. That problem got solved. Nobody made the same point [about the film's intention] anymore. Now with dissolving my face with Ishan's, I wanted to communicate, sub-consciously, that he [Nikumbh, the teacher] actually sees himself in Ishan [he went through the same problems as a kid dealing with Dyslexia]. But I was failing in communicating that anyway. And I've been doing test screenings right since QSQT [Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, 1989].

Showing the first cut to regular junta, from your first major film onwards?

Yes. Some of the reactions make sense, some don't. Many of which I already have answers to, since the film still has to go through post-production. Again, I'll give you a broad example. Often people say that from a particular point, a film becomes very boring: "The moment the song comes in second half, the film dips." Now most people will feel that they should cut the song. But that won't be the solution. You're feeling the weight over here [in the film's timeline], but the reason for that is somewhere earlier [in the film]. There's something wrong in your structure. You need to figure that out. It's like going to a doctor and telling him your symptoms. Can he treat that? No. He can treat your problem. Likewise, there is a dip in the second half, but the problem is somewhere in the first half, you need to treat that - either you haven't built up the plot properly, or the sub-plot is too weak. You need to understand where the correction lies. So it's not filmmaking by consensus. With Raja Hindustani [1996], we had a very bad reaction [from test audiences]. Dharmesh [Darshan] was like, "Oh God, we're finished!" I told him, according to me, you shouldn't change a single thing about the film. So it's a science: you have to know what to take, or correct.

But who did you show Raja Hindustani to? Can't be a Malabar Hill audience, they'll reject it anyway, it's too massy and hardcore.

Well, we showed it to a hardcore Hindi heartland audience. There was a wedding happening in Dharmesh's family, so people had come in from Punjab, Allahabad, and other places.

Another thing I learnt about you, from my childhood [guitarist] friend, who spent over 10 days in your Panchgani house, scoring music with Amit Trivedi, is that you're seriously hands-on. How important is it for a Hindi filmmaker to know his music?

I am not formally trained in music, and I am not involved in the music of every film, unless the producer/director invites me to be part of the process. When I was working with Mansoor [Khan] on Jo Jeeta Wahi Sikander or QSQT, I was very closely involved. As I am with the films I produce.

What do you mean by involved, do you make suggestions?

I react to the piece and convey to the composer what I feel. I might act out something to tell him what I want. Sometimes I do get technical. I have basic knowledge to make a few suggestions. In Secret Superstar, for instance, the song Main Kaun Hoon (sings it) was at one point going on falsetto. It wasn't sounding right. I requested Amit to change it. He obliged. We already had another track, Main Nachdi Phira, going into falsetto. We couldn't do it for two important songs.

You've spoken at length here about the science of filmmaking. How do you merge that with art? (Mohar Basu in the audience asks)

Let me fine-tune your question. It's not the science of filmmaking, but mass communication, because filmmaking may choose not to be mass communication, and then it won't follow these laws that you're talking about. You are trying to communicate to a whole mass, so you try and reach the common point among all these people.

But that's not how I begin. While listening to a script, I become the audience. It's like you watching a film. And at that time, I'm just reacting emotionally to it. For example, when I heard the script of Delhi Belly, I was on the floor, laughing. At that time, I'm not thinking of the science. That happens when I start work on the script, with the director and writer, and say, I check: Have we locked our goal early enough? What is the premise of Delhi Belly? 'Shit happens'.

You keep a one-liner, always?

Yes. The premise and what the film is trying to say are important. A film may not be socially relevant, but it has to say something. So yes, do we have a clear enough premise? Do we want to sharpen it? Is my goal locked, well in advance? There are times when the film is going on and on, and you don't know where it is going, so you start losing interest.

Let's look at Lagaan. The premise is, "Rains aren't happening. You can't pay tax

(lagaan). Gora says, "Lagaan maaf kar denge, if you beat us in cricket." My character says, "Sharat manjoor hai." The moment he says that, my goal is locked. Now, as an audience, I know that cricket main harane wale hain. Now, that journey from goal-locking to the goal has to be exciting, difficult, with a lot of obstacles, which makes it even more exciting. At times, the main plot becomes too boring. Are the subplots getting over, before the main plot? Because if that's not the case, I'm not interested; having reached the goal. The end fizzles out. So these are the basic rules of mass communication in entertainment.

You emphasise strongly on emotional connect, is that something you seek in all your films? (Sonil Dedhia in the audience asks) All. When I say emotional connect, I don't mean crying, because that's what people often associate with that word - "Oh matlab rona dhona hai." What I mean is some emotion is being tapped into - it's making you feel thrilled, giving you lots of stress, because suspense is an emotion being tapped into, in a thriller. Or it could be fear, because it's a horror film. So, the film connecting at an emotional level is important to me.

A distinction between art-house and mainstream, according to a filmmaking wit I once interviewed, is that with the latter, the audience knows exactly what's going to happen (they like that), while with the former, they don't. In fact, they don't even know if anything will happen in an art-house film at all.

I feel that in mainstream cinema, you should have a sense of where the film is headed. But at each stage, if you know what is going to happen, then the film becomes too predictable, and doesn't engage you enough. So it's important to surprise the audience.

Final question: Honestly, decode your character Shakti Kumarr in Secret Superstar. He's a sleazoid called Shakti, clearly named after Shakti Kapoor. He talks a lot like Anu Malik and Anil Kapoor, both of whom I saw at your film's private screening. I've taken a lot from various people and built this personality. I've used Anil's style of talking a few times-like in the awards' night scene, where I say, "Awards lete lete thak gaya hoon main." When Anil says bye to you on the phone, for instance, he never says one 'bye'. He goes, "Okay, bye bye bye bye bye bye...". There are some things that stay with me. Jeetuji [Jeetendra] once came to meet my uncle [Nasir Hussain]. I used to be his assistant at the time. And Jeetuji is a fab guy, with a great sense of humour. He told my uncle, "Nasir saab, mujhe double role offer hua hai. Mujhse ek role theek se hota nahin, mujhe do role de rahe hain!" But he used a phrase then, "Dekhte hain. Buck up India!" Now whenever I meet Jeetuji, he says, "Buck up India." He'd ask me, when is your movie releasing? I'd say, December. "Haan, buck up India!" I used that in the film! (laughs).

There's no Anu Malik in it, come on?

Now, don't ask me who all are in it. Okay, there's a little bit of Anu Malik. But I'm not mimicking anybody, because I can't do that.

mid-day exclusive video: Aamir Khan on Sit With Hitlist

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)