PM Modi has limited time and resources to implement the ambitious plan before 2019 elections (Reuters)

Quick Take

Summary is AI generated, newsroom reviewed.

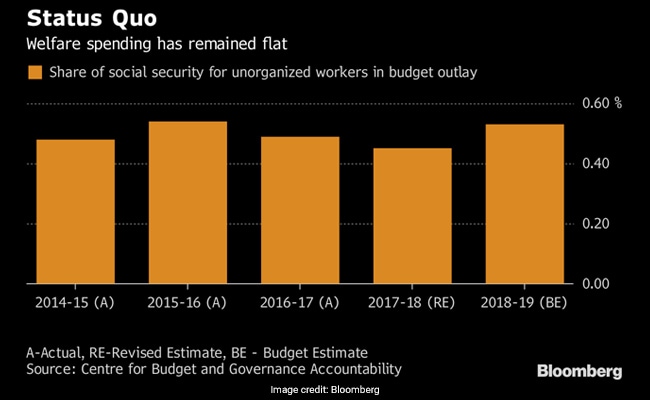

New scheme likely to add pressure on India's widening fiscal deficit

Workers in informal employment will be covered in newly drafted bill

New plan will be one of India's largest mass benefit programmes

PM Modi aims to initially provide three programs - old age pension, life insurance and maternity benefits, while leaving out unemployment, child support and other benefits - to most working citizens, government officials said, asking not to be identified as discussions are private.

While it could translate into significant political gains to offset the challenges he faces in the lead up to the national poll, it is likely to add pressure on India's fiscal deficit, already one of the widest in Asia.

The government has drafted a bill to extend benefits to all workers, including those in informal employment, by merging and simplifying 15 central labor laws into one. It plans to present the bill in July in the upcoming session of parliament, Labour Minister Santosh Gangwar told Bloomberg News, while remaining non-committal on a full-fledged roll-out before the national poll.

The government will face difficulties to provide benefits from its current $376 billion budget

The government plans to pilot the project in six districts in the months leading up to the national elections due in May next year, the officials said.

"Nobody can deny the importance of social security for the country's working class and it is overdue," said Satish Misra, a political analyst at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi. "But the timing suggests it's political in nature and Modi wants to push it in a hurry so that in election campaign he can claim it's a game changer for the poor."

It will be a challenge to make the system sustainable, and difficult for the government to provide benefits from its current $376 billion budget. It intends to limit the initial scope to maternity, pension, and death or disability benefits, leaving out unemployment and child support, the officials said.

The move is expected to have a dual impact on the economy. Higher social spending would add to fiscal stress and limit the scope for infrastructure development. But by giving benefits mostly to informal workers who contribute to about half of the country's GDP, it would enhance the quality of life and raise productivity.

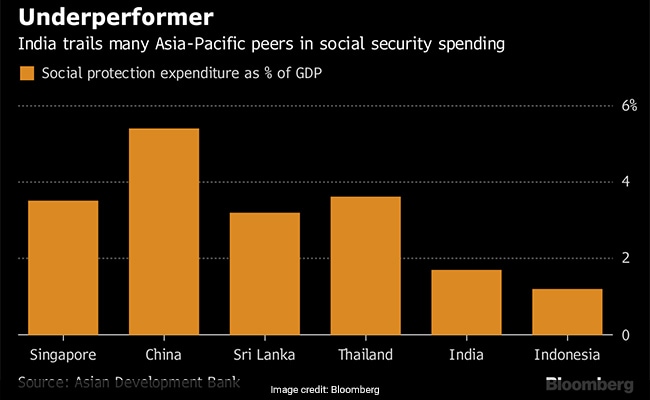

India still spends less than 2 percent of its GDP on social security

While the comprehensive plan is for all workers, the government is concerned about the bottom half of the country's workforce. The rest are expected to make their own contributions, either fully or partially.

It will help reduce poverty in a country that's home to a third of the world's poor and still spends less than 2 percent of its GDP on social security. More than 90 percent of India's workforce is in informal employment and without any social protection.

While the comprehensive plan is for all workers, the government is concerned about the bottom half of the country's workforce

The panel will recommend benefits are paid at a rate that's above the poverty line -- 27 rupees (.40 cents) a day in rural areas and 33 rupees in urban areas, said Mr Mehrotra, who has been asked by the government to calculate the cost of the program.

"In 22 years, India will be an ageing society like China. If it doesn't start working on social security today, who will pay for those old people?" said Mr Mehtrotra.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world