The report lists remedies to ensure the purchase of weapons can realistically be expected.

New Delhi:

India's weapons-buying is frequently crippled by "multiple and diffused structures with no single point accountability, multiple decision-heads, duplication of processes, delayed comments, delayed execution, no real-time monitoring, no project-based approach and a tendency to fault-find rather than to facilitate," assesses a damning Defence Ministry report exclusively accessed by NDTV.

As a result of these flaws, the government's flagship "Make in India" initiative for the defence sector, launched in 2014, "continues to languish at the altar of procedural delays and has failed to demonstrate its true potential."

The 27-point internal report prepared late last year by Minister of State for Defence Subhash Bhamre is a stinging indictment of the way the Defence Ministry functions.

Of 144 deals in the last three financial years, "only 8%-10% fructified within the stipulated time period," it says.

Significantly, a chart identifies how each step of the nine-stage process of ordering weaponry sees enormous delays.

From the stage of Request for Proposal (RFP), when the government formally reaches out to arms manufacturers to submit their sales pitch, to the deal-closing clearance given by the Competent Financial Authority, the delays are a whopping 2.6 times to 15.4 times the deadline.

From the stage of Request for Proposal (RFP), when the government formally reaches out to arms manufacturers to submit their sales pitch, to the deal-closing clearance given by the Competent Financial Authority, the delays are a whopping 2.6 times to 15.4 times the deadline.

The problems begin at the level of the headquarters of the individual armed forces, when the demand for new purchases is first raised.

Pointing at a "lack of synergy between the three services", the report says that the Army, Air Force, Navy and Coast Guard do not work as a system, which "puts greater strain on the limited defence budget and as a result, we are unable to meet the critical capability requirements."

What's more, different departments of the ministry "appear to be working in independent silos" driven by their interpretation of policy and procedures.

Later, once a weapons purchase enters the Request for Proposal (RFP) stage, the average time taken to clear files is 120 weeks - six times more than rules laid down by the ministry in 2016. "The fastest RFP clearance was accorded in 17 weeks while the slowest took a monumental 422 weeks (over eight years)," the report noted.

The report points out that the Armed Forces, as eventual users of the weapon systems, "continue to view the Acquisition Wing (of the Defence Ministry) as an obstacle rather than a facilitator". So there needs to be a "tectonic change in mindset of the ministry officials and the need of the hour is assigning responsibility and accountability."

At the level of Trials and Evaluation conducted by the Armed forces, "the average time taken is 89 weeks, which is three times more than authorised." The armed forces are a part of the problem here, as they list "ambiguous trial directives, leaving scope for varied interpretation."

Dr Bhamre says in his report that the Technical Oversight Committee (TOC) stage needs to be done away with altogether. "I am not sure whether any TOC has brought up any relevant issue, and is assessed to be yet another delay in the procurement procedure."

The Cost Negotiation Committee (CNC) stage sees delays "about 10 times more than that allowed" because of the inability of the Defence Ministry to benchmark costs with global standards "especially where an item is being procured for the first time or involved Transfer of Technology."

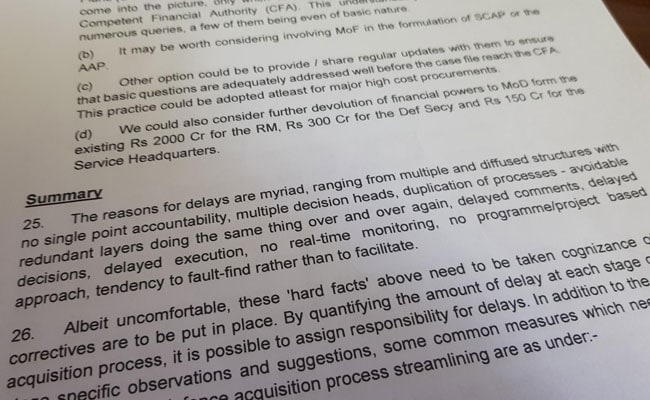

Shockingly, even if a weapons system actually makes its way through this bureaucratic quagmire, an acquisition can be shot down when the file reaches the Finance Ministry or the Cabinet Committee of Security since "currently, the MoF or CCS is not aware" of the defence ministry's plans and needs.

The report also flags the "raining of numerous queries, a few of them even of a basic nature."

In other words, the Finance Ministry doesn't seem to have any idea of what to do with a complex agreement once it is presented by the Defence Ministry for financial clearance so that a contract can be signed.

Given the fairly hopeless bureaucratic jumble within the government, the report lists a series of remedies to de-clutter the process, revolving around "accountability" and "ownership", to ensure the purchase of weapons can realistically be expected.

But ridding the government of this debilitating red-tape will not be easy.

Just last week, 17 years after the Air Force stated a requirement for 126 modern fighter jets, the Defence Ministry shot down a process to build more than 100 of these jets in India under "Make in India".

The two main firms competing for this order were America's Lockheed Martin, which offered its F-16 Block 70IN fighter, and Sweden's SAAB, which was competing with its Gripen E/F jet.

Now, the government wants the Indian Air Force to broaden the scope of this contract to also include multi-engine fighters, a decision taken soon after the controversy over the Rafale fighter deal where the government was accused by the opposition of not being transparent in its handling of the contract with the French government.

Now, the government wants the Indian Air Force to broaden the scope of this contract to also include multi-engine fighters, a decision taken soon after the controversy over the Rafale fighter deal where the government was accused by the opposition of not being transparent in its handling of the contract with the French government.

For the Air Force, which is seeing its squadron strength drastically fall because older jets need to be retired, there is a strange sense of deja-vu about it all.

In 2001, the IAF projected its requirement under the Medium Range Combat Aircraft (MRCA) deal for single-engine jet fighters. The scope of the deal changed dramatically when the government said that they wanted to include twin-engine fighters in the IAF's fighter-fly off. Since twin-engine jets are heavier and more capable, "MRCA" warped into "MMRCA," or Medium Multirole Combat Aircraft, a deal which was ultimately scrapped altogether in 2016, after an incredible 15-year process. Finally, in 2016, realising that the Indian Air Force was desperate, the government agreed, controversially, to buy 36 Rafale fighters from France in an off-the-shelf purchase worth more than Rs. 58,000 crores.

But there was still a semblance of hope because two years ago, the government had also promised to open a brand new process for single-engine fighters, which would be acquired in significantly larger numbers, made in India and bought at considerably lower per-unit costs.

With the decision to scrap this deal, and given the ministry's own track record, it seems clear that the Indian Air Force will not be inducting any new type of fighter for several years to come other than the indigenous Tejas, which is smaller and less capable than the variants of the F-16 or Gripen the Air Force was looking to acquire.

In December, NDTV emailed a set of questions on the report on Defence Procurement to the Defence Ministry's spokesperson, who acknowledged them but offered no answers. Separate reminders through phone messages were also acknowledged but, again, no answers were provided.

As a result of these flaws, the government's flagship "Make in India" initiative for the defence sector, launched in 2014, "continues to languish at the altar of procedural delays and has failed to demonstrate its true potential."

The 27-point internal report prepared late last year by Minister of State for Defence Subhash Bhamre is a stinging indictment of the way the Defence Ministry functions.

Of 144 deals in the last three financial years, "only 8%-10% fructified within the stipulated time period," it says.

Significantly, a chart identifies how each step of the nine-stage process of ordering weaponry sees enormous delays.

The Defence Ministry says the Army, Air Force, Navy and Coast Guard do not work as a system.

The problems begin at the level of the headquarters of the individual armed forces, when the demand for new purchases is first raised.

Pointing at a "lack of synergy between the three services", the report says that the Army, Air Force, Navy and Coast Guard do not work as a system, which "puts greater strain on the limited defence budget and as a result, we are unable to meet the critical capability requirements."

What's more, different departments of the ministry "appear to be working in independent silos" driven by their interpretation of policy and procedures.

Later, once a weapons purchase enters the Request for Proposal (RFP) stage, the average time taken to clear files is 120 weeks - six times more than rules laid down by the ministry in 2016. "The fastest RFP clearance was accorded in 17 weeks while the slowest took a monumental 422 weeks (over eight years)," the report noted.

The report points out that the Armed Forces, as eventual users of the weapon systems, "continue to view the Acquisition Wing (of the Defence Ministry) as an obstacle rather than a facilitator". So there needs to be a "tectonic change in mindset of the ministry officials and the need of the hour is assigning responsibility and accountability."

At the level of Trials and Evaluation conducted by the Armed forces, "the average time taken is 89 weeks, which is three times more than authorised." The armed forces are a part of the problem here, as they list "ambiguous trial directives, leaving scope for varied interpretation."

Dr Bhamre says in his report that the Technical Oversight Committee (TOC) stage needs to be done away with altogether. "I am not sure whether any TOC has brought up any relevant issue, and is assessed to be yet another delay in the procurement procedure."

The Cost Negotiation Committee (CNC) stage sees delays "about 10 times more than that allowed" because of the inability of the Defence Ministry to benchmark costs with global standards "especially where an item is being procured for the first time or involved Transfer of Technology."

Shockingly, even if a weapons system actually makes its way through this bureaucratic quagmire, an acquisition can be shot down when the file reaches the Finance Ministry or the Cabinet Committee of Security since "currently, the MoF or CCS is not aware" of the defence ministry's plans and needs.

The report also flags the "raining of numerous queries, a few of them even of a basic nature."

In other words, the Finance Ministry doesn't seem to have any idea of what to do with a complex agreement once it is presented by the Defence Ministry for financial clearance so that a contract can be signed.

Given the fairly hopeless bureaucratic jumble within the government, the report lists a series of remedies to de-clutter the process, revolving around "accountability" and "ownership", to ensure the purchase of weapons can realistically be expected.

But ridding the government of this debilitating red-tape will not be easy.

Just last week, 17 years after the Air Force stated a requirement for 126 modern fighter jets, the Defence Ministry shot down a process to build more than 100 of these jets in India under "Make in India".

The two main firms competing for this order were America's Lockheed Martin, which offered its F-16 Block 70IN fighter, and Sweden's SAAB, which was competing with its Gripen E/F jet.

America's Lockheed Martin had offered to build its F-16 Block 70IN fighter in India.

For the Air Force, which is seeing its squadron strength drastically fall because older jets need to be retired, there is a strange sense of deja-vu about it all.

In 2001, the IAF projected its requirement under the Medium Range Combat Aircraft (MRCA) deal for single-engine jet fighters. The scope of the deal changed dramatically when the government said that they wanted to include twin-engine fighters in the IAF's fighter-fly off. Since twin-engine jets are heavier and more capable, "MRCA" warped into "MMRCA," or Medium Multirole Combat Aircraft, a deal which was ultimately scrapped altogether in 2016, after an incredible 15-year process. Finally, in 2016, realising that the Indian Air Force was desperate, the government agreed, controversially, to buy 36 Rafale fighters from France in an off-the-shelf purchase worth more than Rs. 58,000 crores.

But there was still a semblance of hope because two years ago, the government had also promised to open a brand new process for single-engine fighters, which would be acquired in significantly larger numbers, made in India and bought at considerably lower per-unit costs.

With the decision to scrap this deal, and given the ministry's own track record, it seems clear that the Indian Air Force will not be inducting any new type of fighter for several years to come other than the indigenous Tejas, which is smaller and less capable than the variants of the F-16 or Gripen the Air Force was looking to acquire.

In December, NDTV emailed a set of questions on the report on Defence Procurement to the Defence Ministry's spokesperson, who acknowledged them but offered no answers. Separate reminders through phone messages were also acknowledged but, again, no answers were provided.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world