The priest's request is antithetical to the plan laid out for the Patidars by Hardik Patel, the feisty 24-year-old from whom the community has been taking its cue since 2015, when he coalesced the diminishing prosperity and dissatisfaction of his once-wealthy caste into a powerful agitation against the BJP, who, he says, has betrayed the Patidars despite their long-time support.

Through social media, massive rallies in cities like Surat and Mehsana, and despite 9 months in jail after which he was exiled from Gujarat for 6 months, Hardik Patel has made a single point: that his caste must be included in those that benefit from affirmative action policies in Prime Minister Narendra Modi's home state.

Hardik Patel mobilised the Patidar community against the BJP, alleging the Patel youth was excluded from education and job opportunities

Hardik Patel has proven his ability to draw large audiences. To them, he roars, often with a turban on his head though he no longer appears with a sword as he once used to, "Defeat the BJP." He has pledged support to the Congress, though he has neither joined it nor agreed to campaign for the opposition party. Last night, in service of playing hard to get, he was a no-show at a meeting with top Congress leaders in Ahmedabad, choosing instead to send about 10 aides to negotiate what the Congress will offer on reservation to the Patidars.

Hardik Patel has vowed to support the Congress in December's election

And here's how he could do it.

Nearly half of Gujarat's voters are younger than 35 - for the Patidars among them, Hardik Patel is top influencer. They follow him on social media, join his demonstrations when he reaches out to them, and identify with his seize-the-moment politics.

Another group in the community likely to side with him is his own sub-caste of Kadva Patels who are concentrated largely in North Gujarat. A majority of them are small farmers and shopkeepers who see no future in agriculture. They want to be declared an Other Backward Caste or OBC. Gujarat has 146 of these already. Together, they are entitled to 27% of government jobs.

Hardik Patel posing for a selfie with his supporters during a rally in Gujarat

That stand is employed by the Other Backward Castes to claim that a section of Patels want not reservation (which would eat into the share of existing beneficiaries) but an overhaul of a system that has allowed once-weaker castes to become their social equals and occupy top positions in the bureaucracy. OBC leader Alpesh Thakore, who joined the Congress last month, says he finds Hardik Patel "a natural ally" even as he tries to protect OBC turf from being encroached by Patidars.

In evidence of how complex the competition over caste is, another branch of the Lehua Patels from Saurashtra, who control the diamond industry in Surat and have been badly affected by its slump, seem inclined to ditch the BJP. Party leaders are finding it difficult to campaign in several parts of Saurashtra as Patidar dominated villages have banned their entry (Hardik Patel held his first reservation rally in Surat in August 2015 in which nearly 5 lakh Patels participated).

At rallies and roadshows, Hardik Patel has been delivering speeches against the BJP government

The Congress won 22 of the 31 district panchayats and 126 of 230 taluka panchayats. Earlier, the BJP held 30 of 31 district panchayats and 194 of 220 taluka panchayats.

It was around this time that Hardik Patel was accused of sedition, jailed for nine months, and then ordered to spend another six months outside Gujarat before being allowed to re-enter the state in January.

Hardik Patel was arrested in 2016 when his agitation for reservation turned violent

The Supreme Court has set a limit of 50% on reservation. Gujarat already uses 49% of that allowance. Adding another caste will be challenged and defeated in court.

With the Patidars seething, BJP chief Amit Shah compiled his own team in the capital of Gandhinagar to course correct. He started by replacing Chief minister Anandiben Patel (a close confidant of PM Modi) with one of his own men, Vijay Rupani, a political lightweight from the Jain community. But to keep the Patels from being offended by Anandiben's exit, Amit Shah ensured top posts for the two prominent sub-castes of the Patidars. Jitubhai Vaghani, a 46-year-old Leuva Patel from Saurashtra, was appointed state party chief, and Nitin Patel, a Kadva Patel from north Gujarat, the epicentre of Hardik Patel's agitation, became Deputy Chief Minister.

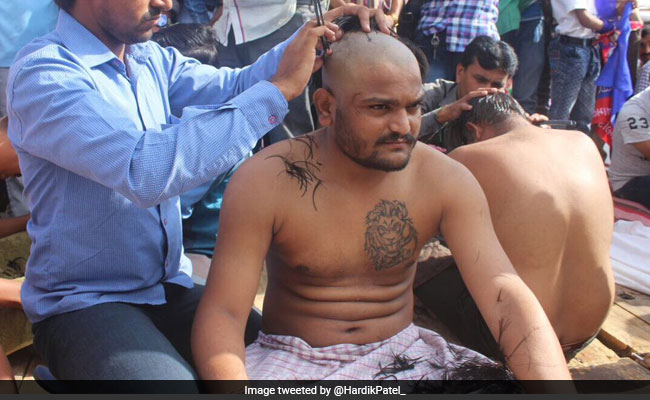

Hardik Patel getting his head shaved as a mark of protest, alleging "atrocities" against his community by the BJP government (May, 2017)

"The large crowds at his rallies are made up almost entirely of Congress workers. Very few Patels are now supporting Hardik, because they know that the Supreme Court's cap on reservations cannot be lifted by him or his agitations. He is misleading the people for personal gains," claims Tejshree Patel the former MLA from Hardik Patel's home town of Viramgam. A trained doctor, Tejshree Patel was with the Congress till August when she resigned along with 14 other Congress MLAs in an attempt to ensure the defeat of senior Congress leader Ahmed Patel in his re-election to the Rajya Sabha. She later joined the BJP. Ahmed Patel won his bid.

Hardik Patel at a farmers' rally in Vadodara, Gujarat

The Congress also knows that any attempt to include the Patels in the list of Gujarat's OBCs will be trashed by court which is why Vice President Rahul Gandhi has refrained from talking about quotas in his campaign speeches, focusing more on the problems caused by the newly launched GST tax and demonetization of high value notes. Over and over, Mr Gandhi drives home the point that these reforms resulted in not just an economic slowdown but also crushed the entrepreneurial spirit of the small-time Gujarati businessman.

Under the circumstances, the best the Congress can hope for is a division of Patel votes, a job which Hardik Patel appears to have embraced. "After 25 years, the time has come for us to throw out the BJP and free our community," he said a fortnight ago to a crowd of thousands at a rally in Saurashtra's Surendranagar town. Hardik asks the people - mainly men age 50 and younger - not to vote for the BJP, "even if the party fields my father Bharat Patel as a candidate." They cheer wildly, but privately admit to being confused about whether to back the Congress.

Hardik Patel has accused the state government of dilly-dallying on the issue of reservation to Patel community

Bhavesh Patel stops short of naming the party that will finally get his vote - reflecting the indecision that his community is struggling with. Socially and politically, the community views itself as a single entity and often raises the slogan of 'P for Patels' to define their solidarity - a unity that Hardik Patel could well unspool.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world