It took 17 years for the Air Force's request to see result in the form of 36 French Rafale fighters

- Dr Subhash Bhambre calls for change in attitude to being time-conscious

- Dr Bhamre's report says Request for Proposal stage sees repeated delays

- Centre follows nine stages before a major defence deal is signed

Did our AI summary help?

Let us know.

New Delhi:

Confronted by a system of arms procurement that lies in tatters, Dr Subhash Bhambre, the Minister of State for Defence, has recommended a series of reforms at each of the nine stages prior to a defence deal being announced. He suggests a change in attitude from laissez-faire to being time-conscious and says "due diligence" cannot be an excuse for mammoth delays.

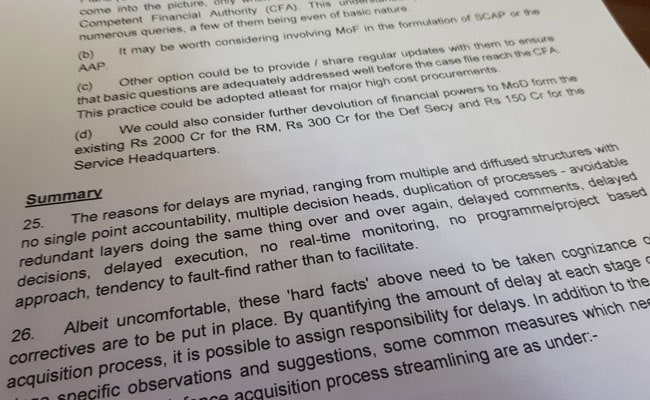

Yesterday, NDTV broke details of why Dr Bhamre felt his ministry was replete with "multiple and diffused structures with no single-point accountability, multiple decision heads, duplication of processes - avoidable redundant layers doing the same thing over and over again, delayed comments, delayed decisions, delayed execution, no real-time monitoring, no programme/project based approach [and a] tendency to fault-find rather than to facilitate." As a result of this mess, of the 144 schemes contracted during the last three financial years, "only 8%-10% fructified within the stipulated time period."

There are nine stages that the government follows before a major defence deal is signed, a process that, in the case of a major acquisition, can easily take more than a decade to be cleared. This means India's armed forces are poorly equipped and frequently have to rely on obsolete weapons systems as they prepare to fight modern wars. The best example of this laboriously slow process is the Indian Air Force's demand for 126 modern fighter jets, first raised in 2001. Seventeen years later, all that has been contracted for are 36 French Rafale fighters, not a single one of which has been delivered so far.

In a 27-point internal report in November last, Dr Bhamre has pointed out that the Request for Proposal (RFP) stage in the Defence Ministry sees repeated delays during the early stages of the deal process. "The average time taken by a scheme at this stage is 120 weeks," six times more than the 20 weeks permitted by the Defence Procurement Procedure 2016, the government's manual on how defence acquisitions have to be managed. This is because of "repeated queries, lesser stress on collegiate meetings, delays in submitting comments/observations, delay in vendor assessment [and] duplication of process," it says.

Now, after a file has been cleared by a collegiate within the system, "there should be no follow up of issues of RFP." What's more, the Defence Ministry collegiate should not meet more than twice to vet the process.

There are several problems which have been identified when a weapon system that is being evaluated enters the trial evaluation state. The average time to complete this "is 89 weeks, which is three times more than that authorised." This is often because field formations which conduct trials "are not adequately equipped or conversant with the trial methodology." In simple terms, officers of the Air Force, Army and Navy may not be experienced enough to deal with the complex assessment process through which a weapon system is graded on multiple parameters before being deemed fit or unfit for use by India's armed forces.

There are several problems which have been identified when a weapon system that is being evaluated enters the trial evaluation state. The average time to complete this "is 89 weeks, which is three times more than that authorised." This is often because field formations which conduct trials "are not adequately equipped or conversant with the trial methodology." In simple terms, officers of the Air Force, Army and Navy may not be experienced enough to deal with the complex assessment process through which a weapon system is graded on multiple parameters before being deemed fit or unfit for use by India's armed forces.

Dr Bhamre suggests that a trial overseeing team speed up this process while the Defence Ministry also explores setting up "well equipped laboratories/test facilities with the necessary international accreditations in specific defence related areas/zones."

Cost negotiating, which "forms the backbone of a successful contract" is another area where delays are the norm. "The average time taken was 60 weeks," says Dr Bhamre, "about 10 times more than that allowed." In one case, cost negotiations with a foreign equipment manufacturer was delayed by "a colossal 273 weeks."

To improve the system here means that that the process to benchmark costs vis-a-vis international standards has to be fine-tuned. To do this, officers in the Defence Ministry need to be educated. India, the minister says, needs "a pool of domain experts trained in negotiating skills, as well as contractual experts." In nations such as the United States, Dr Bhamre explains, "the Defence Acquisition University has an entire course dedicated to cost methodology, where they teach over 18 ways of pricing/benchmarking."

If a file on the purchase of a weapons system actually clears all the hurdles in the Defence Ministry, it is still far from seeing the light of day because the Finance Ministry, which is the Chief Financial Authority (CFA), is presently "not aware of the Services Capital Acquisition Plans or the Annual Acquisition Plan being prepared by the Ministry of Defence."

In other words, the Defence Ministry all along seems to be working in isolation towards clearing a deal only to be confronted by bureaucrats in the Finance Ministry, who end up asking numerous questions late in the deal process, "a few of them being even of basic nature." To stop this, Dr Bhamre suggests "we should consider further devolution of financial powers to the Ministry of Defence" so that decisions can be taken within the ministry. At the moment, the defence minister is empowered to clear deals worth Rs 2,000 crore, the defence secretary is authorised to clear Rs 300 crore and the armed forces can clear projects worth Rs 150 crore without the file needing to move to the Finance Ministry.

In other words, the Defence Ministry all along seems to be working in isolation towards clearing a deal only to be confronted by bureaucrats in the Finance Ministry, who end up asking numerous questions late in the deal process, "a few of them being even of basic nature." To stop this, Dr Bhamre suggests "we should consider further devolution of financial powers to the Ministry of Defence" so that decisions can be taken within the ministry. At the moment, the defence minister is empowered to clear deals worth Rs 2,000 crore, the defence secretary is authorised to clear Rs 300 crore and the armed forces can clear projects worth Rs 150 crore without the file needing to move to the Finance Ministry.

India is notorious for having one of the world's most complicated systems to acquire weaponry.

The process begins when the Army, Navy, Air Force or Coast Guard identify their needs. This is followed by a Right for Information (RFI), when the forces can ask defence manufacturers for details of some of their productions. On the basis of what they receive, a service defines its qualitative requirements. This is then forwarded to the Defence Ministry, which either rejects the demand made by the armed forces or issues an Acceptance of Necessity (AON) that kick-starts the formal process of initiating a defence deal.

Based on an initial shortlist made at the AON stage, the Defence Ministry reaches out to arms manufacturers which it asks for a Request for Proposal (RFP), where interested parties formally respond to the Defence Ministry's invitation. Based on the responses, the Defence Ministry, in conjuction with the armed forces, form a Technical Evaluation Committee (TEC) that examines the capabilities and technical features of weapons systems being assessed for potential purchase. Those systems that meet are shortlisted and sent for Field Evaluation Trials (FET) where they are rigorously tested. The government then forms a Cost Negotiating Committee (CNC) that receives financial bids from the competing firms selected and picks the lowest common bidder.

The lowest common bidder has technically "won" the competition though in the case of India, there is absolutely no guarantee of that translating into a contract unless there is a final go ahead by the Chief Financial Authority (CFA).

In December, NDTV emailed a set of questions on the report on Defence Procurement to the Defence Ministry's spokesperson, who acknowledged them but offered no answers. Separate reminders through phone messages were also acknowledged but, again, no answers were provided.

Yesterday, NDTV broke details of why Dr Bhamre felt his ministry was replete with "multiple and diffused structures with no single-point accountability, multiple decision heads, duplication of processes - avoidable redundant layers doing the same thing over and over again, delayed comments, delayed decisions, delayed execution, no real-time monitoring, no programme/project based approach [and a] tendency to fault-find rather than to facilitate." As a result of this mess, of the 144 schemes contracted during the last three financial years, "only 8%-10% fructified within the stipulated time period."

There are nine stages that the government follows before a major defence deal is signed, a process that, in the case of a major acquisition, can easily take more than a decade to be cleared. This means India's armed forces are poorly equipped and frequently have to rely on obsolete weapons systems as they prepare to fight modern wars. The best example of this laboriously slow process is the Indian Air Force's demand for 126 modern fighter jets, first raised in 2001. Seventeen years later, all that has been contracted for are 36 French Rafale fighters, not a single one of which has been delivered so far.

In a 27-point internal report in November last, Dr Bhamre has pointed out that the Request for Proposal (RFP) stage in the Defence Ministry sees repeated delays during the early stages of the deal process. "The average time taken by a scheme at this stage is 120 weeks," six times more than the 20 weeks permitted by the Defence Procurement Procedure 2016, the government's manual on how defence acquisitions have to be managed. This is because of "repeated queries, lesser stress on collegiate meetings, delays in submitting comments/observations, delay in vendor assessment [and] duplication of process," it says.

Now, after a file has been cleared by a collegiate within the system, "there should be no follow up of issues of RFP." What's more, the Defence Ministry collegiate should not meet more than twice to vet the process.

India is notorious for having one of the world's most complicated systems to acquire weaponry.

Dr Bhamre suggests that a trial overseeing team speed up this process while the Defence Ministry also explores setting up "well equipped laboratories/test facilities with the necessary international accreditations in specific defence related areas/zones."

Cost negotiating, which "forms the backbone of a successful contract" is another area where delays are the norm. "The average time taken was 60 weeks," says Dr Bhamre, "about 10 times more than that allowed." In one case, cost negotiations with a foreign equipment manufacturer was delayed by "a colossal 273 weeks."

To improve the system here means that that the process to benchmark costs vis-a-vis international standards has to be fine-tuned. To do this, officers in the Defence Ministry need to be educated. India, the minister says, needs "a pool of domain experts trained in negotiating skills, as well as contractual experts." In nations such as the United States, Dr Bhamre explains, "the Defence Acquisition University has an entire course dedicated to cost methodology, where they teach over 18 ways of pricing/benchmarking."

If a file on the purchase of a weapons system actually clears all the hurdles in the Defence Ministry, it is still far from seeing the light of day because the Finance Ministry, which is the Chief Financial Authority (CFA), is presently "not aware of the Services Capital Acquisition Plans or the Annual Acquisition Plan being prepared by the Ministry of Defence."

India has revived the deal to buy Spike anti-tank missiles from Israel just weeks after New Delhi had exited the $500 million deal.

India is notorious for having one of the world's most complicated systems to acquire weaponry.

The process begins when the Army, Navy, Air Force or Coast Guard identify their needs. This is followed by a Right for Information (RFI), when the forces can ask defence manufacturers for details of some of their productions. On the basis of what they receive, a service defines its qualitative requirements. This is then forwarded to the Defence Ministry, which either rejects the demand made by the armed forces or issues an Acceptance of Necessity (AON) that kick-starts the formal process of initiating a defence deal.

Based on an initial shortlist made at the AON stage, the Defence Ministry reaches out to arms manufacturers which it asks for a Request for Proposal (RFP), where interested parties formally respond to the Defence Ministry's invitation. Based on the responses, the Defence Ministry, in conjuction with the armed forces, form a Technical Evaluation Committee (TEC) that examines the capabilities and technical features of weapons systems being assessed for potential purchase. Those systems that meet are shortlisted and sent for Field Evaluation Trials (FET) where they are rigorously tested. The government then forms a Cost Negotiating Committee (CNC) that receives financial bids from the competing firms selected and picks the lowest common bidder.

The lowest common bidder has technically "won" the competition though in the case of India, there is absolutely no guarantee of that translating into a contract unless there is a final go ahead by the Chief Financial Authority (CFA).

In December, NDTV emailed a set of questions on the report on Defence Procurement to the Defence Ministry's spokesperson, who acknowledged them but offered no answers. Separate reminders through phone messages were also acknowledged but, again, no answers were provided.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world