In India's season of unrest, the national media has been faulted not entirely without reason, for ignoring this one - 5 months of intermittent strikes at the Maruti Suzuki plant in Manesar. Those strikes maybe over but it is worth exploring the anatomy of the troubles at Maruti - where every claim is fiercely contested: Is India's largest carmaker riding its workers too hard on the road to high profits, and is being vindictive with those who object? Or are a small band of troublemakers, holding to ransom one of India's most reputed companies? Is this a localised bushfire, specific to one company and one location - or a wildfire that acts an early warning of coming wars between labor and capital?

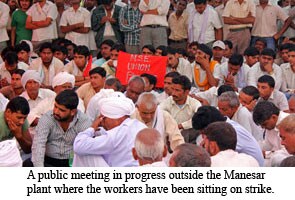

Manesar, Haryana: On the ground, at Manesar hundreds of workers sitting on strike, has been the reality of the past 5 months. These are workers from Maruti's car making plant.

Just around the corner is another set - the latest joinees to the strike - workers from Maruti Powertrain, the company that makes the engines for its cars.

Unrest, falling production and falling stocks that 6 months ago would have been unthinkable for Maruti.

The question of what triggered the unrest is the most contested but almost everyone agrees that a key trigger was when Maruti, under pressure to stay on top in India's hyper competitive car market, stepped on the gas in its two plants - Gurgaon and Manesar.

The car production jumped from 7 lakh cars in 2008-09 to about 10 lakh cars in 2009-10. Maruti accounts for about 50% of car sales in the country.

Maruti's sales soared by almost 50%, from 28,000 crore Rs in 2009 to 36,000 crore Rs in 2010.

Did that pressure begin to tell on the factory floor, raising questions over longstanding work practices at Maruti?

The workers told us:

"The work culture is flawed and there are many restrictions here."

"When I joined in 2006 we used to manufacture 160 cars in a shift. Today we manufacture 430 cars."

"The work load is so much that there is no time to even drink water."

"Even the time for using the bathroom is fixed. We have 2 to 5 minutes to go to the bathroom and can only go once a day."

"Even if there is an emergency at home, we can't get a day off. Even for our own wedding, which happens once in your life, we can't get leave."

"They only have one theory, use and throw. Make them work and then chase them away."

"How can we work in these conditions?"

When he first heard these complaints, MM Singh, Managing Executive Officer of Production at Maruti says he was stunned.

Singh made the changes to Maruti's assembly lines to ramp up output but not at the cost of his workers as he clarified.

Singh says, "It is not true. There is no increase in the load. Workers have got fixed jobs. It is a defined job, within so much time you have to do this much. Nothing more than that."

He admits that the line is tough but that is the nature of factory work.

Walking us through the plant, Singh says, "If you look at the boys, are the really looking very tired? You can look at the faces and understand better. Are they really firefighting anywhere? First mentally they have to be ready, yes I am going to stand for 4 hours, except for the breaks. Otherwise you have to be on the line. You cannot say I'll go away because I am tired. That is not possible. Then it won't be as Assembly Line."

He contests claims they didn't have time to even sip water.

The siren goes off and it is time for a tea and snack break - another bone of contention.

In a high pressure 8 hour shift there are two such 7/12 minute breaks which the striking workers say is hardly enough.

The striking workers said, "During the tea break we have to eat our snacks and use the bathroom within 7 minutes and then reach the station a minute early. For a long time we have been saying that this is wrong. They said that whoever wants to work can work and others can leave and that the system would not change."

In a guided tour of a factory operating at half steam, it is hard for us to judge whether 7 minutes is indeed a sufficient break.

It seems to be in keeping with the rhythms of factory life, a quick and joyless affair before getting back to the line.

We meet Singh at the Gurgaon factory as the Manesar operations are currently not ideal for filming work floor practices at Maruti.

It doesn't matter he says because both follow the same practices.

That is a logic we will hear again and again from Marutis management - if workers in Gurgaon are content, why are there problems in Manesar? Here's one big difference: when Maruti boosted its production the biggest jump was at Manesar, where assembly lines designed for about 600 cars a day cranked out a 1000. The jump in Gurgaon was more gradual.

MANESAR - FROM 630 CARS/DAY TO 1000 CARS/DAY

GURGAON - FROM 1500 CARS/DAY 10 1800 CARS/DAY

(Period: 2008-2010)

So could it be that the pace at the Gurgaon assembly line may not be comparable to what workers at Manesar experienced during the months of peak production?

Maruti Suzuki Chairman, RC Bhargava says, "Not at all. Whatever you can produce in your working shift, you're supposed to produce. It is not the old system which we used to have once upon a time where people negotiated that I will produce only 30 products and if 30 are produced in 5 hours, they took the rest of the 3 hours off.

Another significant reason is that the Manesar workers like the Manesar plant are younger. The plant is only 4 years old which is about the same duration most of these men, some of them almost boys, have worked for Maruti.

SY Siddiqui, Managing Executive Officer, HR at Maruti says, "I think the basic problem that we analyzed is mostly coming from youngsters not able to adapt to the industrial work culture."

Industrial culture or more specifically - Japanese work culture.

Singh shows us a signboard with Japanese work concepts like Seiso for cleaning and Seiton for arrangement, are occasional reminders that even if is operating in the Haryana heartland it has been since 2003, a Japanese company.

The Japanese have brought in efficiency and world class technology, the culture of a flat organization where workers and management eat together.

But most important to them, of all the concepts on the wall is Shitsuke or discipline.

Singh explains, "The most critical at the base we say is the Shitsuke. Discipline in every aspect, shop floor discipline is must. If you're encouraging indiscipline in the shop floor, you'll be nowhere."

Where does the line get drawn between discipline and unfair practice?

For example - a worker who is late even by a second, loses half a day's wages.

One of the workers says, "Even if we are late by a minute we are marked absent."

Singh says, "With folded hands I tell my people to not be late. You are going to make a problem for everybody"

Yes punctuality on the line is important. But is Maruti harsher than others?

We just checked to see how it works in the industry and asked Hyundai about the punishment for the same delay. For being late upto 30 minutes they only subtract one hour of the worker's wage, which seems less harsh.

Siddiqui says, "Typically each company, each corporate will see it in their own perspective, how they would like to define it."

Maruti's Standing Orders for its Manesar plant, the rulebook for its workers lists a staggering 111 acts of misconduct. These include like gossiping or singing songs or remaining in the toilet for too long.

Siddiqui says, "No no I don't think so it's excessive. It's a very normal template which you pick up from 100 companies. You will find very common stuff coming in out there which they just copy paste and put it for certification."

Standard practices in ordinary times perhaps but these have not been ordinary times for Maruti. Throw in to the mix a speeded up production, a young workforce, a new plant, and a strict - too strict rule book, and you may have the recipe for months of labour unrest.

When Maruti's workers first went on strike on June 4th none of this was anticipated.

The workers at that time had claimed they didn't have a platform to raise these grievances. The existing Maruti union MUKU is alleged to be controlled by the management and hasn't held proper elections in 11 years.

Workers said, "It is a pocket union which belongs to the management. They do exactly what the management tells them to do. We want to create a separate union for ourselves."

Maruti brushed this aside by sacking 11 workers and holding elections to its union that same month, calling it a coincidence.

Siddiqui says, "Typically there was also a process simultaneously going on as a coincidence, since June 2011 for the current union of Gurgaon to go through a secret ballot election and when this happened on 16th July and an entirely new set of people came in that have never been in the union earlier so there is no question of this being a management union or whatever"

That first strike lasted only about a week and ended with a settlement in which the workers were taken back affirming the management's view that it was just a flash in the pan but instead, within days both sides accused each other of breaching the peace.

The workers showed samples, an image and a cellphone video of a worker being beaten by a supervisor of the as an example of the abuse - and victimization.

The management reacted by releasing a catalogue of mostly minor and a few major damage to equipment in the Manesar plant as proof of sabotage by troublemakers that were behind the initial protests.

The striking workers said there was no sabotage and that their members were forced into making errors by suddenly being assigned to different roles.

One such worker Dev Pal speaking to us says, "I worked in the workshop for 4 years. Then they sent me to the assembly. I don't know how to do anything there. The supervisors abuse us there."

Arun Kumar, another young worker says, "They shifted me from one shop assembly to another in the weld shop. I don't know how to do any of the work there."

As the unrest continued, another contentious labor practice came to the fore represented by men like Rakesh Kumar, a labour contractor.

Rakesh tells us," We have placed around 500-600 contract workers in Manesar and 200 people in Suzuki Motorcycles."

Rakesh runs Tirupati Associates, from his office, just across the road from Gurgaon plant which supplies contract labor to Maruti for the past 15 years.

Contract workers are paid roughly Rs. 8000, about half of what permanent employees earn, and without any of the protection.

This time matters went out of hand when Rakesh's brother Satish was beaten up because he went with a group of contractors to 'rescue' contract workers from the plant of Suzuki Motorcyles, one of the Maruti companies that had joined the strike.

Workers say Satish had fired a gun in the air and so they had to retaliate. Avinesh Kumar, one of the Suzuki bike plant workers tells us, "Our boys got involved when the gun went off. We went and snatched their revolver. Things happen in such situations."

But Rakesh says his brother was attacked without provocation and his car, a Toyota Corolla smashed.

Rakesh says, "He was surrounded and attacked as soon as he reached there. They broke the windows of my car. It is still lying at the police station."

Regardless of the veracity of these claims, this episode highlighted an unusual alliance between two traditional rivals - permanent and contract workers. The current protest is permanent workers of Maruti striking to get the management to take back 1200 contract workers who joined them.

The management reacted by giving us a video which they claim exposes this solidarity. It is shot by one of their guards in October, when the workers had staged a sit in inside the plant taking partial control over it.

They say the video shows how contract workers were coerced into taking part in the strike and were beaten when they tried to escape.

In the video clips contract workers accuse permanent workers, saying:

"They forced us off the line and then took our gate passes as well."

"They dragged us off the line and then even slapped us."

"They threatened us saying when we came out they would beat us."

Even if that solidarity can be questioned what about another one which we witnessed in Kamala Nehru Park in Gurgaon, at a rally in support of the Maruti workers?

Unions from the auto belt were heavily represented, from component maker FCC Rico to Satyam Auto to Hero Motorcycles.

Taking turns on stage is the full public display of the traditional trade unions - CITU, AITUC, BMS that have been a behind the scenes guide to the Maruti workers through these months.

To the management these are the outside forces that have led their boys astray.

Bhargava says, "Basically, people from outside, I do not know if they are politically affiliated...Unions, ex-employees of Maruti, outsiders of any kind who have some grudge."

To the older unions this is a sign of Maruti workers entering their fold.

But others say that while the established unions did provide advice, the Maruti workers have kept their independence.

Rakhi Sehgal from New Trade Union Initiative (NTUI) says, "They have been talking to everybody. They have also been talking to us. Using us as a sounding board as they try and figure out what strategy they want to follow."

But while the strike may have been a demonstration of a nascent labour movement in Maruti, and indeed in the Gurgaon-Manesar carmaking belt, it also showed signs of managements of this belt, are weighing their options - among which is whether benefits of doing business in this belt are outweighing risks.

A day after the strike ends we come across a gridlock outside the Maruti plant gates in Gurgaon. These are longtime Maruti workers, driving up in their Maruti cars - which bolster the management's claims that they have shared the benefits of India's car boom with the Haryana hinterland.

But this is not a politically passive hinterland. During the days of protests, sarpanches of the villages from Manesar had come to speak in support of their boys.

So is Maruti looking outside of Haryana - to less restive states like Gujarat ? They say they always were but they will never leave Haryana.

Bhargava says, "There is an industry friendly climate that exists in Gujarat and the ease of getting decisions done and the speed with which decisions are made in Gujarat is another positive factor."

Instead it is the changes at home to prepare for fresh unrest that maybe worth noting. Maruti's contractors spell out what the management cannot.

Ajay Kumar Dangi, Contractor, Dangi Enterprises says, "Seeing today's climate, we are beginning to avoid workers from Haryana as there is too much involvement of local politics."

We saw that change inside the Manesar plant during the days of the strike. Maruti ran scaled down operations with hundreds of contract workers, mostly from outside Haryana.

And by converting its unused factory floors into makeshift hostels for Haryana police.

At the Manesar plant, P.C. Roy of Maruti says, "It is fully automated. No spot welding is done manually here. We have about 250 odd robots."

And at the end of our tour of the Manesar plant we are shown its robotic assembly and welding line - the game changer that can lead to better efficiency. And of course it comes protest-free.

And so is this a lesson from Maruti? - if the protests are as much a successful show of test of strength of a new generation of union leaders, it was as much a dress rehearsal for Maruti management and for factory owners everywhere of new generation methods of tackling labor unrest.

(Inputs and photos - Niha Masih)

Manesar, Haryana: On the ground, at Manesar hundreds of workers sitting on strike, has been the reality of the past 5 months. These are workers from Maruti's car making plant.

Just around the corner is another set - the latest joinees to the strike - workers from Maruti Powertrain, the company that makes the engines for its cars.

Unrest, falling production and falling stocks that 6 months ago would have been unthinkable for Maruti.

The question of what triggered the unrest is the most contested but almost everyone agrees that a key trigger was when Maruti, under pressure to stay on top in India's hyper competitive car market, stepped on the gas in its two plants - Gurgaon and Manesar.

The car production jumped from 7 lakh cars in 2008-09 to about 10 lakh cars in 2009-10. Maruti accounts for about 50% of car sales in the country.

Maruti's sales soared by almost 50%, from 28,000 crore Rs in 2009 to 36,000 crore Rs in 2010.

Did that pressure begin to tell on the factory floor, raising questions over longstanding work practices at Maruti?

The workers told us:

"The work culture is flawed and there are many restrictions here."

"When I joined in 2006 we used to manufacture 160 cars in a shift. Today we manufacture 430 cars."

"The work load is so much that there is no time to even drink water."

"Even the time for using the bathroom is fixed. We have 2 to 5 minutes to go to the bathroom and can only go once a day."

"Even if there is an emergency at home, we can't get a day off. Even for our own wedding, which happens once in your life, we can't get leave."

"They only have one theory, use and throw. Make them work and then chase them away."

"How can we work in these conditions?"

When he first heard these complaints, MM Singh, Managing Executive Officer of Production at Maruti says he was stunned.

Singh made the changes to Maruti's assembly lines to ramp up output but not at the cost of his workers as he clarified.

Singh says, "It is not true. There is no increase in the load. Workers have got fixed jobs. It is a defined job, within so much time you have to do this much. Nothing more than that."

He admits that the line is tough but that is the nature of factory work.

Walking us through the plant, Singh says, "If you look at the boys, are the really looking very tired? You can look at the faces and understand better. Are they really firefighting anywhere? First mentally they have to be ready, yes I am going to stand for 4 hours, except for the breaks. Otherwise you have to be on the line. You cannot say I'll go away because I am tired. That is not possible. Then it won't be as Assembly Line."

He contests claims they didn't have time to even sip water.

The siren goes off and it is time for a tea and snack break - another bone of contention.

In a high pressure 8 hour shift there are two such 7/12 minute breaks which the striking workers say is hardly enough.

The striking workers said, "During the tea break we have to eat our snacks and use the bathroom within 7 minutes and then reach the station a minute early. For a long time we have been saying that this is wrong. They said that whoever wants to work can work and others can leave and that the system would not change."

In a guided tour of a factory operating at half steam, it is hard for us to judge whether 7 minutes is indeed a sufficient break.

It seems to be in keeping with the rhythms of factory life, a quick and joyless affair before getting back to the line.

We meet Singh at the Gurgaon factory as the Manesar operations are currently not ideal for filming work floor practices at Maruti.

It doesn't matter he says because both follow the same practices.

That is a logic we will hear again and again from Marutis management - if workers in Gurgaon are content, why are there problems in Manesar? Here's one big difference: when Maruti boosted its production the biggest jump was at Manesar, where assembly lines designed for about 600 cars a day cranked out a 1000. The jump in Gurgaon was more gradual.

MANESAR - FROM 630 CARS/DAY TO 1000 CARS/DAY

GURGAON - FROM 1500 CARS/DAY 10 1800 CARS/DAY

(Period: 2008-2010)

So could it be that the pace at the Gurgaon assembly line may not be comparable to what workers at Manesar experienced during the months of peak production?

Maruti Suzuki Chairman, RC Bhargava says, "Not at all. Whatever you can produce in your working shift, you're supposed to produce. It is not the old system which we used to have once upon a time where people negotiated that I will produce only 30 products and if 30 are produced in 5 hours, they took the rest of the 3 hours off.

Another significant reason is that the Manesar workers like the Manesar plant are younger. The plant is only 4 years old which is about the same duration most of these men, some of them almost boys, have worked for Maruti.

SY Siddiqui, Managing Executive Officer, HR at Maruti says, "I think the basic problem that we analyzed is mostly coming from youngsters not able to adapt to the industrial work culture."

Industrial culture or more specifically - Japanese work culture.

Singh shows us a signboard with Japanese work concepts like Seiso for cleaning and Seiton for arrangement, are occasional reminders that even if is operating in the Haryana heartland it has been since 2003, a Japanese company.

The Japanese have brought in efficiency and world class technology, the culture of a flat organization where workers and management eat together.

But most important to them, of all the concepts on the wall is Shitsuke or discipline.

Singh explains, "The most critical at the base we say is the Shitsuke. Discipline in every aspect, shop floor discipline is must. If you're encouraging indiscipline in the shop floor, you'll be nowhere."

Where does the line get drawn between discipline and unfair practice?

For example - a worker who is late even by a second, loses half a day's wages.

One of the workers says, "Even if we are late by a minute we are marked absent."

Singh says, "With folded hands I tell my people to not be late. You are going to make a problem for everybody"

Yes punctuality on the line is important. But is Maruti harsher than others?

We just checked to see how it works in the industry and asked Hyundai about the punishment for the same delay. For being late upto 30 minutes they only subtract one hour of the worker's wage, which seems less harsh.

Siddiqui says, "Typically each company, each corporate will see it in their own perspective, how they would like to define it."

Maruti's Standing Orders for its Manesar plant, the rulebook for its workers lists a staggering 111 acts of misconduct. These include like gossiping or singing songs or remaining in the toilet for too long.

Siddiqui says, "No no I don't think so it's excessive. It's a very normal template which you pick up from 100 companies. You will find very common stuff coming in out there which they just copy paste and put it for certification."

Standard practices in ordinary times perhaps but these have not been ordinary times for Maruti. Throw in to the mix a speeded up production, a young workforce, a new plant, and a strict - too strict rule book, and you may have the recipe for months of labour unrest.

When Maruti's workers first went on strike on June 4th none of this was anticipated.

The workers at that time had claimed they didn't have a platform to raise these grievances. The existing Maruti union MUKU is alleged to be controlled by the management and hasn't held proper elections in 11 years.

Workers said, "It is a pocket union which belongs to the management. They do exactly what the management tells them to do. We want to create a separate union for ourselves."

Maruti brushed this aside by sacking 11 workers and holding elections to its union that same month, calling it a coincidence.

Siddiqui says, "Typically there was also a process simultaneously going on as a coincidence, since June 2011 for the current union of Gurgaon to go through a secret ballot election and when this happened on 16th July and an entirely new set of people came in that have never been in the union earlier so there is no question of this being a management union or whatever"

That first strike lasted only about a week and ended with a settlement in which the workers were taken back affirming the management's view that it was just a flash in the pan but instead, within days both sides accused each other of breaching the peace.

The workers showed samples, an image and a cellphone video of a worker being beaten by a supervisor of the as an example of the abuse - and victimization.

The management reacted by releasing a catalogue of mostly minor and a few major damage to equipment in the Manesar plant as proof of sabotage by troublemakers that were behind the initial protests.

The striking workers said there was no sabotage and that their members were forced into making errors by suddenly being assigned to different roles.

One such worker Dev Pal speaking to us says, "I worked in the workshop for 4 years. Then they sent me to the assembly. I don't know how to do anything there. The supervisors abuse us there."

Arun Kumar, another young worker says, "They shifted me from one shop assembly to another in the weld shop. I don't know how to do any of the work there."

As the unrest continued, another contentious labor practice came to the fore represented by men like Rakesh Kumar, a labour contractor.

Rakesh tells us," We have placed around 500-600 contract workers in Manesar and 200 people in Suzuki Motorcycles."

Rakesh runs Tirupati Associates, from his office, just across the road from Gurgaon plant which supplies contract labor to Maruti for the past 15 years.

Contract workers are paid roughly Rs. 8000, about half of what permanent employees earn, and without any of the protection.

This time matters went out of hand when Rakesh's brother Satish was beaten up because he went with a group of contractors to 'rescue' contract workers from the plant of Suzuki Motorcyles, one of the Maruti companies that had joined the strike.

Workers say Satish had fired a gun in the air and so they had to retaliate. Avinesh Kumar, one of the Suzuki bike plant workers tells us, "Our boys got involved when the gun went off. We went and snatched their revolver. Things happen in such situations."

But Rakesh says his brother was attacked without provocation and his car, a Toyota Corolla smashed.

Rakesh says, "He was surrounded and attacked as soon as he reached there. They broke the windows of my car. It is still lying at the police station."

Regardless of the veracity of these claims, this episode highlighted an unusual alliance between two traditional rivals - permanent and contract workers. The current protest is permanent workers of Maruti striking to get the management to take back 1200 contract workers who joined them.

The management reacted by giving us a video which they claim exposes this solidarity. It is shot by one of their guards in October, when the workers had staged a sit in inside the plant taking partial control over it.

They say the video shows how contract workers were coerced into taking part in the strike and were beaten when they tried to escape.

In the video clips contract workers accuse permanent workers, saying:

"They forced us off the line and then took our gate passes as well."

"They dragged us off the line and then even slapped us."

"They threatened us saying when we came out they would beat us."

Even if that solidarity can be questioned what about another one which we witnessed in Kamala Nehru Park in Gurgaon, at a rally in support of the Maruti workers?

Unions from the auto belt were heavily represented, from component maker FCC Rico to Satyam Auto to Hero Motorcycles.

Taking turns on stage is the full public display of the traditional trade unions - CITU, AITUC, BMS that have been a behind the scenes guide to the Maruti workers through these months.

To the management these are the outside forces that have led their boys astray.

Bhargava says, "Basically, people from outside, I do not know if they are politically affiliated...Unions, ex-employees of Maruti, outsiders of any kind who have some grudge."

To the older unions this is a sign of Maruti workers entering their fold.

But others say that while the established unions did provide advice, the Maruti workers have kept their independence.

Rakhi Sehgal from New Trade Union Initiative (NTUI) says, "They have been talking to everybody. They have also been talking to us. Using us as a sounding board as they try and figure out what strategy they want to follow."

But while the strike may have been a demonstration of a nascent labour movement in Maruti, and indeed in the Gurgaon-Manesar carmaking belt, it also showed signs of managements of this belt, are weighing their options - among which is whether benefits of doing business in this belt are outweighing risks.

A day after the strike ends we come across a gridlock outside the Maruti plant gates in Gurgaon. These are longtime Maruti workers, driving up in their Maruti cars - which bolster the management's claims that they have shared the benefits of India's car boom with the Haryana hinterland.

But this is not a politically passive hinterland. During the days of protests, sarpanches of the villages from Manesar had come to speak in support of their boys.

So is Maruti looking outside of Haryana - to less restive states like Gujarat ? They say they always were but they will never leave Haryana.

Bhargava says, "There is an industry friendly climate that exists in Gujarat and the ease of getting decisions done and the speed with which decisions are made in Gujarat is another positive factor."

Instead it is the changes at home to prepare for fresh unrest that maybe worth noting. Maruti's contractors spell out what the management cannot.

Ajay Kumar Dangi, Contractor, Dangi Enterprises says, "Seeing today's climate, we are beginning to avoid workers from Haryana as there is too much involvement of local politics."

We saw that change inside the Manesar plant during the days of the strike. Maruti ran scaled down operations with hundreds of contract workers, mostly from outside Haryana.

And by converting its unused factory floors into makeshift hostels for Haryana police.

At the Manesar plant, P.C. Roy of Maruti says, "It is fully automated. No spot welding is done manually here. We have about 250 odd robots."

And at the end of our tour of the Manesar plant we are shown its robotic assembly and welding line - the game changer that can lead to better efficiency. And of course it comes protest-free.

And so is this a lesson from Maruti? - if the protests are as much a successful show of test of strength of a new generation of union leaders, it was as much a dress rehearsal for Maruti management and for factory owners everywhere of new generation methods of tackling labor unrest.

(Inputs and photos - Niha Masih)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world