Yet, there was also disenchantment and disappointment with the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). Its spokespersons' trademark belligerence, its government's resort to gimmickry (the odd-even scheme that achieved precious little), and the party's and Kejriwal's ambition to foray into national politics and other states, rather than focus on the sobriety of governance, all hurt it. In that sense, two separate anti-incumbencies - at the municipal and state government levels - cancelled each other out.

The BJP responded by changing its candidates and riding on the momentum of its recent victory in Uttar Pradesh - which must have given it a fillip with the Purbaiyya (migrants from eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar) vote in Delhi and generally energized party workers. It subliminally presented this as an election where the voter could repose faith in an all-India pro-Modi move.

That the party organisation is in better shape than in 2015, when the BJP was thrashed in Delhi, also helped. Infighting in the BJP unit has been something of an epidemic for decades now. In previous years, municipal or assembly ticket distribution led to dissent and even violence. This time, close to all candidates from 2012 were changed but the rebellion and the breakaway groups were contained. The authority of the party leadership remained intact. This is a big achievement for Amit Shah who had been nonplussed and exasperated by the notoriously divided Delhi unit in 2015.

Party chief Amit Shah's planning is one of the key reasons for BJP's victory in the MCD elections

In December 2013, AAP made a spectacular debut in Delhi politics, coming a close second in the assembly election. It won angry, emotional votes - in an atmosphere of fatigue with mainstream politics and hostility to Congress governments at the centre and in the capital. The unpopularity of the 10-year Manmohan Singh government damaged the local Sheila Dikshit government as well, in an urbanised state very influenced by national political debates. (Similarly, the popularity of the Modi government has helped the local BJP this time but that's another story.)

The 2013 votes that AAP won were protest votes and votes for an amorphous sense of restlessness. They were not necessarily pro-Kejriwal votes. In February 2015, however, AAP's victory had a positive impulse to it and was a mandate for the leadership of Kejriwal. The party rose with him, and would either rise further or fall with him, with his stature and with his performance. In that reckoning, the 2017 municipal results indicate Delhi voters are sending Kejriwal a tough message.

What next for the Delhi Chief Minister? His national plans have crashed and any hope of AAP putting up a good fight in Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh later this year seem far away. He has to battle to reverse the slide in Delhi. He will face internal challenges and will probably offer to resign, with the prior arrangement that his support staff will acclaim him and urge him not to quit.

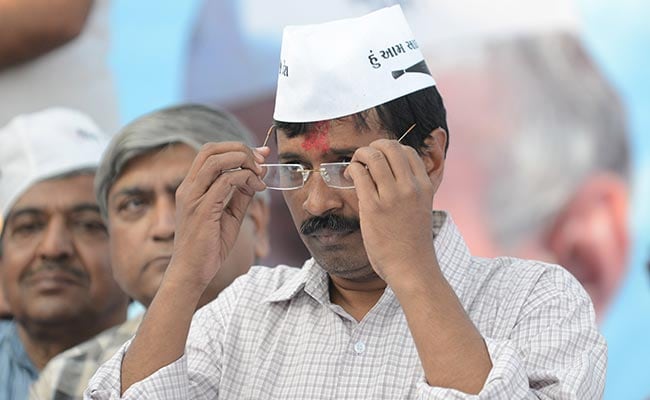

The municipal elections in Delhi are a severe setback for Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal

It is a cliché to suggest that nobody ever retires or is finished in Indian politics. That is true, but sometimes the effective life of a shooting-star politician can be very short. The political fixture may survive, but not the political phenomenon. In November 1989, VP Singh, the anti-corruption crusader of his time and as much a gimmick maestro as Kejriwal - he too campaigned against electronic voting machines - spearheaded an opposition effort to defeat the Congress. A popular figure of the moment, signifying hope, he became Prime Minister amid widespread goodwill.

Two years later, by the winter of 1991, the Congress was ensconced in power once again, India was discussing liberalisation, the BJP was the rising force - and VP Singh was irrelevant in national politics. His effective career was over. He remained important only for old loyalists and friendly journalists turning to him for a quote, a maudlin sentiment or a conspiracy theory.

In 2015, as an anti-corruption figure and a giant killer, VP Singh may have been a model for Arvind Kejriwal. In 2017, he is a warning.

(The author is distinguished fellow, Observer Research Foundation. He can be reached at malikashok@gmail.com)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.