The flutter was essentially on the social media. Expert opinion was less panicked. At the saffron-tinged Vivekananda Foundation, its director, Gen. N.C. Vij, former chief of army staff, described Khan's statement as "immature and outlandish". Another defence expert, Rameshwar Rai, rubbished it as "irresponsible and inconsequential". At the Centre for Air Warfare, Air Vice Marshall Manmohan Bahadur dismissed Khan's remarks as "a mere publicity stunt". At the Society for Policy Studies, Commodore C. Uday Bhaskar (retd) called the publicity stunt "old hat" while retired Brigadier Gurmeet Kanwal at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses stressed that Khan is notorious for his "exaggerated claims". Official India decided - wisely - to let the remark go. The episode has, in effect, been canned.

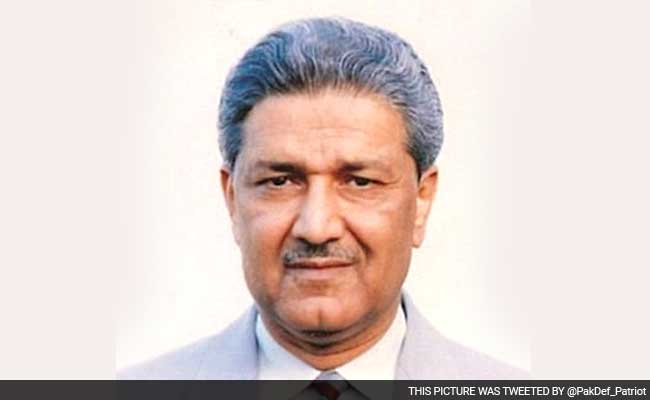

Pakistan has the ability to "target" Delhi in five minutes, the father of Pakistan's nuclear programme Dr Abdul Qadeer Khan said at an event marking 18 years since Pak's first nuclear tests

A major reason why the Cold War did not escalate into a hot nuclear exchange was widespread public knowledge about the catastrophe that would follow any use of nuclear weapons. Apart from scientific and scholarly studies, novels like Neville Shute's On The Beach mobilized public information and concern. In contrast, 18 years after India and Pakistan went overtly nuclear, only one study, by M.V. Ramana, then of MIT and now of Princeton, appears to have tried to hypothesize on the subject, the title of Ramana's 1999 paper being "Bombing Bombay?: Effects of Nuclear Weapons and a Case Study of a Hypothetical Explosion."

The "hypothetical explosion" was assumed to be in the range of 15,000 to 1,50,000 tonnes (that is, 15-150 kilotons, as contrasted to the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki which were in the 10-20 kiloton range). Raman calculated that "for a 15 kiloton explosion, the number of deaths would range between 1,60,000 and 8,66,000. A 150 kiloton weapon would cause somewhere between 7,36,000 and 8.6 million deaths," cautioning that "these estimates are conservative and there are a number of reasons to expect that the actual numbers would be much higher." He added that "several hundreds of thousands of people would suffer from injuries or burns" and that "many of them would die without prompt medical aid". Also that cancers and genetic mutations would affect future generations. The ghastly environmental consequences, including possible "nuclear winter", were also not taken into account. All these add up.

Shaheen III surface-to-surface ballistic missile launching from an undisclosed location in Pakistan, in Dec 2015. It can carry nuclear warheads up to 2,750 kms bringing many Indian cities within its range.

Although such hypotheses might be categorized as "guesswork", the fact is that successive governments since we went nuclear in 1998 have either not attempted to scientifically gauge the consequences of a nuclear attack or have deliberately refrained from taking the public into confidence. This makes most Indians thoroughly gung-ho about our nuclear arsenal. It has also left almost all Indians neither remembering nor wanting to remember Mahatma Gandhi's prescient warning that "the atomic bomb has deadened the finest feeling that has sustained mankind for ages" and Nehru's more practical point that "these weapons, and the magnitude in which they will be employed, have erased the differences between the capacity to inflict punishment and of receiving the same". And, as Rajiv Gandhi said when in 1988 he presented to the United Nations his Action Plan for a Nuclear Weapons-Free and Non-Violent World Order: "There is nothing more dangerous than the illusion of limited nuclear war. It desensitizes inhibitions about the use of nuclear weapons that could lead, in next to no time, to the outbreak of full-fledged nuclear war." The remark was addressed then to the US and the USSR, but applies equally now to nuclear-armed India and Pakistan.

MIT assistant professor of political science and member of their security studies programme, Vipin Narang, has distinguished Pakistan's nuclear doctrine as "asymmetrical escalation" from India's doctrine that he describes as "assured retaliation". He explains in his Nuclear Strategy in The Modern Era: Regional Powers and International Conflict, which has received recognition as the best work on the subject in 2015, that while Pakistan retains the right of "first use" of nuclear weapons in the event of Indian conventional forces substantially intruding into Pakistani territory, India has abjured "first use" because it perceives no conventional threat that it cannot deal with without resorting to the threat or use of nuclear weapons, but has reserved its right to retaliate with nuclear weapons in the event of a nuclear attack. The problem is, as the head of DRDO told India Today, 3 July 2013, that "we are making much more agile, fast-reacting, stable missiles so response can be within minutes". Thus, any "five-minute" nuclear attack by Pakistan will receive an Indian nuclear response "within minutes", bringing on to the heads of both countries an unmitigated nuclear disaster. To quote again from Rajiv Gandhi's 1988 speech at the UN: "the insane logic of mutually assured destruction will ensure that nothing survives, that no one lives to tell the tale, that there is no one left to understand what went wrong and why".

Two imperatives follow.

One, that we ensure through continual dialogue with Pakistan that nothing happens on our part to trigger "asymmetric escalation" on their part, leading, of course, to their "assured destruction" but not before they have rained nuclear havoc on us.

Two, that we revive and canvass an updated version of the Action Plan. Two very recent developments off the "breaking news" radar give cause for a glimmer of hope. The first is that the Modi government has invoked the Rajiv Action Plan in the defence they have presented to the International Court of Justice in The Hague in the case brought by the Marshall Islands (victim of US nuclear testing) against all states that have demonstrated nuclear weapons capability. Second, that the UN-sponsored Open Ended Working Group on nuclear disarmament, an unique forum that brings together on the same platform representatives of governments and civil society activists, has but a few weeks ago taken cognizance of the 1988 Rajiv Gandhi Action Plan as the only roadmap to disarmament ever presented to the international community by a head of government. Are we going to press on with that initiative or complacently give ourselves over to visions of "wiping Pakistan off the map"?

(Mani Shankar Aiyar is former Congress MP, Rajya Sabha.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.