Let's be clear about one thing: the driving force behind the rejection of NSG membership for India was China. The People's Republic has sought to hide behind procedure, claiming that exceptions to outdated non-proliferation rules cannot be made for India. This is obviously hypocritical; China expects, for example, that any number of other international rules need to be bent to serve its own rise. Just look at its behaviour in the South China Sea, where it seems to expect that the law of the sea should not apply to its actions.

China's assertion on procedure amounts to an insistence that Pakistan should be considered for NSG membership at the same time as India. This is, for obvious reasons, farcical; no any objective consideration of the two countries' records on nuclear proliferation suggests they're comparable. Pakistan has been continually and consistently unreliable on it; India, whatever its past behaviour, has since the late 1990s tests, lived up to international non-proliferation commitments - even though it has signed no treaty compelling it to do so.

The takeaways from this NSG fiasco are two-fold.

The first is that China has now shown us its hand. More explicitly than ever before, it has told the world this: that it does not - and will not for the foreseeable future - allow India its natural space in the world. The leaders of the People's Republic do not intend to enable India's rise the way they expect and demand the rest of the globe support China's own rise.

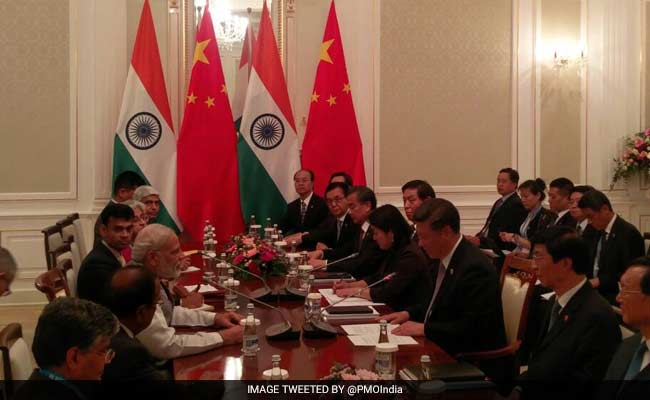

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a meeting in Tashkent on Thursday on the sidelines of SCO Summit

Naturally, this is not an argument for not deepening and strengthening our ties with China. Creating a closer relationship with China is a necessary part of any effort to change minds in Beijing about how they should deal with India. (The same basic logic applies, of course, to our efforts to deepen and strengthen ties with Pakistan.)

But that does not mean that we can deny reality. And the reality is this: of the US and China, only one has committed to viewing India as a great world power, to detaching its association with Pakistan with its connection to India, and to giving India the place it deserves in global institutions. Indian foreign policy must reflect this difference, regardless of what Delhi's congenitally anti-American elites believe. In such a choice, where no balance is offered, no balance can be achieved. Let all talk of 21st-century non-alignment now end.

The second lesson is that India must make its vision of its own future clear. It needs to make explicitly what it expects and deserves: a global order that unequivocally recognises India's position as the world's fastest-growing large economy, the world's largest democracy - and soon its largest country, bar none.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Chinese President Xi Jinping arriving for a group photo ahead of the SCO summit in Tashkent (PTI photo)

This might indeed require exceptions to long-standing rules or norms. It could indeed need global agreements to have conscious India exceptions. There is nothing to be ashamed of in this; it is merely realistic. This country is too large, and is changing too quickly, for things to be otherwise. And it is too large and too important for the worlds' future for denying exceptions to be morally defensible.

India's diplomacy needs to make this vision of our future as explicit as possible, given that it is both morally justified and necessary.

Yes, foreign policy under Narendra Modi has focused on raising India's profile. Foreign Secretary S Jaishankar has at various points laid out the argument that India must transition from being a "balancing" to being a "leading" power.

But there needs to be more coherent messaging. The NSG fiasco, which sets back this country's necessary campaign for a more just global order, certainly reveals that much. If it was unlikely that China would change its mind, then it is unclear why we pushed.

In 2008, when India was given access to certain NSG privileges, a big reason was because the American president could ask a favour of China's paramount leader. Perhaps President Obama did not want to ask with enough passion; perhaps he could not, given his lame-duck status; perhaps this paramount leader is less well disposed to his neighbours than 2008's. All of these should have been taken into consideration; were they? If so, what thinking underlay the decision to push through anyway? We deserve an answer. The government's desire for quick, positive headlines at home must not be allowed to obscure our larger aims.

And even after the decision to push at the NSG was taken, is this really the best outcome? To have states like Brazil and South Africa, nominally our partners in BRICS, nevertheless contribute to procedural objections to a discussion of the Indian exception? What should have been China vs the world turned into something far messier. That is a serious setback, and one that should not be minimised.

India's membership of the NSG on its own terms is not about the arcana of international law. It is not even about the nuclear trade. It is about creating, as smoothly as possible, a global order that recognises the place in the world that India will inevitably occupy. Our government's job is to guide the world to the recognition of this inevitability.

(Mihir Swarup Sharma is a fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.