It has been a tumultuous 25 years, with many ups and downs, many unexpected twists and turns, many gifts of destiny and some cruel blows of fate. I have, in effect, been a leaf in the wind: when the wind has blown in the right direction, I have been lifted up towards the sky; when the wind has fallen, I have sunk low towards the ground.

My acquaintance with parliament is, however, more than half a century long. I first went there as an 18-year old college student; then as Private Secretary to a minister, Dinesh Singh; then fairly frequently as a Joint Secretary in the Ministry of External Affairs; and then pretty regularly as Joint Secretary to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. This moment of parting is, therefore, perhaps a fitting opportunity to share some moments from the past.

Senior Congress Party leader Mani Shankar Aiyar is seen at the joint India-Pakistan border crossing of Wagah, near Amritsar. (AP Photo)

The House heard him out in total, if stunned, silence. There was none of the barracking and noisy interruptions that have now come to characterize our proceedings. Panditji rose to his feet and, with great dignity, began his reply. It was then and there that I decided I must make it one day to the floor of the House. But there was nothing I did, or could do, to bring that about. It happened entirely because of the benign benediction of Rajiv Gandhi.

Senior Congress Party leader Mani Shankar Aiyar speaks to the media. (AP Photo)

That is where Destiny took matters in hand. The relatively young Congress MP for Mayiladuturai in Tamil Nadu, Pakeer Mohammed, suddenly died in a diabetic coma. I sought a ticket to replace him. Rajiv was astonished as he thought I was angling for a Rajya Sabha seat. He was right in assuming there would be tremendous objection from the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee to my being helicoptered into their territory. The immensely powerful GK Moopanar made the argument that I could not possibly win. I am told that in the Parliamentary Board it was PV Narasimha Rao who came to my rescue saying, "Then, let him lose. In politics, you have to learn both to win and lose. Let him begin by learning to lose."

Thus, on the assurance that I would lose, I was given the Congress ticket. In the event, I won by over 1.5 lakh votes. But that too had nothing to do with me. I won because I suffered the worst loss of my political life: Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated on his way to my constituency. I was carried to victory on the sympathy wave that swept the state - but was then left on uncharted seas to make my way without the oar on which I had depended to keep me afloat.

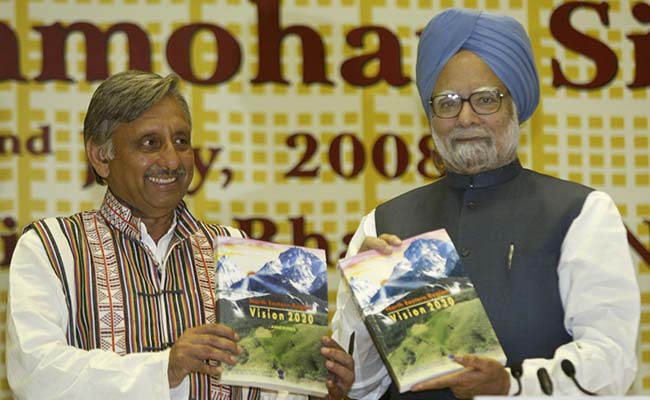

Then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh (right) with senior Congress party leader Mani Shankar Aiyar releasing 'Vision Document 2020 for the North-Eastern Region' in New Delhi in 2008. (AP photo)

It was during that time - 1999 - that the Kargil war broke out. Researching for a column, I came across a fascinating little tit-bit in a dog-eared copy of The Hindustan Times datelined 26 October 1962, bang in the middle of the India-China war. The tiny news item said the leader of a small opposition party, the 36-year old Atal Behari Vajpayee, had called on Prime Minister Nehru to demand that the Rajya Sabha be summoned to discuss the course of the war. Nehru immediately agreed. Within a fortnight, on 8 November 1962, with war clouds hanging in the air, the Rajya Sabha met - and Vajpayee lashed out at the Prime Minister of the day. That was parliamentary democracy at its best.

Reminding Vajpayee of this, I sought through my fortnightly column in The Indian Express to reinforce the Congress demand that the Rajya Sabha be convened to discuss the Kargil war. Prime Minister Vajpayee declined. That was how far standards had fallen between Nehru circa 1962 and Vajpayee circa 1999.

Mr Aiyar protesting with other lawmakers in August, 2015 after the Lok Sabha Speaker suspended 25 members of the Congress for five days for causing "grave disorder" in Parliament. (AP photo)

Compared to the first parliament I had served in, the Tenth, by the time I returned to the House in 1999 for the Thirteenth Lok Sabha, pandemonium was beginning to dominate the proceedings. It only grew worse as the years rolled by and reached their nadir when the BJP found themselves defeated twice in a row, in 2004 and again in 2009. Where, in 2000, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of our Constitution, I had heard Vajpayee repenting that in his day, Opposition MPs would walk out to express their disapproval, they were now beginning to walk in - to the Well of the House - to protest. By 2009, he was too ill to guide the BJP any further, and so the BJP began the dreadful practice of disrupting the House day after day, session after session. Other parties were quick to follow suit. It was at that juncture that, in 2010, I re-entered Parliament in the Rajya Sabha. Entire sessions were abandoned. Legislation, if passed, was often passed without due consideration. Decorum was thrown to the winds. The Chair was mocked and disregarded. Demonstration took precedence over debate. We have now reached the stage where the foundations of the very temple of democracy are being undermined.

There is no point in apportioning the blame - kyonki hamam mein sab nange hain. Something has to be done to restore parliament to its primacy in the consideration of national affairs. The rules have to be re-written to take account the changing social composition of parliament and the fractured nature of our polity, recognizing the harm we do ourselves by prioritizing slogan-shouting on transient issues over sustained debate on matters of enduring national importance.

I leave parliament with a disquieting sense of despair. When the House is in session, the quality of debate is often as good as the best in the world. Can we sustain those standards? I doubt it - but hope and pray we will.

(Mani Shankar Aiyar is former Congress MP, Rajya Sabha.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.