Mr Gandhi was asked the following question: "Why is it that during the years that your family ruled India, India's per capita income was growing less than the world average? And yet, in the years since your family relinquished the prime ministership of India, India's per capita income has grown substantially faster than the world average?"

Mr Gandhi's answer was characteristically indirect, consisting of a general comment about the polarisation in our public discourse with some blaming the Congress for all of India's ills and others praising it for all its strengths; he concluded by attributing India's success largely to its people. Anyone watching it and not familiar with the facts might think that he was stumped. However, even in the era of reality television and talk shows where drama is king, assertiveness equals authority, and opinions are like smartphones as everyone's got one, facts have an annoying habit of interfering with rhetoric.

Irrespective of one's view of the Gandhi-Nehru family and its role in India's economic and political history, the premise of the question happens to be factually wrong. India's growth rate of per capita income broke out of the sluggish levels of the mid-60s to the late-70s in the 1980s, decisively outstripping that of the world and of comparable developing countries at least a decade before the reforms of the early 90s. This has been pointed out by several economists, including by the Chief Economic Advisor of the Modi government, Dr Arvind Subramanian, in a well-known paper. And this was a decade when Indira Gandhi was Prime Minister from 1980-84 and was succeeded by Rajiv Gandhi till 1989.

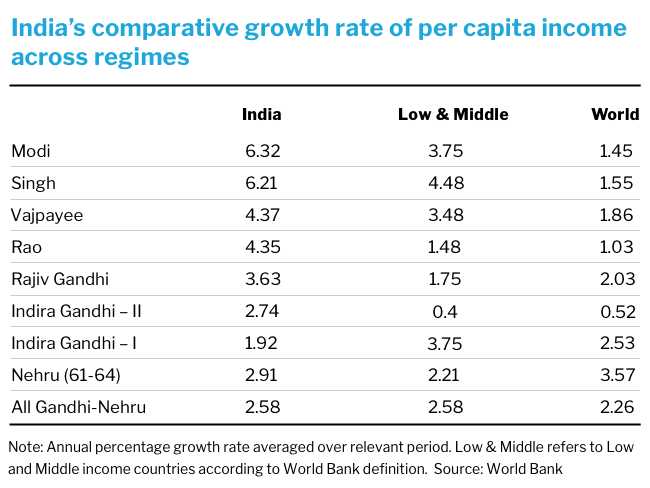

Now some could argue that the growth process in the 1980s led to a balance of payments crisis, with the country being on the verge of default in 1991. That may well be true, but that gets us into a different debate - about the quality of the policies and various extraneous factors like oil prices or global economic condition or weather shocks that influence growth. And if we were to shift goalposts and scrutinize not just the rate of growth, but try to extract the part that the government can take credit for from the part that is due to good or bad luck, then we should do it for all regimes. By that logic, the higher growth rate of India relative to the world or low and middle income countries during the UPA government is even more creditworthy than it appears as it withstood a major global recession and high oil prices. Or, that the higher growth during the Modi government has to be discounted due to favourable oil prices and a change in the methodology of calculating national income that, by all accounts, added at least one percentage point relative to the older method.

If we take a quick and systematic look at the facts, data on comparative growth records of countries provided by the World Bank gives us the following figures relating to India's relative growth performance with respect to the world, or low and middle income countries which are more comparable.

This shows that indeed during the late years of Nehru and the first phase of Indira Gandhi's Prime Ministership, India's growth rate was comparatively lower relative to the world, providing some basis to the question posed to Rahul Gandhi. However, after 1980, the picture changes and if we do an overall comparison, the growth rate of India when a Gandhi or Nehru was a Prime Minister was not in fact lower than the world (or low and middle income countries). None of this takes away from the fact that India's growth since the 1980s was significantly higher than in the earlier era and there is no doubt that the license-control Raj shackled India's growth potential - and as architects of that regime, Indira Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru deserve some of the blame for that.

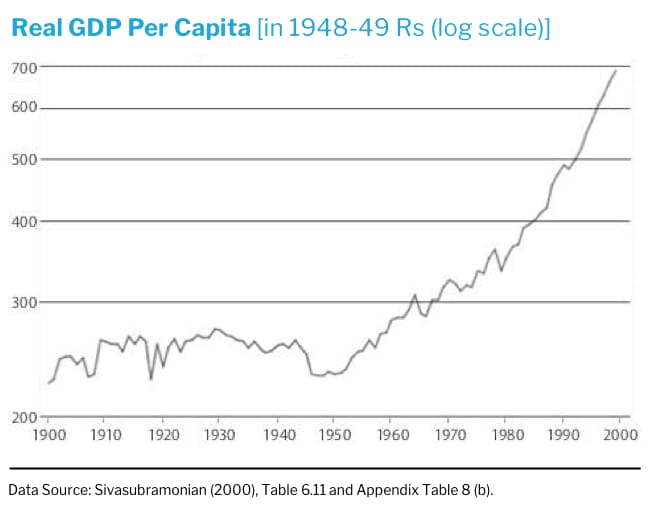

There are data-sources that provide a longer term series of India's per capita income going back to the pre-Independence period but we don't have comparable data for the world or low and middle income countries according to the World Bank definition readily available before 1961. A quick look at such data suggests that the growth rate in the colonial period was virtually close to zero and that there are two statistically significant growth accelerations - one that started after Independence, and the other one that started in the early 80s. Therefore, as much as Nehru deserves some criticism for what used to be referred to as the "Hindu rate of growth" of the 60s, he (and Mahalanobis, the eminent statistician and architect of the Second Five Year plan focusing on infrastructure and heavy industries) deserve some credit for the growth acceleration in the first decade of his premiership.

There are a few lessons to be learnt from this.

First, it important to not let one's political opinions colour one's reading of facts too much. We all have biases or prior views that need to be judged against facts. In this instance, the premise of the question was factually incorrect even though there was a less partisan way of framing the underlying policy critique, which would have had some validity.

Second, a simplistic comparison of growth rates across regimes is not a very meaningful measure of their performance. There are many factors that govern growth and it is possible that the effects of good policies may get eclipsed by adverse exogenous factors, as much as the effects of bad policies may get buffered by favourable ones.

Third, economic policymaking is like a relay race - some of the positive effects of good policies may well benefit future regimes, as one could argue about policies undertaken during the Rao and Vajpayee regimes helping the subsequent regimes of Singh and Modi.

Growth is all about the future while history is about the past. It is important to learn from history but it is also important not to get bogged down in partisan historical debates, in economic or other domains.

(Maitreesh Ghatak is Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics, and earlier taught at the University of Chicago. He writes regularly on economic and political issues with a special focus on India.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.