- Tarun Vijay

Tarun Vijay has been rebuked for suggesting that racism does not now and never has existed in India. One of the interesting assumptions of Mr. Vijay's remarks, for which he has since apologized, is that some Indians are black and others are not. He evidently places himself in the non-black category. Mr. Vijay has doubtless been brushing up on the history of race relations in India since the fracas erupted and he will have come to appreciate the irony of his comments, since there was a time not long ago when many Europeans regarded all Indians as black. They used other racial terms as well, but from the early modern period and into the twentieth century, Europeans frequently referred to Indians as blacks, regardless of complexion. Of course, European writers referred to neither Africans nor Indians exclusively as black and also called numerous other peoples black (in the Americas, for example, or the South Pacific). The very fluidity of the term was what enhanced its appeal to the European observer: the opportunity to generalize about the exotic Orient increased if one was prepared to think of the Ottoman, the Arab, and the Indian as different markers on a continuum of darkness.

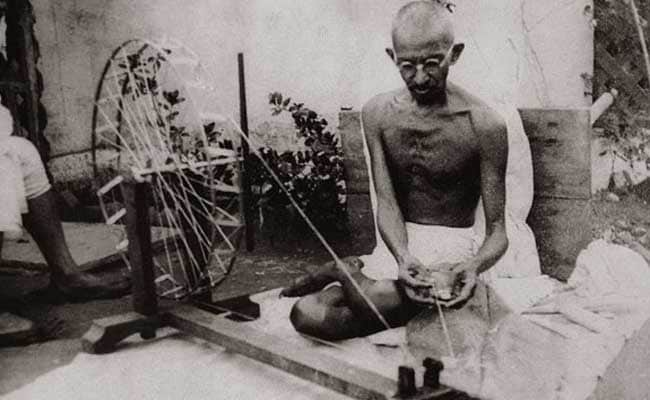

The legacy of this history continues into the present, often in benign ways. Last year, an exhibition on Black History Month at University College London, which likes to claim Gandhi as an alumnus, included the Mahatma in its list of illustrious black students. Nothing sinister was intended: Gandhi was being celebrated as a distinguished black former student. One wonders what Gandhi himself would have made of the honour. His views on race seemed to evolve over time and to move beyond the thoughts he expressed in South Africa, but I would not wheel him out, as Vijay also does, as a spokesperson for enlightened attitudes to race. Perhaps someone ought to have reminded the organizers of the unfortunate remarks about Africans that he uttered in the early phase of his political career.

Last year, an exhibition on Black History Month at University College London included Mahatma Gandhi in its list of illustrious black students

Speculation about the race of Indians continued into the early modern period. In the eighteenth century, Edward Ives wrote about the area around Madras, "The natives on this coast are black but of different shades. Both men and women have long shining black hair, which has not the least tendency to wool like that of the Guinea Negroes. You cannot affront them more, than to call them by the name of negroe, as they conceive it implies an idea of slavery." To Ives, the Indians were black, but simply did not wish to called "negroes" because of the imputation of slavery. We cannot say precisely what term Ives is translating into "negroe", but at least in his representation, Indians are not happy to be compared to African slaves. Large numbers of Ethiopians were, incidentally, brought to India as slaves from the fourteenth century onwards. Ethiopian slaves were imported into India during the Mughal period, and numerous Habshi slaves are attested in Gujarat, Bengal, and the Deccan. Dilawar Khan and Malik Ambar are two of the famous examples, and there were scores of others.

BJP's Tarun Vijay had said, 'If we were racist, would we live with South Indians'

The history of race and race relations in the British colonial period is complicated, but it teaches us that talking about race in a South Asian context, as indeed in other contexts, is a challenging business. Colonial India was the heir to old prejudices based on caste, religion, and ethnic origin as well as racist discourses and practices from Europe. These prejudices and discourses continue to play an unfortunate role in Indian society today. Ask the ambassadors of 44 African countries who formally complained last week that the Indian government had not taken "sufficient and visible deterring measures" to protect Africans in India and who referred to attacks on Africans as "xenophobic and racial".

Phiroze Vasunia is Professor of Greek at University College London and the author, most recently, of 'The Classics and Colonial India' (Oxford, 2013)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.