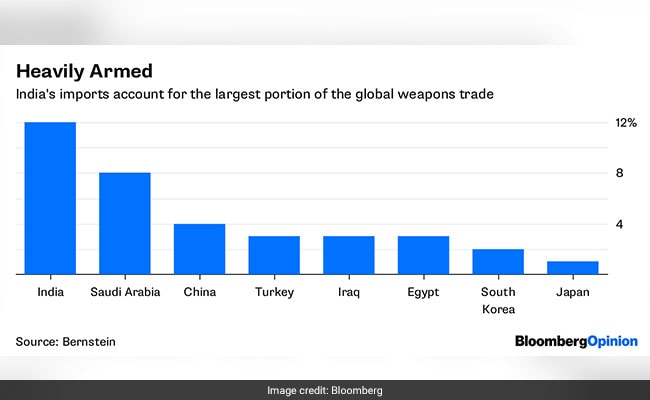

India has been striving toward defense self-sufficiency since the 1960s. The country has one of the world's largest military budgets and also is the top arms importer, buying about 70 percent of its needs abroad. Last year, defense spending rose 5.5 percent to almost $64 billion, data last week showed. Bernstein estimates this could represent a $35 billion opportunity for the private sector.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi deserves credit for a $250 billion military modernization plan. The so-called Make in India program prioritizes defense manufacturing on Indian soil, luring both global heavyweights and domestic firms to bid on (among other things) the biggest-ever order for fighter planes.

A lot stands in the way of these grand plans, however: Much of the ballooning defense budget goes on salaries, chiefly for the army, at the expense of the navy and air force. Capital procurement - essentially, modernization - now accounts for less than 20 percent of total outlays. Meanwhile, red tape discourages Indian companies from investing or staying the course.

Since Modi took office almost four years ago, the government has increasingly leaned on foreign vendors. To lure more of them, the Defense Ministry earlier this month circulated draft rules to recraft its policy on so-called "offsets" - pay-to-play arrangements that help Western defense companies tap international markets, which haven't worked well in India. The latest draft presents vaguely defined offsets, which are controversial and not always successful. In Australia and Japan, for example, the system nurtured inefficiencies in the domestic industry.

Indian and foreign companies obviously hope they'll get a chunk of the business as the policy takes shape. There are billions of dollars of potential contracts for aircraft carriers, destroyers and combat planes. As much as 85 percent of the nation's submarines, and up to 40 percent of its armored vehicles, are nearing the end of their operational life.

A lot of the hope, however, may be just that.

For one thing, incentives aren't aligned. Attracting the private sector is key, as India knows. But without efficiency and focused investments, defense companies face compressed margins. It can take at least three years to bid for an order of defense equipment, and simple tenders don't get enough legitimate bidders.

Meanwhile, changes at the top of the defense ministry have led to some policies that helped private companies being rethought. For instance, Lockheed Martin Corp. set up a strategic partnership with Tata Advanced Systems Ltd. to build fighter jets, but the degree of progress isn't clear, and there's political pressure to reconsider the need for such cooperation.

State-backed companies, like Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd., remain the biggest beneficiaries of military largess. But investors still aren't impressed: Shares of Bharat Electronics Ltd., a pure-play defense communications company backed by the government, have fallen almost 30 percent this year because of shrinking margins and delayed orders. The inefficiencies run deep.

Unless India can address these shortcomings with policies aimed specifically at attracting private-sector investors, its dreams of a defense overhaul face a disappointing reality.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)