Theresa May's Conservatives have emerged once again as the largest party - comfortably ahead of their Labour Party rivals. But far from an endorsement of her eleven months as Prime Minister, the outcome will be seen as a repudiation of both her style and her policies.

Mrs May called this election three years early. She made a catastrophic misjudgement. Her right-wing Conservative Party already had a narrow overall majority in the House of Commons. But she said she needed a clear mandate from the voters to strengthen her hand in negotiations over the details of Britain's withdrawal from the European Union, to give effect to the surprise referendum vote exactly a year ago.

Well, she hasn't been given that clear mandate - indeed she has lost seats. She may manage to limp back into Ten Downing Street by cobbling together deals in a hung Parliament, but the landslide victory which just a month ago seemed almost in her pocket has eluded her.

This was Theresa May's first election as Conservative Party leader and she ran a presidential-style campaign - all about her and the 'strong and stable' government she could deliver.

PM Theresa May has suffered one of the most dramatic reversals in recent British political history, losing an overall majority in parliament in a snap election she had been predicted to win easily

The Conservative Party is brutally unforgiving of leaders who don't deliver the votes. Mrs May's hold on office is slipping away. She certainly won't lead the party into the next general election - and given the messy outcome of this contest, the next election may not be too far away.

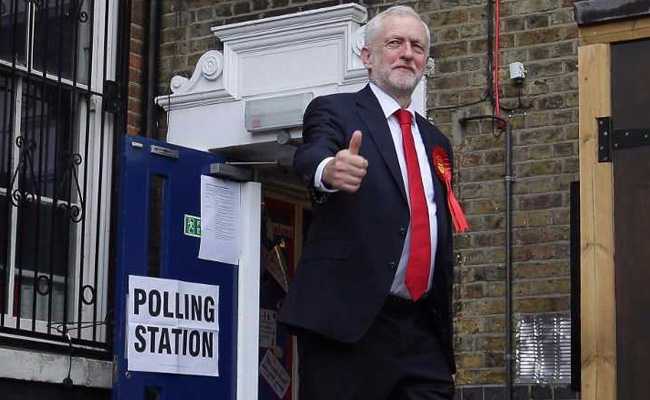

What really tempted Theresa May to stage an early election was the perceived unpopularity of Labour's leader, Jeremy Corbyn. He is by far the most left-wing leader in Labour's history, hugely popular with the party's rank-and-file, but derided by most Labour MPs who believed that turning to the hard left was a recipe for electoral disaster.

But Mr Corbyn has the virtues of transparent honesty and integrity, and as he travelled the country, he attracted thousands to his rallies - and this in a country where the mass political meeting feels a relic of ages past. The young in particular were attracted to his standard - and relished his promises to abolish tuition fees for university students, restore key utilities to state ownership, spend more on the health service and the police, and to tax business and the well-off to fund these policies.

Jeremy Corbyn, a 68-year-old socialist stalwart, has never held major office and began his election campaign as rank outsider

So there's a sharp generational split in political loyalties. More than that, Britain is more polarised between sharp right and hard left (the centre Liberal Democrats polled poorly) than at any time since the 1980s.

Later this month, the Brexit negotiations - about the terms on which Britain leaves the European Union after more than forty-years of membership - are due to start. Theresa May's political authority has been weakened. The 'hard' Brexit which she has championed - embracing withdrawal not only from the political and legal institutions of the EU but the economic single market as well - no longer seems to chime with the British electorate.

There's very unlikely to be any rethink about Britain's withdrawal from the European Union. But rather than slamming the door in the EU's face, it's now more probable that Britain will seek a consensual route towards a new relationship with the country's main trading partners in Europe.

And let's spare a thought for Donald Trump. His shadow hovered over the British election. Many here, and not simply Labour supporters, were horrified by the President's tweets condemning the response of London's mayor to the terrorist attack in the city last weekend in which eight people were killed. The mayor, Sadiq Khan, is Labour by politics, Muslim by religion - and is well-regarded across political boundaries. Mrs May's initial reluctance to repudiate President Trump's remarks caused much dismay.

And Britain's voters, albeit with a confusing overall result, have demonstrated that right-wing populism is falling out of fashion, on this side of the Atlantic at least.

(Andrew Whitehead, a former BBC India correspondent, is honorary professor in politics at the University of Nottingham.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.