There is now a consensus that any political transformation of the Middle East - a long-cherished goal of both U.S. policymakers and millions who live there - will not be achieved by revolution, foreign intervention or civil war. The failure of the Arab Spring, the disastrous consequences of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, and the ongoing catastrophe in Syria have shattered fantasies of sudden change.

It is more fashionable these days to pin hope on demographics and technology - the theory that a massive cohort of young people, armed with smartphones, will succeed where all other efforts have failed.

But we may be overlooking a simpler, surer agent of change: human mortality. Death, especially that of longstanding rulers, has historically been a reliable harbinger of political, economic and social renewal. This is especially true when there's a generational transfer of power - which is exactly what we're about to witness in the Middle East.

There will be four potentially balance-altering funerals in the next few years, as a king, a sultan and two grand ayatollahs reach the end of their mortal coil. The four aging leaders are, in order of their regional influence, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei of Iran, King Salman bin Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani of Iraq and Sultan Qaboos al-Said of Oman. Who succeeds them, and how, will determine the political dynamics of the region for a generation.

Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, supreme leader of Iran

In office since: 1989

Age: 78

Details of the supreme leader's health are a closely guarded secret, but rumors of cancer have persisted for years. One of Tehran's more morbid parlor games involves comparing the latest images of Khamenei with older photos, and speculating about how much time the old man has left. This is often followed by bets over who might succeed him, with hardliners getting the shortest odds and moderates the longest.

On paper, the succession in Tehran ought to be the smoothest of the four: It is the only one where the process is actually laid out on paper. When Khamenei is no longer able to discharge his duties, whether because of ill health or death, his replacement will be selected by the 88 elected members of the Assembly of Experts.

But some of the rules are fungible. The only previous time the process was put into action - when Khamenei replaced the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini - the inconvenient fact that the new man was not qualified as a grand ayatollah was papered over with a fast-tracked "promotion," awarded like some honorary doctorate from an accommodating seminary.

The big question is whether the next supreme leader will be a hardliner like Khamenei, or a relative moderate akin to President Hassan Rouhani. The incumbent has loaded the deck in favor of the conservatives, appointing favorites to top government positions and stacking the assembly. The moderates, always weak, are going through an especially fragile period, with Rouhani having failed to deliver the expected economic windfall of Iran's nuclear deal with the world powers.

Details of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei health are a closely guarded secret.

But accession won't be easy for a hardline candidate, either. Ordinary Iranians are in a sour mood, and the anti-clerical, even anti-Khamenei sloganeering seen in recent street protests across the country indicate a desire for meaningful change at the top. U.S. President Donald Trump's dismantling of the nuclear deal will allow hardliners to rally Iranians behind patriotic slogans for a time, but the economic anxieties behind the protests are bound to deepen with the reimposition of punitive economic sanctions.

Khamenei's departure is also likely to precipitate a power grab by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps. While the corps is officially answerable to the supreme leader, it has grown into an independent military and economic power center. The guards are despised by ordinary Iranians, who see them as symbols of corruption and repression. The commanders know that the quickest way for a new supreme leader to gain legitimacy in the street will be to move against them, and will back the candidate who is most likely to protect their interests.

Arguably the worst outcome possible for political freedom is a compromise candidate who will need to ally with two of the three competing camps - which inevitably means the conservatives and Revolutionary Guards, united in their distrust of the moderates. That, after all, is what worked for Khamenei.

Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud, king of Saudi Arabia

In office since: 2015

Age: 82

King Salman has already upended the succession plan once, when he summarily replaced the previous crown prince, his nephew Mohammed bin Nayef, with his son, Mohammed bin Salman, last summer. In that fell swoop, the king skipped over the claims of an entire generation of Saudi princes: MBS was 31 at the time, and bin Nayef was 57.

MBS has moved aggressively to consolidate his position: He controls most of the levers of state that matter, including the military and the oil sector. He is building credibility outside the kingdom - witness his grand tour of the U.S. earlier this year, during which he talked up an economic and social reform agenda certain to please non-Saudi ears.

But the crown prince is not yet home and dry. His personal prestige continues to take a battering in Yemen, where a Saudi-led war has turned into a quagmire. The Saudi-led blockade of Qatar has failed economically and politically. He has picked pointless fights with allies like Germany and Canada. And a domestic crackdown on women's-rights activists suggests he's facing serious pushback against key elements of his much-touted reforms.

The four aging leaders are in order of their regional influence. (AFP)

None of this is sufficient to cause doubt about his succession, at least not yet. But more resistance lies ahead. Among the domestic forces ranged against him are the skipped-over generation, the conservative clergy and many of the billionaires he fined and imprisoned in a luxury hotel last fall. These overlapping elements have an existential interest in preserving the status quo.

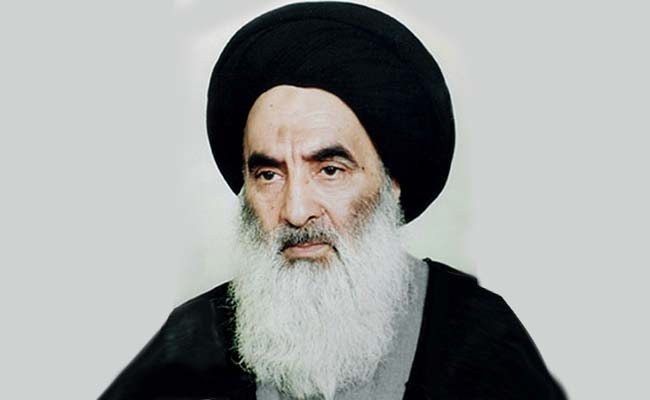

Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, top Shiite cleric in Iraq

In office since: 1992

Age: 87

Iraq's most powerful holy man believes the clergy should not be involved in politics. Not directly, at any rate. But from his seat in the holy city of Najaf he has wielded enormous indirect power by guiding the actions his tens of millions of followers, and for the most part he has been a force for good, promoting democracy and suppressing sectarian impulses. His personal prestige has helped keep Iraq from turning into an Iranian-style theocracy.

The seminaries in Najaf have complex rules and traditions for picking the top cleric, not all of them written, and some still contested between factions. The process could take years to unfold. In normal times the choice would come down to whichever of three other grand ayatollahs outlives him: Muhammed Saeed al-Hakim, Mu¬hammed Ishaq al-Fayadh and Bashir Hussein al-Najafi. But age is against all three - at 76, Najafi is the youngest - and the political conditions in Iraq don't allow for forbearance: Among other things, there is the threat of Iranian influence, not only in Baghdad but also in Najaf.

Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani has wielded enormous indirect power by guiding the actions his tens of millions of followers.

Iran has long sought a louder voice in the holy city as a means to controlling the larger conversation across the Shia world. Tehran was thwarted first by Saddam Hussein, and more recently by Sistani. With the aging cleric out of the way, the Iranians will push for a candidate closer to their own, politically activist school of Shiism.

Yet the succession could also be short-circuited by a low-ranking clergyman who enjoys a mix of religious legacy and political power unprecedented in modern Iraq: Muqtada al-Sadr, whose political faction emerged from the May parliamentary elections with a plurality of seats.

Sadr is not expected to seek the prime ministership himself, but he will be the decisive figure in the government. His own clerical credentials are slim - the 44-year-old is a hojjat-al-islam, a title ranking one rung below that of ayatollah, and a long way down from a grand ayatollah - but many Iraqi Shiites seem willing to look past his lack of learning to his lineage: He is the son and nephew of two powerful, charismatic grand ayatollahs who were murdered by Saddam Hussein.

Sadr has created a political persona as an Iraqi nationalist, railing against both the West and Iran, and a champion of the poor, especially in the urban slums. It helps, too, that he enjoys the loyalty of the vast Mahdi Army, which is equal parts mafia and religious militia.

Sadr has given no indication he aspires to be Sistani's successor; the power he craves is more temporal than spiritual. And in any case, the clerical elite in Najaf is unlikely to pull a Khamenei and award Sadr a quick theological promotion. But he will almost certainly use his political power and militia might to seek a vote, or veto, on who succeeds Sistani.

As with Tehran and Riyadh, Najaf will likely witness a three-way contest to succeed Sistani, between the old-guard traditionalists, Iranian interlopers and Sadr's joker-in-the-pack. The outcome will determine not only the future of Iraqi politics, but the orientation of the larger Shia world.

Qaboos bin Said al-Said, sultan of Oman

In office since: 1970

Age: 77

Some might argue that the sultan doesn't belong on this list because his country has long avoided the social and political turbulence of the region. But if Oman rides smoothly on the choppy waves, it is because of the adroit steering hand of Qaboos. And the question regarding his successor is not only whether he can run the country, but whether he can perform Qaboos's crucial role as moderator in the region's conflicts.

The sultan, who is reported to suffer from colon cancer, has no children of his own, and has assiduously avoided giving so much as a hint about whom he'd like to see follow him on the throne. The succession process in Muscat promises to be the most bizarre of the four: Qaboos is required to nominate the next sultan in a sealed letter, to be opened upon his death - but only if his extended family cannot arrive at a consensus among themselves.

A process so peculiar can hardly be expected to proceed smoothly, and while Qaboos enjoys widespread support among his people, there's also discontent about the state of the economy; scattered street protests have taken place in recent months. Legitimacy bestowed via a sealed envelope is hard to justify, much less sustain, in the 21st century. Like MBS in Saudi Arabia, the next sultan may need to move swiftly to shore up his political position, as well as announce reforms to placate his people.

The temptation is great, at this point, to play that Tehran parlor game, with a region-wide scope. The worst-case (and most likely) scenario will have conservatives and hardliners taking over in Tehran, Riyadh, and Najaf, and a weakling in Muscat. The best case will have Khamenei replaced by a moderate, King MBS proving the reformer he claims to be, Sistani being succeeded by a clone and Oman retaining its peacekeeping role under a new sultan who, if he must emerge from an envelope, then at least has the ability to push it.

It's only a game until you think of the real-life consequences.

(Bobby Ghosh is a columnist and member of the Bloomberg Opinion editorial board. He writes on foreign affairs, with a special focus on the Middle East and the wider Islamic world.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)