Subsequently some of the moral high that the BSP had gained was lost by party leaders training their megaphones on Singh's wife and daughter, who had nothing to do with the matter. While this indicates the loose tongues and misogynistic culture that runs through Uttar Pradesh politics, across parties, what does it suggest in hard political terms?

BJP's Dayashankar Singh had compared BSP leader Mayawati to a prostitute, days after he was made the party's UP Vice President

The controversy triggered by Singh's remarks has consolidated Dalit voters (especially the Jatav community) behind the BSP. This is Mayawati's bedrock. It gave her party a 20 per cent vote share in the 2014 Lok Sabha election, even though the BSP won zero seats. In contrast, the BJP-led alliance won 73 seats of 80.

BSP chief Mayawati waves to supporters at an election rally in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh (File photo)

In 2017, the SP faces an uphill task. By common consensus, Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav has been outmanoeuvred by his "uncles", a euphemism for the brothers, cousins and political associates of his father, Mulayam Singh Yadav, who, like Mulayam himself, remain active in politics and have undercut the chief minister. Further, in cities and towns, the sense that SP-backed criminal syndicates and favoured police officers are collaborating is working to the ruling party's disadvantage.

In the normal course, Mayawati would be expected to capitalise on the anti-incumbency sentiment, present herself as chief ministerial candidate and the only regional alternative of consequence and win. This is what she did in 2007, when the BSP formed the first full-majority government in Uttar Pradesh since 1991. With luck, she could repeat that. Either way, however, conditions are different.

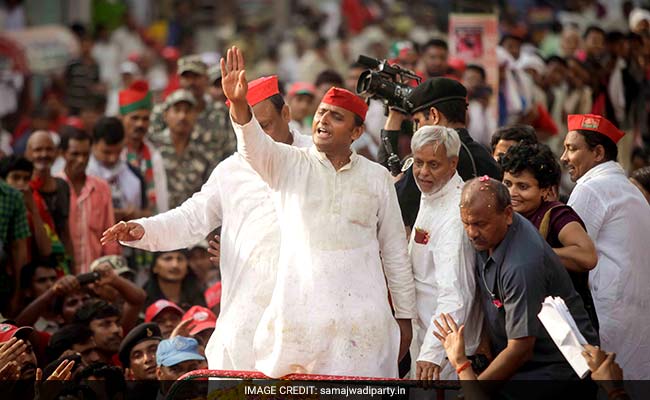

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav leading a roadshow in Varanasi (File photo)

The second contest was between the BSP, with the novel social coalition Mayawati had built, and the SP. Mulayam Singh Yadav lost power and the BSP won 206 seats, more than double the SP's tally. The BJP was reduced to 51 seats, a sizeable segment of its urban and Brahmin voters having migrated to the BSP. It took till 2014 and Narendra Modi for the BJP to recapture those constituencies.

In between, in 2012, Akhilesh Yadav led the SP to victory, winning 224 seats and reducing the BSP to less than half that number. The SP too managed to construct a rainbow coalition, though incremental and bandwagon voters came because of a lack of options and not because the Yadavs assiduously put together a new caste alliance with a political strategy in mind. The BJP remained in the 50 odd seats category and the Congress seat share stayed in the twenties.

BJP president Amit Shah addressing a rally in Uttar Pradesh (File photo)

Indeed, the Dayashankar Singh episode has seen a consolidation of Rajputs behind the BJP, just as Dalits have coalesced that much more vigorously behind the BSP. The feeling that Mayawati's governments tend to be heavy-handed with using Dalit protection laws exists and has a political implication. This is not a value judgement, it is a realistic, cold-blooded assessment of voter perceptions.

What this means is that while Mayawati may well triumph in 2017, her social coalition will need to be different from that in 2007. As such, she is appealing to Muslim voters far more than earlier, promising 100 Muslim candidates (of 403). In theory, a Dalit-Muslim combine is formidable, perhaps unbeatable. Yet, this could mean Mayawati alienating some of those voter groups that were with her in 2007 and 2012. It could also lead to a counter-mobilisation on caste lines and in pockets religious lines.

Congress' chief ministerial candidate Sheila Dikshit began a three-day bus tour to Uttar Pradesh last week

What is the big picture? In 2007 (or even in 2014), it was a case of either the BSP or the BJP taking on the SP, as the party of the lotus and the party of the elephant both targeted key voter groups. In 2017, social alliances are changing. It may well be a BSP versus BJP battle, with the SP pushed down the ladder.

(The author is distinguished fellow, Observer Research Foundation. He can be reached at malikashok@gmail.com)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.