Farooq Abdullah then goes on to say "Just visiting the Pakistan Prime Minister on his birthday does not make any difference." Instead, he stresses, "The Centre has to grapple with the situation in Kashmir" - and adds, "And Pakistan is part of it. You will never have peace here unless we are able to bring Pakistan on board."

He is quite right. We need to talk to Pakistan, and we need to talk to dissident elements in the Valley, not trilaterally, but on parallel bilateral tracks. Indira Gandhi brilliantly perceived this when, in her final one-on-one, face-to-face session with Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in July 1972 at Simla (as it was then spelt), persuaded him to accept that the "issue" of Jammu & Kashmir would be resolved without force and bilaterally. While the Simla Agreement also provided for "other means mutually agreed upon", the emphasis on securing a bilateral resolution of issues effectively took the issue off the international agenda. For 45 years, the international community has largely left it to India and Pakistan to sit together and resolve outstanding matters. But within the past week, we have seen that international patience is wearing thin - so thin that the Indian-origin US Ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, has taken it on herself to publicly caution the two countries that her government will have to intervene unless the two countries engage with each other.

We have learnt from bitter experience that third-country meddling is always only to promote the third country's interests, not the interests of the peoples of India and Pakistan. Pakistan is only too ready to go along with international intervention because her strategic geographical position creates a strong bias in her favour in Western eyes, now underpinned by China's open embrace of Pakistan. So this position of "We won't talk to Pakistan bilaterally and we won't talk to them multilaterally either" is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain. The world will welcome the resumption of dialogue between India and Pakistan, but will not long allow the international fall-out of nuclear-armed India's refusal to engage with its nuclear-armed neighbor. Even more worrying, in this context, is Dr. Abdullah's assertion in his Hindu interview that although Kashmiris earlier agreed with India that "Kashmir has to be resolved bilaterally", in view of the failure to pursue the bilateral path, Kashmiris believe it is time to seek American intervention. Et tu Brute!

If, therefore, our government refuses to engage with Pakistan, it becomes the duty of citizens who do believe in the desirability and possibility of reaching a modus vivendi with Pakistan to keep the conversation going at the level of civil society. I had the privilege of living among the Pakistani people for three years (1978-82), and was much impressed with the abundant goodwill for India that exists among the people at large. I was in daily interaction with hundreds of muhajirs who, day after day, would throng our Consulate-General in Karachi over which I presided. We so organized matters as to issue visas to all but those black-listed on the same evening of the morning they submitted their applications. In the event, I reached the figure of one lakh visas issued within six months of the opening of the Visa Office. One of my proudest moments, perhaps my proudest moment of all, was when I presented a tin of Darjeeling tea to the recipient of the one lakhth visa, and the crowd burst into slogans of "Hindustan ke Consul-General zindabad, zindabad"; "idhar koi rishwat nahin, koi pabandi nahi!"

Of course, it was not all smooth sailing. I also faced down numerous demonstrations, at least one of which turned really ugly, by insisting on talking to the demonstrators instead of shooing them away. I was convinced then, and am convinced even now, that dialogue with Pakistan is not only feasible, but desirable, and could, with mutual respect on both sides, lead to a resolution of even apparently intractable issues. It is a conviction that has only been reinforced by the approximately 35 visits I have made to Pakistan in the 35 years that have lapsed since I was posted back to Delhi. I have never felt insecure in that country. I have always been the recipient of their lavish and warm hospitality. Whatever our differences - and they are legion - one can always talk, and often in a mixture of Hindi and Urdu, to everyone from the aam aadmi and the establishment. Unfortunately, at the official level, what dialogue there has been, has been sporadic, and devoid of continuous, constructive engagement

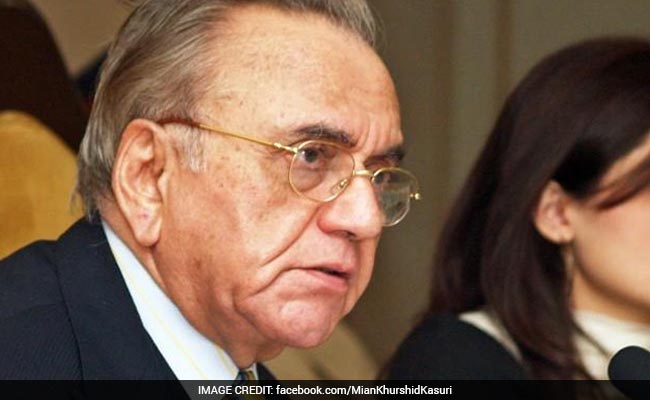

With one major exception, most snatches of dialogue with Pakistan begin with what are called the "low-hanging fruit" such as easing the visa regime or promoting trade. But there was one period, 2003-07, when Vajpayee opened the door and Manmohan Singh walked through it to grapple with the key question of Kashmir, leaving to one side for the moment the so-called "low-hanging fruit". The Pakistani Foreign Minister throughout that time of constructive engagement was Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri.

Former Pakistan Foreign Minister Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri

There was total agreement on two fundamental points: one, that there was no question of an "independent" Kashmir; two, that any solution must not involve any change of borders or exchange of populations, such that the relaxation of intra-state movement of people and goods would ultimately render the Line of Control "irrelevant". Also, barring some drafting changes that were still under negotiation, there was agreement that both political freedoms and economic development on either side of the Line of Control must be balanced and matching, and that an appropriate joint mechanism be devised to harmonize growth in all sectors in both parts of the old Riyasat. Tragically, progress in this meaningful and substantive sense stalled when Musharraf ran into difficulty with his judiciary in early March 2007, just weeks before Dr Manmohan Singh was due to visit Islamabad to unveil the details of the progress made. But that progress was real, and shows what can be achieved through patience, perseverance and persistence - provided the discussion is focused, uninterrupted, uninterruptable and made with solid political backing at the highest level. Critically, progress was possible only because both leaders agreed to not claim unilateral "victory".

As and when (and if) the India-Pakistan dialogue is ever resumed, either the "four-point" Manmohan-Musharraf agreement on J&K could be revived, or similar conclusions to those that took three years to negotiate could be arrived at within three weeks! That is the measure of Khurshid Kasuri's contribution to bettering our mutual relations in even so sensitive an area as Jammu & Kashmir.

It is such a key player in promoting meaningful accommodation between India and Pakistan that the Kolkata-based Centre for Peace and Progress invited to Delhi to engage with similar-minded people on our side of the border. Kasuri, for his part, deliberately scheduled his visit in such a way as to arrive in Delhi on my 76th birthday, 10 April, to join our small family celebration with a few chosen close friends.

When he landed at Delhi airport, the Pakistan High Commission's protocol officer informed him of the news of the death sentence handed out to Kulbhushan Jadhav. Kasuri himself has nothing to do with the apprehension or detention or investigation or prosecution or sentencing of Kulbhushan. He is in an Opposition party and not even elected to the Pakistan National Assembly. He has little or no influence over the ruling party or armed forces. At best, he could listen to the widespread concern in India over Kulbhushan and testify to this concern when he returns to Pakistan. Perhaps the most impassioned voice at our seminar over Kulbhushan's fate was that of the well-known Kashmiri leader, Muzaffar Baig. Others too spoke in a similar vein. The subject was never missing from his discussions with high media personalities, prominent political leaders, and the numerous friends he has made in Delhi over the years. Rather more effectively than has been done by hysterical TV anchors chasing TRPs, the message has been conveyed to a sympathetic senior Pakistani statesman who will pass on the message he has heard to anyone who cares to listen in Pakistan.

I find myself flayed on certain (happily, not all) TV channels for escorting a virtually life-long friend (who has attended all the weddings in my family, and with whom I routinely stay in Lahore) at a time when, to the deep concern of all of us, including Khurshid, sentence has been pronounced on Kulbhushan Jadhav. There is an appeals process - and there will be a petition for clemency to the Pakistan President if the higher appeal process goes against Kulbhushan, as it is likely to. Khurshid will, in his own way, be conveying to his friends and political colleagues in Pakistan the message that has been hammered into him: that the restoration of Kulbhushan to his family would do more to create the right atmosphere for Pakistan and India to engage with each other in dialogue than almost anything else. What else can Khurshid Kasuri, who has contributed so much to the most important development in India-Pakistan relations in 70 years, do when he is no more in office?

As for the Kashmir Valley, Modi has missed his chance by not using the winter spell of snow to start a meaningful conversation with the growing ranks of discontents, ranging in age from children who throw themselves against pellet guns to those of an earlier generation who remember the Maharajah acceding to India. Modi has probably missed the opportunity not by accident but by design. However, if even now, the government were to table a set of proposals for discussion based on an amalgam of documents and commitments covering the distance from the 1952 Delhi Declaration signed by Sheikh Abdullah and Nehru down to the 2007 draft proposals prepared by the distinguished envoys of the Manmohan and Musharraf governments, my thoroughly reliable sources in Kashmir have given me reason to believe that Kashmir might yet be retrieved from the brink of disaster. Alas, there seems to be no one in authority in either Delhi or Srinagar to have the courage or imagination to take the leap to sound sense with either Kashmir or Pakistan.

(Mani Shankar Aiyar is former Congress MP, Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.