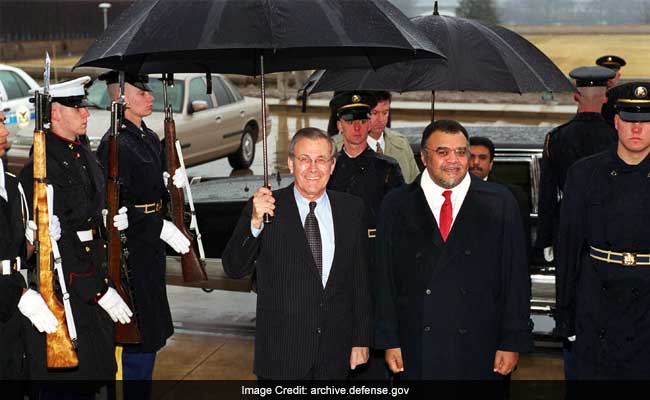

For anyone who remembers Washington in the 1980s and 1990s, the Saudi ambassador at the time was something of a legend. Prince Bandar bin Sultan seemed to know everybody. He was close friends with both Bush presidents and enjoyed warm ties with President Bill Clinton. He often dressed in traditional Saudi garb, but he loved America. He even had his private aircraft painted in the colors of his favorite football team, the Dallas Cowboys.

He was also someone the FBI believed for a time had employed people connected to al-Qaida. This is an important detail in the new chapter of a long-forgotten 2003 congressional report declassified Friday by the U.S. government.

The "28 pages," as this section of the 9/11 report has come to be known, provide no evidence that the Saudi government or Saudi senior officials had planned, financed or even knew ahead of time about 9/11. That remains the conclusion of the 9/11 commission, which examined the leads contained in the 28 pages.

But the declassified chapter does show some connections between Bandar and al-Qaida. To start, it says that the personal phone book of Abu Zubaida, a senior al-Qaida planner who was captured in 2002, contained an unlisted number for the company that managed Bandar's estate in Aspen, Colorado. The CIA later found that there were no "direct links" between other numbers found in Zubaida's phone book and the U.S. numbers. Another number in Abu Zubaida's phone book belonged to a bodyguard employed by the Saudi embassy.

The report also said that another Saudi's phone number was found in an Osama bin Laden safe house in 2002. This person had provided services to a couple who worked as personal assistants to Bandar.

The final tidbit in the declassified chapter involves Bandar's wife, Princess Haifa bint Faisal. She had made regular payments to the wife of Osama Basnam, who the FBI said may have helped two of the 9/11 hijackers when they first came to San Diego in 2000. Bandar himself also wrote a check for Basnam, but this was in 1998 before the hijackers had arrived in America.

It turns out that these leads didn't add up. In a statement released Friday, the two co-chairs of the 9/11 commission, Tom Kean and Lee Hamilton, said, "Although the Commission expressed concerns about multiple individuals, only one employee of the Saudi government was implicated in the Commission's plot investigation."

That person was Fahad al-Thumairy, who was employed by the Saudi Ministry of Islamic Affairs. The FBI and the commission ended up interviewing him in Saudi Arabia. In the end though, the commission said the FBI found no evidence al-Thumairy provided assistance to the two hijackers.

While the 28 pages do not implicate the Saudi government in the 9/11 plot, they do show how the kingdom played a dangerous game in the 1990s when al-Qaida was just getting started. Back then, the small CIA unit that tracked the group observed that the Saudis had stopped cooperating with the agency's monitoring of the group's founder, Osama bin Laden, in 1996 -- in part because he knew too much about the kingdom's involvement with Islamic radicals.

To illustrate Saudi Arabia's non-cooperation, the report says the CIA and FBI for years pressed Riyadh for access to Madani al-Tayyib, who managed bin Laden's finances when he was based in Sudan. But they were persistently rebuffed. As one FBI agent told the Senate investigators, the Saudis would say al-Tayyib was "just a poor man who lost his leg, he doesn't know anything."

Before 9/11, it would have been difficult to see that much was wrong in the U.S.-Saudi relationship. What you saw were Prince Bandar's lavish parties in Washington. What you did not see were the frustrations of the CIA and the FBI, shrouded in the official secrecy of the national security state. You also did not see the few individuals in Bandar's orbit who would come under suspicion after al-Qaida took down the World Trade Center.

(c) 2016, Bloomberg View

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)