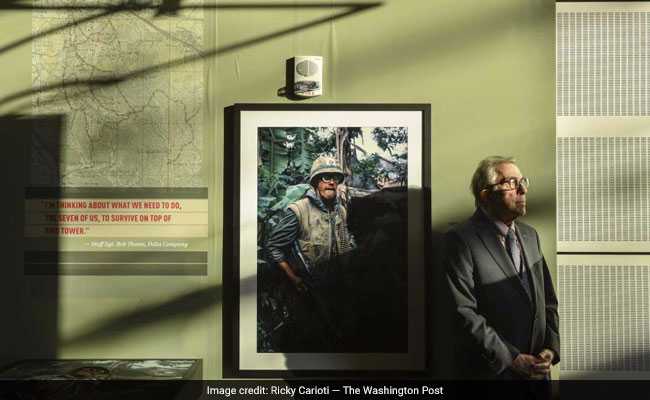

John Olson explains his exhibit of war images from the Tet offensive at the Newseum in Washington, D.C.

Washington:

John Olson can barely remember taking the photograph.

He snapped it, at age 20, during one of the bloodiest battles of the Tet offensive, a series of simultaneous attacks that began Jan. 30, 1968, and led to the most sustained fighting in the Vietnam War.

The picture - the most important he's ever taken - shows a half dozen Marines sprawled atop a mud-crusted tank. One man's arm and eye are bandaged. Blood coats another's leg. In the foreground, a third man lays atop a wooden door his comrades used as a makeshift stretcher. His shirt has been ripped off because, in the center of his chest, is a bullet hole.

Now, 50 years later, Olson's eyes lingered on that image, the centerpiece of "The Marines and Tet," a new exhibit featuring his photographs at the Newseum in downtown Washington, D.C. He adjusted his dark-rimmed glasses and took a deep breath.

"I have next to no memory," Olson said of the iconic moment.

The scene might not stand out, he theorized, because the violence had been unrelenting for hours. Or maybe it was all so ghastly that his mind just blocked some things out.

During the New Year holiday known as Tet, the North Vietnamese orchestrated a barrage of daring assaults throughout South Vietnam. The operation was, in almost every sense, a military failure for America's enemy, who suffered nearly 60,000 casualties, according to estimates. Though that's close to four times the number of U.S. service members killed during that entire year, the North Vietnamese onslaught decimated the American public's already-dwindling support for the war.

"THE VICTORY THAT LED TO DEFEAT," read a 1988 headline in a Washington Post story that summed up the result: "To an already wary America, the shock and dimensions of the attacks created a powerful image - which would never quite be reversed - of loss and endless war."

Olson, now 70, understands that he helped create, through dozens of his haunting photographs, that "powerful image" leading to America's eventual withdrawal in 1973.

He was just 19 when he deployed to Vietnam with the Army, and back then, working for the military publication Stars and Stripes, Olson wanted only to make compelling photographs. And he did - so well, in fact, that Life magazine made him its youngest-ever staff photographer. In the decades that followed, people would often ask if the war affected him, and he'd always tell them that it didn't.

That changed three years ago, when an idea for a project came to him.

Nearly a half-century after taking the pictures that would define his career, he tracked down 10 of the Marines he'd photographed during Tet and interviewed them.

What they told Olson - presented in excerpts as part of the exhibit - shook him.

It's the intimacy of their stories, he said. The devastation that, perhaps, eluded him at an age when he was still too young to buy a beer in many states.

"The whole gun team was in one room," A.B. Grantham, the shirtless Marine atop the tank, told Olson in an interview recorded in 2016. "What we think was a B-40 rocket round came through the hole and hit the back wall."

When Grantham dug his way out of the rubble, he realized that the other three men with him had been wounded with shrapnel. He started to help them outside, but one of the Marines insisted that Grantham first secure their M-60 machine gun so the Viet Cong wouldn't capture it. He picked the weapon up and started to walk out when he glanced to his left.

When Grantham dug his way out of the rubble, he realized that the other three men with him had been wounded with shrapnel. He started to help them outside, but one of the Marines insisted that Grantham first secure their M-60 machine gun so the Viet Cong wouldn't capture it. He picked the weapon up and started to walk out when he glanced to his left.

"There was an NVA soldier kneeling down, aiming right at me," he said in a thick Alabama drawl. "I was looking right down the barrel of the gun."

The bullet struck him in the chest.

He was struggling to breathe, so the Marines with him took cellophane from cigarette packs and stuffed it in his wound before wrapping it in bandages.

"The battle was still raging pretty hard outside," he continued. "I wasn't really paying too much attention because I really thought that I was dying."

They carried him out on the door, then loaded it on the tank. He could hear the engine, smell the diesel.

"When we got back to the triage, someone said, 'This one's not dead yet.' I remember thinking, 'That poor son of a bitch must be hit bad,'" he said. "I didn't know they were talking about me."

Then there's the story of Dong Ba Tower, from the brutal Battle of Hue, as told by former Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms, who was wounded six times during Tet.

He'd been ordered by a captain to hold the tower "at all costs" - even if they had to fight with fixed bayonets. It was the highest point in the area, the battle's single most important position.

He and six other Marines had taken it, and as night fell, they saw what he guessed were 200 North Vietnamese slowly approaching. Through the darkness, he recalled, they could smell the fish sauce, a common condiment, on their enemies' breath.

"We would wait until these guys got right up to the edge of the tower," Thoms said, "and then snatch 'em up and kill 'em."

At 4:30, as dawn approached, the Viet Cong readied an attack.

"One of the guys is telling me, 'Hey, Sarge, we're not going to get out this. We're not going to live through this. You need to pray for us.'"

The only prayer he remembered was "Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep."

"I thought, 'Well, that's not appropriate,'" Thoms recalled, so he asked his men: "How do you talk to God?"

"It'd be like you're talking to a general, Sarge," one of them suggested, so they held hands.

"God, we know we're about to see you in person," he remembered praying. "If we've got to die on this tower, let us die like men and Marines and don't embarrass ourselves, our families or the Marine Corps. Amen."

Moments later, an explosion threw him into the air and down the hillside.

"Literally blown off," he said.

Then Thoms saw the captain again.

"I'm going to give you some more troops," the officer told him. "I need you to go back up and take the tower again."

For Olson, all those hours of research and interviewing have forced him to face his own stories anew, too.

Some details are hazy, like that scene at the tank, but he can still remember taking the photos of Thoms' second charge up the hill, and he can remember what it felt like when news came that the first five men in line had been killed or critically injured.

He can also remember, in the same battle, taking the three consecutive images of one Marine - first writhing, then screaming, then still - that he describes as the "transition from life to death."

And now, when Olson is asked how the Vietnam War affected him, he doesn't know how to answer.

"I don't have all that figured out yet," Olson says, and he's not sure that he ever will.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)

He snapped it, at age 20, during one of the bloodiest battles of the Tet offensive, a series of simultaneous attacks that began Jan. 30, 1968, and led to the most sustained fighting in the Vietnam War.

The picture - the most important he's ever taken - shows a half dozen Marines sprawled atop a mud-crusted tank. One man's arm and eye are bandaged. Blood coats another's leg. In the foreground, a third man lays atop a wooden door his comrades used as a makeshift stretcher. His shirt has been ripped off because, in the center of his chest, is a bullet hole.

Now, 50 years later, Olson's eyes lingered on that image, the centerpiece of "The Marines and Tet," a new exhibit featuring his photographs at the Newseum in downtown Washington, D.C. He adjusted his dark-rimmed glasses and took a deep breath.

"I have next to no memory," Olson said of the iconic moment.

The scene might not stand out, he theorized, because the violence had been unrelenting for hours. Or maybe it was all so ghastly that his mind just blocked some things out.

During the New Year holiday known as Tet, the North Vietnamese orchestrated a barrage of daring assaults throughout South Vietnam. The operation was, in almost every sense, a military failure for America's enemy, who suffered nearly 60,000 casualties, according to estimates. Though that's close to four times the number of U.S. service members killed during that entire year, the North Vietnamese onslaught decimated the American public's already-dwindling support for the war.

"THE VICTORY THAT LED TO DEFEAT," read a 1988 headline in a Washington Post story that summed up the result: "To an already wary America, the shock and dimensions of the attacks created a powerful image - which would never quite be reversed - of loss and endless war."

Olson, now 70, understands that he helped create, through dozens of his haunting photographs, that "powerful image" leading to America's eventual withdrawal in 1973.

He was just 19 when he deployed to Vietnam with the Army, and back then, working for the military publication Stars and Stripes, Olson wanted only to make compelling photographs. And he did - so well, in fact, that Life magazine made him its youngest-ever staff photographer. In the decades that followed, people would often ask if the war affected him, and he'd always tell them that it didn't.

That changed three years ago, when an idea for a project came to him.

Nearly a half-century after taking the pictures that would define his career, he tracked down 10 of the Marines he'd photographed during Tet and interviewed them.

What they told Olson - presented in excerpts as part of the exhibit - shook him.

It's the intimacy of their stories, he said. The devastation that, perhaps, eluded him at an age when he was still too young to buy a beer in many states.

"The whole gun team was in one room," A.B. Grantham, the shirtless Marine atop the tank, told Olson in an interview recorded in 2016. "What we think was a B-40 rocket round came through the hole and hit the back wall."

John Olson stands for a portrait next to one of his images at the Newseum.

"There was an NVA soldier kneeling down, aiming right at me," he said in a thick Alabama drawl. "I was looking right down the barrel of the gun."

The bullet struck him in the chest.

He was struggling to breathe, so the Marines with him took cellophane from cigarette packs and stuffed it in his wound before wrapping it in bandages.

"The battle was still raging pretty hard outside," he continued. "I wasn't really paying too much attention because I really thought that I was dying."

They carried him out on the door, then loaded it on the tank. He could hear the engine, smell the diesel.

"When we got back to the triage, someone said, 'This one's not dead yet.' I remember thinking, 'That poor son of a bitch must be hit bad,'" he said. "I didn't know they were talking about me."

Then there's the story of Dong Ba Tower, from the brutal Battle of Hue, as told by former Staff Sgt. Bob Thoms, who was wounded six times during Tet.

He'd been ordered by a captain to hold the tower "at all costs" - even if they had to fight with fixed bayonets. It was the highest point in the area, the battle's single most important position.

He and six other Marines had taken it, and as night fell, they saw what he guessed were 200 North Vietnamese slowly approaching. Through the darkness, he recalled, they could smell the fish sauce, a common condiment, on their enemies' breath.

"We would wait until these guys got right up to the edge of the tower," Thoms said, "and then snatch 'em up and kill 'em."

At 4:30, as dawn approached, the Viet Cong readied an attack.

"One of the guys is telling me, 'Hey, Sarge, we're not going to get out this. We're not going to live through this. You need to pray for us.'"

The only prayer he remembered was "Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep."

"I thought, 'Well, that's not appropriate,'" Thoms recalled, so he asked his men: "How do you talk to God?"

"It'd be like you're talking to a general, Sarge," one of them suggested, so they held hands.

"God, we know we're about to see you in person," he remembered praying. "If we've got to die on this tower, let us die like men and Marines and don't embarrass ourselves, our families or the Marine Corps. Amen."

Moments later, an explosion threw him into the air and down the hillside.

"Literally blown off," he said.

Then Thoms saw the captain again.

"I'm going to give you some more troops," the officer told him. "I need you to go back up and take the tower again."

For Olson, all those hours of research and interviewing have forced him to face his own stories anew, too.

Some details are hazy, like that scene at the tank, but he can still remember taking the photos of Thoms' second charge up the hill, and he can remember what it felt like when news came that the first five men in line had been killed or critically injured.

He can also remember, in the same battle, taking the three consecutive images of one Marine - first writhing, then screaming, then still - that he describes as the "transition from life to death."

And now, when Olson is asked how the Vietnam War affected him, he doesn't know how to answer.

"I don't have all that figured out yet," Olson says, and he's not sure that he ever will.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world