Eleanor Williams was 18 then, on Dec. 2, 1983, a date that haunts her.

The woman in the bus depot, the perpetrator, was amiable and chatty, Eleanor Williams tearfully told the police.

This was long ago, after Williams, young and naive, had been tragically preyed upon, investigators said. Today, it's a cold case.

The woman, whose crime in the terminal that day shattered Williams' psyche, was African-American and appeared to be in her 20s, Williams recalled, speaking for the first time in decades about a mystery that has perplexed District of Columbia police. Williams said the stranger's perfidy left her so mired in guilt and shame that she later contemplated killing herself.

The woman, about 5-foot-3 and slender, struck up a conversation with Williams in the passenger waiting area, cooing over Williams' infant daughter. After a while, in the sweetest voice, she asked whether she could hold the child.

Please? Just for a minute?

She said her name was Latoya.

Which might have been a lie. Who knows?

She said she was headed "out west" - maybe also a lie.

Williams was 18 then, on Dec. 2, 1983, a date that haunts her. She had grown up on a nine-acre farm in southeast Virginia, and she still lived there. Before that morning, when she set out for Kansas by motor coach with her daughter, she had never ventured more than 30 miles from her home, she said.

Her baby, April Nicole Williams, 3 1/2 months old, was bundled in a pink-and-white snowsuit. The trip's first leg, 200 miles, brought them to a bus station in downtown Washington.

They were scheduled for a three-hour afternoon stop. Carrying April and her diaper bag, Williams, who had been awake since before dawn, trudged into the station and sat down wearily, with 1,200 miles of highway still ahead of her.

Latoya, if that was really her name, "came over next to me at some point and just started talking to me," Williams said recently in her Connecticut apartment, sobbing as she described the awful mistake she made 34 years ago. Latoya "was being friendly, asking me lots of questions. Like, 'Where are you going?' And, 'How old is your baby?' She was nice, you know? Then she was like, 'Do you mind if I hold her?' And I was sitting right next to her, right there, so I said OK, and I let her."

Until lately, Williams, 52, hadn't spoken publicly about her firstborn child since the week in 1983 when her world fell apart. She kept the memories mostly to herself, buried under a weight of sorrow. In her apartment, she shared the story haltingly, pausing for long stretches to gather her composure.

The woman, cradling April, said the baby needed a diaper change, Williams recalled.

"She said: 'Oh, I'll take her to the bathroom. You look tired.' And I was skeptical, like, "Well . . . OK, I guess.' Because I was tired. And I thought about it, but I had already said OK, and she had already got up and taken her to the bathroom.

"And then, I don't know, about 10 minutes later, when she didn't come back, I started getting nervous."

Williams struggles every day to live with this: She entrusted her infant daughter to a stranger in a bus station, some woman. Latoya was her name, or maybe not.

"She went to change her," Williams said, "and I never saw them again."

- - -

"One year ago yesterday a 3-month old girl was kidnapped at the old Trailways bus terminal in downtown Washington, prompting one of the largest and longest manhunts in the city's history. Today, while the chance of the baby's return has decreased, the hope, it seems, has not." - The Washington Post, Dec. 3, 1984.

There's still hope, although very little.

She weighed 11 pounds when she vanished.

Assuming she is alive, she turned 34 last summer.

"I'm pretty sure this is the only cold-case kidnapping we have, the only stranger kidnapping, where we still have a victim out," Washington Police Cmdr. Leslie Parsons, head of the criminal investigations division, said recently. Parsons wouldn't discuss details of the case, but apparently there isn't much to say. "About the only thing we can do proactively at this point is put it out in the media. Hopefully someone will see it, and they'll call us."

When another anniversary of the abduction rolled around in December, the department issued a news release, a standard plea for help: "The infant victim was named April Williams. She has a small birthmark on top of her left wrist in a straight line." The statement was a terse rendition of the basic facts, repeated by police many times through the years, including details from the mother's 1983 recollection of her chat with the kidnapper.

"The suspect could have a sister named Latisha or Natisha," the department said. "The suspect could have the astrological sign of 'Leo.' The suspect is described as [having] . . . a dark brown complexion and spots on her face. Her ears were pierced with two holes in each ear."

It said of Latoya, "she could go by Rene or Rene Latoya."

A few weeks ago, the detective handling the case contacted Williams in Connecticut, where she has lived since 1988, and asked her to speak with the news media. Publicity is good for cold cases, he told her: You shake the tree, and something might fall out. Plus, it's the internet age. The last time Williams talked publicly about April, in the days right after the kidnapping, stories and photos didn't routinely circle the planet as they do now.

Williams balked at sitting for an in-person interview, telling a reporter on the phone that Connecticut was her "safe haven," that she wanted to be left alone there, free of the painful past. She said she has tried for years to block out what happened, to rid her memory of everything about that afternoon except for April's little face.

Then, after a few days, she changed her mind and said OK.

Then, the next morning, she canceled.

Then, later in the week, she phoned and said all right, come to Waterbury.

"Of course I blame myself," she finally said in her apartment. Her hands were trembling. "I blame myself every minute, right up to this minute. It's been 34 years, and it's not something that's over. I deal with it every day, whether I talk about it or not. . . . It's always on my mind. It's always: 'How could you be so stupid? Why? Why did you do it?' "

She lives alone and works as a surgical technician, helping physicians with their instruments in operating rooms. She is "extremely close" to her grown son and daughter, both born after April. She has two grandchildren and hopes for more, she said.

"There were times when I was younger when I wanted to commit suicide, I just felt so bad and so guilty," she said. "But my other kids were always my strength. Like, what would they do if anything ever happened to me? I remember coming home one night after work and thinking, 'I could just drive off the road into a tree, and nobody would ever know that I wanted to do this.' And then I thought about my other kids."

Williams was 4 when her mother died in 1969, on Christmas night. She is the second-youngest of six siblings and was raised by her father on her paternal grandparents' farm near Suffolk, Virginia. In late 1982, when she was a senior in high school, she found out she was pregnant.

"I wasn't happy about it," she recalled. "I mean, I was 17 years old! I didn't want to have a baby. I thought about having an abortion, but I decided not to. . . . There's something about when babies start moving and kicking. You know there's something inside you, and it's like a bonding. It's just some kind of way special."

April was born Aug. 17, 1983, two months after her mother's high school graduation. Williams said the father was a local teenager who wanted no part of parenthood. She saw no future with him, either, and they lost touch after the baby arrived.

By then, Williams was interested in someone else: a soldier in Kansas, a young man she had never seen. One of her brothers was in the Army, stationed at Fort Riley, and he had mentioned his sister Eleanor to a buddy named Kevin. She and Kevin became pen pals during her pregnancy, trading letters and photos for months, and talking by phone.

In November that year, Kevin wired her money for a bus ticket to Kansas so they could meet and spend the holidays together.

Williams had never been out of southeast Virginia.

She made it as far as Washington, where she wound up spending a week, frightened, disoriented, often panicked, with news lights flashing and detectives pressing her, wanting to know this, wanting to know that - then more detectives, asking, asking, demanding.

These were stone-hard questions from stone-hard men with badges, the gist of the queries being: What did you do to her? Tell us. Where is she?

Latoya took her!

And a polygraph examiner, quietly, in a mortician's voice:

"Did you sell your baby?"

At last, when the police seemed satisfied with her story, Williams was gently sent on her way, home to the farm. She said she hasn't set foot in the District since.

"And I never will go back, ever."

- - -

"Mother of Kidnapped Baby Hypnotized" - Post headline, March 10, 1984.

Latoya had short hair, dark and wavy.

She wore green pants and a white ski jacket with a purple floral lining.

Williams told the detectives that.

The Post reported at the time that the woman in the bus station had taken the baby with her to a fast-food counter to buy sodas. This detail showed up in the newspaper repeatedly, but it wasn't accurate, Williams said. She recalled reading it that week. And she said the mistake didn't surprise her because she had learned, in just a few hours' time back then, to never trust anyone she doesn't know: Police, reporters, strangers in bus depots - trust nobody.

"That's how I am now," she said. "I'm always going to be that way."

These days, there would almost certainly be video footage of some Latoya walking into a bus terminal. Security cameras would capture her in the waiting area, would record her chatting up a young mother, then heading to a restroom or wherever, and sneaking out of the station with a tiny bundle in her arms. But the Latoya of 1983 stole a baby in the pre-surveillance age. "If we had images of the suspect," Parsons said, "we'd definitely put them out to the public."

She is a ghost.

Hours after the abduction, the driver of a Metrobus and several passengers reported seeing a woman on the bus who matched the suspect's description. The woman, carrying an infant, got off near the Prince George's County line, the witnesses said. Squads of police officers canvassed the area for days, knocking on doors. But the trail, if it was a trail, went cold.

Deep in Virginia, meanwhile, Williams grew tired of being stared at.

"I just couldn't deal with everybody looking at me and talking about me and having something to say about my situation," she recalled. "It was always, 'She gave her baby away.' People were always whispering that. Or, 'She's just not fit to have a child.' I mean, the way people are, they're cruel; they're mean. Until something happens to them."

A month after the abduction, Williams left the farm for Kansas again on a motor coach.

Emotionally she was immature, still an adolescent, she said.

Kevin, the Fort Riley soldier, was there when she got off the bus.

"All I needed him for was to have a baby to replace April," Williams said. "He knew the only reason for me visiting him was because I wanted to get pregnant again, because I wanted another April. I thought it was going to make me feel better. I thought it would make it hurt less. But actually all it did was make it hurt more."

She soon lost touch with Kevin.

Their daughter was born the following September.

Williams asked that the daughter's name not be published, for privacy's sake. She is 33 and understands the circumstances of her conception. Williams told her the story when she was teenager. She also told her son, born in 1986. The three have had many long conversations about April and the emotional impact of her disappearance, Williams said. She said they are parent, daughter, son, and the best of friends.

And the siblings know that every Aug. 17, they should leave their mother alone.

"I always spend April's birthday by myself," Williams said. "I don't want to be around my other kids, because that's me and April's day. I sit and just think about her, hold onto her picture, cry. And I just wonder what she could be doing."

Her voice was pleading.

"All the stuff they do in school, the awards they get. Did she get any awards? You know, the prom, homecoming, graduation - did she go to the prom? What did she grow up to be? Does she have a career? Does she have kids?"

Williams gazed at the small tabletop in front of her.

"Did she have a wedding? Did she have . . ."

It's pointless, always pointless.

For answers never come.

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

This was long ago, after Williams, young and naive, had been tragically preyed upon, investigators said. Today, it's a cold case.

The woman, whose crime in the terminal that day shattered Williams' psyche, was African-American and appeared to be in her 20s, Williams recalled, speaking for the first time in decades about a mystery that has perplexed District of Columbia police. Williams said the stranger's perfidy left her so mired in guilt and shame that she later contemplated killing herself.

The woman, about 5-foot-3 and slender, struck up a conversation with Williams in the passenger waiting area, cooing over Williams' infant daughter. After a while, in the sweetest voice, she asked whether she could hold the child.

Please? Just for a minute?

She said her name was Latoya.

Which might have been a lie. Who knows?

She said she was headed "out west" - maybe also a lie.

Williams was 18 then, on Dec. 2, 1983, a date that haunts her. She had grown up on a nine-acre farm in southeast Virginia, and she still lived there. Before that morning, when she set out for Kansas by motor coach with her daughter, she had never ventured more than 30 miles from her home, she said.

Her baby, April Nicole Williams, 3 1/2 months old, was bundled in a pink-and-white snowsuit. The trip's first leg, 200 miles, brought them to a bus station in downtown Washington.

They were scheduled for a three-hour afternoon stop. Carrying April and her diaper bag, Williams, who had been awake since before dawn, trudged into the station and sat down wearily, with 1,200 miles of highway still ahead of her.

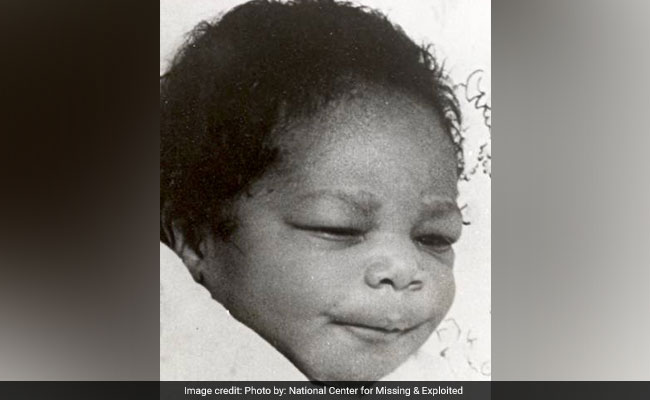

April Nicole Williams was 3 1/2 months old, bundled in a pink-and-white snowsuit when she was kidnapped.

Latoya, if that was really her name, "came over next to me at some point and just started talking to me," Williams said recently in her Connecticut apartment, sobbing as she described the awful mistake she made 34 years ago. Latoya "was being friendly, asking me lots of questions. Like, 'Where are you going?' And, 'How old is your baby?' She was nice, you know? Then she was like, 'Do you mind if I hold her?' And I was sitting right next to her, right there, so I said OK, and I let her."

Until lately, Williams, 52, hadn't spoken publicly about her firstborn child since the week in 1983 when her world fell apart. She kept the memories mostly to herself, buried under a weight of sorrow. In her apartment, she shared the story haltingly, pausing for long stretches to gather her composure.

The woman, cradling April, said the baby needed a diaper change, Williams recalled.

"She said: 'Oh, I'll take her to the bathroom. You look tired.' And I was skeptical, like, "Well . . . OK, I guess.' Because I was tired. And I thought about it, but I had already said OK, and she had already got up and taken her to the bathroom.

"And then, I don't know, about 10 minutes later, when she didn't come back, I started getting nervous."

Williams struggles every day to live with this: She entrusted her infant daughter to a stranger in a bus station, some woman. Latoya was her name, or maybe not.

"She went to change her," Williams said, "and I never saw them again."

- - -

"One year ago yesterday a 3-month old girl was kidnapped at the old Trailways bus terminal in downtown Washington, prompting one of the largest and longest manhunts in the city's history. Today, while the chance of the baby's return has decreased, the hope, it seems, has not." - The Washington Post, Dec. 3, 1984.

There's still hope, although very little.

She weighed 11 pounds when she vanished.

Assuming she is alive, she turned 34 last summer.

"I'm pretty sure this is the only cold-case kidnapping we have, the only stranger kidnapping, where we still have a victim out," Washington Police Cmdr. Leslie Parsons, head of the criminal investigations division, said recently. Parsons wouldn't discuss details of the case, but apparently there isn't much to say. "About the only thing we can do proactively at this point is put it out in the media. Hopefully someone will see it, and they'll call us."

When another anniversary of the abduction rolled around in December, the department issued a news release, a standard plea for help: "The infant victim was named April Williams. She has a small birthmark on top of her left wrist in a straight line." The statement was a terse rendition of the basic facts, repeated by police many times through the years, including details from the mother's 1983 recollection of her chat with the kidnapper.

"The suspect could have a sister named Latisha or Natisha," the department said. "The suspect could have the astrological sign of 'Leo.' The suspect is described as [having] . . . a dark brown complexion and spots on her face. Her ears were pierced with two holes in each ear."

It said of Latoya, "she could go by Rene or Rene Latoya."

A few weeks ago, the detective handling the case contacted Williams in Connecticut, where she has lived since 1988, and asked her to speak with the news media. Publicity is good for cold cases, he told her: You shake the tree, and something might fall out. Plus, it's the internet age. The last time Williams talked publicly about April, in the days right after the kidnapping, stories and photos didn't routinely circle the planet as they do now.

Williams balked at sitting for an in-person interview, telling a reporter on the phone that Connecticut was her "safe haven," that she wanted to be left alone there, free of the painful past. She said she has tried for years to block out what happened, to rid her memory of everything about that afternoon except for April's little face.

Then, after a few days, she changed her mind and said OK.

Then, the next morning, she canceled.

Then, later in the week, she phoned and said all right, come to Waterbury.

"Of course I blame myself," she finally said in her apartment. Her hands were trembling. "I blame myself every minute, right up to this minute. It's been 34 years, and it's not something that's over. I deal with it every day, whether I talk about it or not. . . . It's always on my mind. It's always: 'How could you be so stupid? Why? Why did you do it?' "

She lives alone and works as a surgical technician, helping physicians with their instruments in operating rooms. She is "extremely close" to her grown son and daughter, both born after April. She has two grandchildren and hopes for more, she said.

"There were times when I was younger when I wanted to commit suicide, I just felt so bad and so guilty," she said. "But my other kids were always my strength. Like, what would they do if anything ever happened to me? I remember coming home one night after work and thinking, 'I could just drive off the road into a tree, and nobody would ever know that I wanted to do this.' And then I thought about my other kids."

Williams was 4 when her mother died in 1969, on Christmas night. She is the second-youngest of six siblings and was raised by her father on her paternal grandparents' farm near Suffolk, Virginia. In late 1982, when she was a senior in high school, she found out she was pregnant.

"I wasn't happy about it," she recalled. "I mean, I was 17 years old! I didn't want to have a baby. I thought about having an abortion, but I decided not to. . . . There's something about when babies start moving and kicking. You know there's something inside you, and it's like a bonding. It's just some kind of way special."

April was born Aug. 17, 1983, two months after her mother's high school graduation. Williams said the father was a local teenager who wanted no part of parenthood. She saw no future with him, either, and they lost touch after the baby arrived.

By then, Williams was interested in someone else: a soldier in Kansas, a young man she had never seen. One of her brothers was in the Army, stationed at Fort Riley, and he had mentioned his sister Eleanor to a buddy named Kevin. She and Kevin became pen pals during her pregnancy, trading letters and photos for months, and talking by phone.

In November that year, Kevin wired her money for a bus ticket to Kansas so they could meet and spend the holidays together.

Williams had never been out of southeast Virginia.

She made it as far as Washington, where she wound up spending a week, frightened, disoriented, often panicked, with news lights flashing and detectives pressing her, wanting to know this, wanting to know that - then more detectives, asking, asking, demanding.

These were stone-hard questions from stone-hard men with badges, the gist of the queries being: What did you do to her? Tell us. Where is she?

Latoya took her!

And a polygraph examiner, quietly, in a mortician's voice:

"Did you sell your baby?"

At last, when the police seemed satisfied with her story, Williams was gently sent on her way, home to the farm. She said she hasn't set foot in the District since.

"And I never will go back, ever."

- - -

"Mother of Kidnapped Baby Hypnotized" - Post headline, March 10, 1984.

Latoya had short hair, dark and wavy.

She wore green pants and a white ski jacket with a purple floral lining.

Williams told the detectives that.

The Post reported at the time that the woman in the bus station had taken the baby with her to a fast-food counter to buy sodas. This detail showed up in the newspaper repeatedly, but it wasn't accurate, Williams said. She recalled reading it that week. And she said the mistake didn't surprise her because she had learned, in just a few hours' time back then, to never trust anyone she doesn't know: Police, reporters, strangers in bus depots - trust nobody.

"That's how I am now," she said. "I'm always going to be that way."

These days, there would almost certainly be video footage of some Latoya walking into a bus terminal. Security cameras would capture her in the waiting area, would record her chatting up a young mother, then heading to a restroom or wherever, and sneaking out of the station with a tiny bundle in her arms. But the Latoya of 1983 stole a baby in the pre-surveillance age. "If we had images of the suspect," Parsons said, "we'd definitely put them out to the public."

She is a ghost.

Hours after the abduction, the driver of a Metrobus and several passengers reported seeing a woman on the bus who matched the suspect's description. The woman, carrying an infant, got off near the Prince George's County line, the witnesses said. Squads of police officers canvassed the area for days, knocking on doors. But the trail, if it was a trail, went cold.

Deep in Virginia, meanwhile, Williams grew tired of being stared at.

"I just couldn't deal with everybody looking at me and talking about me and having something to say about my situation," she recalled. "It was always, 'She gave her baby away.' People were always whispering that. Or, 'She's just not fit to have a child.' I mean, the way people are, they're cruel; they're mean. Until something happens to them."

A month after the abduction, Williams left the farm for Kansas again on a motor coach.

Emotionally she was immature, still an adolescent, she said.

Kevin, the Fort Riley soldier, was there when she got off the bus.

"All I needed him for was to have a baby to replace April," Williams said. "He knew the only reason for me visiting him was because I wanted to get pregnant again, because I wanted another April. I thought it was going to make me feel better. I thought it would make it hurt less. But actually all it did was make it hurt more."

She soon lost touch with Kevin.

Their daughter was born the following September.

Williams asked that the daughter's name not be published, for privacy's sake. She is 33 and understands the circumstances of her conception. Williams told her the story when she was teenager. She also told her son, born in 1986. The three have had many long conversations about April and the emotional impact of her disappearance, Williams said. She said they are parent, daughter, son, and the best of friends.

And the siblings know that every Aug. 17, they should leave their mother alone.

"I always spend April's birthday by myself," Williams said. "I don't want to be around my other kids, because that's me and April's day. I sit and just think about her, hold onto her picture, cry. And I just wonder what she could be doing."

Her voice was pleading.

"All the stuff they do in school, the awards they get. Did she get any awards? You know, the prom, homecoming, graduation - did she go to the prom? What did she grow up to be? Does she have a career? Does she have kids?"

Williams gazed at the small tabletop in front of her.

"Did she have a wedding? Did she have . . ."

It's pointless, always pointless.

For answers never come.

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world