West Sayville, New York:

Without doubt, many more people line the sidewalks to see the St. Patrick's Day Parade in Manhattan than to watch the St. Mary Malankara Indian Orthodox Church's annual Assumption Day Parade, which began here on Sunday with the usual blowing of the kumbu horn and the dancing of the koladi by the congregation's teenage girls, dressed in saris and banging sticks.

But the Indians' parade has its longtime devotees: neighborhood residents, mostly, who say they look forward to the procession because it is practically the only time when the people of the congregation venture outside, not counting getting in and out of their cars.

None of St. Mary's 100 or so parishioners live in West Sayville, a predominantly white, middle-class community on Long Island's South Shore where in the last few decades a surfeit of empty church buildings has attracted various religious communities on wheels.

The Indian congregants drive in from Queens, Brooklyn, western Nassau County and even New Jersey and Staten Island, to worship in a former Dutch Reformed Church building they bought in 1992. Inside, they speak Malayalam, the dialect of the Indian province where most have their roots, and they worship according to an Orthodox Christian liturgy that traces its origins to the teachings of the apostle Thomas.

At an hour or more, their road time is longer than the average trip to church, but national surveys show that most Americans travel farther to religious services than they used to, just as they journey farther to work. Except for Orthodox Jews, who are required to do so, hardly anyone walks to a house of worship anymore -- a shift in the landscape that may be best illustrated by the now-unimaginable tableau of Norman Rockwell's 1953 work "Walking to Church."

In West Sayville, the congregation and its parade have assumed a mysterious, almost mythical status, despite the procession's official permit and the three Suffolk County police cars assigned to traffic control.

"If you didn't actually see this with your own eyes, and some people around here haven't, you might think I was making it up," said Christopher Bodkin, a local historian and a former town councilman. "I mean it is so rococo, wonderful, Hindu-esque, with the flower petals, the girls holding the decorative parasols -- everything but the elephants."

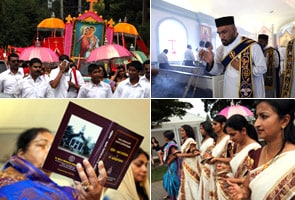

On Sunday, people watched with a mixture of fascination and neighborly nonchalance as the procession made its way around the block, marking the annual observance of Mary's ascent into heaven. At the front was a float with posters of Mary and Thomas and other saints perched on cottony white clouds. Then came the men playing the Indian kumbu horn and chemda drums, the women keeping time with little brass cymbals called Ilathalam, then the littlest girls in angel wings and then the teenagers dancing.

The congregation's women followed behind, pastel-colored saris billowing in the breeze as they flung paper flowers of red and blue. Bringing up the rear was a car carrying the Rev. Paulose Adai, the parish priest, whose plaintive singing of the devotional hymns was greatly amplified from a loudspeaker on the vehicle's roof.

"Usually, they're very quiet people," said Kathy Ahern, a neighbor, shouting to be heard over the din. "I mean, this is the only day we hear anything from them at all." She laughed.

Across the street, some people sat on their porches, glancing occasionally over the tops of their newspapers at the passing parade.

Malankara Christians trace their origins to the first century A.D., when St. Thomas is said to have taken the heavily traveled trade route from the eastern Mediterranean to Kerala, a province on the southwest coast of India where today about 20 percent of the population is Christian. They have had churches in the United States since the early 20th century, but have grown significantly since the 1970s, when immigration policy opened the doors to many nurses trained in the Christian hospitals of Kerala. Nationwide there are about 100 parishes.

Though the churches hew closely to Orthodox Christian liturgy, members also sustain many Indian cultural traditions. Worshipers remove their shoes before entering the church. Men and women sit separately.

And as is still customary in large segments of Indian society, young people accept the notion that their parents will be deeply involved in their selection of a mate.

"It's not, like, 'arranged marriage.' But your parents have to approve of him, and have a meeting with his parents, and you probably wouldn't marry anyone outside your religion," said Judy Geevarghese, 30, who is married to Christopher Geevarghese, 28, whom she met at a cousin's wedding in another St. Mary Malankara parish. They have a daughter, Arianna, 19 months old.

Varghese Poulos, one of the congregation's founders, said church members originally met in a rented basement in Astoria, Queens. Every Sunday, it had to be completely furnished -- from the portable altar to the folding chairs.

Finding out that there was an empty church for sale, even an hour's drive away, was "like a miracle to us," he said.

Mr. Bodkin, the former councilman, suggested there was an oddity in the move: The Indian Orthodox congregation, with its bells and drums, had taken over what was once an outpost of the strictest Calvinist worship.

There is no Dutch Reformed Church in the United States anymore. It has splintered into several new churches. But Jim Stasny, a former pastor of one of those offspring churches in West Sayville, who now lives in Washington, D.C., said he was pleased that someone was putting the building to good use.

"It would be better, perhaps, if they weren't honoring saints, of course -- we don't believe in saints, you know," he said. "But hey, things have changed. We wish those folks well."

But the Indians' parade has its longtime devotees: neighborhood residents, mostly, who say they look forward to the procession because it is practically the only time when the people of the congregation venture outside, not counting getting in and out of their cars.

None of St. Mary's 100 or so parishioners live in West Sayville, a predominantly white, middle-class community on Long Island's South Shore where in the last few decades a surfeit of empty church buildings has attracted various religious communities on wheels.

The Indian congregants drive in from Queens, Brooklyn, western Nassau County and even New Jersey and Staten Island, to worship in a former Dutch Reformed Church building they bought in 1992. Inside, they speak Malayalam, the dialect of the Indian province where most have their roots, and they worship according to an Orthodox Christian liturgy that traces its origins to the teachings of the apostle Thomas.

At an hour or more, their road time is longer than the average trip to church, but national surveys show that most Americans travel farther to religious services than they used to, just as they journey farther to work. Except for Orthodox Jews, who are required to do so, hardly anyone walks to a house of worship anymore -- a shift in the landscape that may be best illustrated by the now-unimaginable tableau of Norman Rockwell's 1953 work "Walking to Church."

In West Sayville, the congregation and its parade have assumed a mysterious, almost mythical status, despite the procession's official permit and the three Suffolk County police cars assigned to traffic control.

"If you didn't actually see this with your own eyes, and some people around here haven't, you might think I was making it up," said Christopher Bodkin, a local historian and a former town councilman. "I mean it is so rococo, wonderful, Hindu-esque, with the flower petals, the girls holding the decorative parasols -- everything but the elephants."

On Sunday, people watched with a mixture of fascination and neighborly nonchalance as the procession made its way around the block, marking the annual observance of Mary's ascent into heaven. At the front was a float with posters of Mary and Thomas and other saints perched on cottony white clouds. Then came the men playing the Indian kumbu horn and chemda drums, the women keeping time with little brass cymbals called Ilathalam, then the littlest girls in angel wings and then the teenagers dancing.

The congregation's women followed behind, pastel-colored saris billowing in the breeze as they flung paper flowers of red and blue. Bringing up the rear was a car carrying the Rev. Paulose Adai, the parish priest, whose plaintive singing of the devotional hymns was greatly amplified from a loudspeaker on the vehicle's roof.

"Usually, they're very quiet people," said Kathy Ahern, a neighbor, shouting to be heard over the din. "I mean, this is the only day we hear anything from them at all." She laughed.

Across the street, some people sat on their porches, glancing occasionally over the tops of their newspapers at the passing parade.

Malankara Christians trace their origins to the first century A.D., when St. Thomas is said to have taken the heavily traveled trade route from the eastern Mediterranean to Kerala, a province on the southwest coast of India where today about 20 percent of the population is Christian. They have had churches in the United States since the early 20th century, but have grown significantly since the 1970s, when immigration policy opened the doors to many nurses trained in the Christian hospitals of Kerala. Nationwide there are about 100 parishes.

Though the churches hew closely to Orthodox Christian liturgy, members also sustain many Indian cultural traditions. Worshipers remove their shoes before entering the church. Men and women sit separately.

And as is still customary in large segments of Indian society, young people accept the notion that their parents will be deeply involved in their selection of a mate.

"It's not, like, 'arranged marriage.' But your parents have to approve of him, and have a meeting with his parents, and you probably wouldn't marry anyone outside your religion," said Judy Geevarghese, 30, who is married to Christopher Geevarghese, 28, whom she met at a cousin's wedding in another St. Mary Malankara parish. They have a daughter, Arianna, 19 months old.

Varghese Poulos, one of the congregation's founders, said church members originally met in a rented basement in Astoria, Queens. Every Sunday, it had to be completely furnished -- from the portable altar to the folding chairs.

Finding out that there was an empty church for sale, even an hour's drive away, was "like a miracle to us," he said.

Mr. Bodkin, the former councilman, suggested there was an oddity in the move: The Indian Orthodox congregation, with its bells and drums, had taken over what was once an outpost of the strictest Calvinist worship.

There is no Dutch Reformed Church in the United States anymore. It has splintered into several new churches. But Jim Stasny, a former pastor of one of those offspring churches in West Sayville, who now lives in Washington, D.C., said he was pleased that someone was putting the building to good use.

"It would be better, perhaps, if they weren't honoring saints, of course -- we don't believe in saints, you know," he said. "But hey, things have changed. We wish those folks well."

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world