Lahore:

The professor was working in his office here on the campus of Pakistan's largest university this month when members of an Islamic student group battered open the door, beat him with metal rods and bashed him over the head with a giant flower pot.

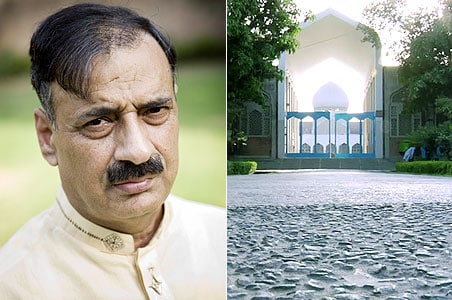

Iftikhar Baloch, an environmental science professor, had expelled members of the group for violent behavior. The retribution left him bloodied and nearly unconscious, and it united his fellow professors, who protested with a nearly three-week strike that ended Monday.

The attack and the anger it provoked have drawn attention to the student group, Islami Jamiat Talaba, whose moral police have for years terrorized this graceful, century-old institution by brandishing a chauvinistic form of Islam, teachers here say.

But the group has help from a surprising source - national political leaders who have given it free rein because they sometimes make political alliances with its parent organization, Jamaat-e-Islami, Pakistan's oldest and most powerful religious party, they say.

The university's plight encapsulates Pakistan's predicament: an intolerant, aggressive minority terrorizes a more open-minded, peaceful majority, while an opportunistic political class dithers, benefiting from alliances with the aggressors.

The dynamic helps explain how the Taliban and other militant groups here, though small and often unpopular minorities, retain their hold over large portions of Pakistani society.

But this is the University of the Punjab, Pakistan's premier institution of higher learning, with about 30,000 students, and a principal avenue of advancement for the swelling ranks of Pakistan's lower and middle classes.

The battle here concerns the future direction of the country, and whether those pushing an intolerant vision of Islam will prevail against this nation's beleaguered, outward-looking, educated class.

That is why the problem of Islami Jamiat Talaba is so urgent, teachers say.

"They are hooligans with a Taliban mentality and they should be banned, full stop," Maliha Aga, a teacher in the art department, said of the student group as she stood in a throng of protesters in professorial robes this month. "That's the only way this university will survive."

The rhetoric of the group, like that of its parent political party, is strongly anti-West, chauvinistic and intolerant of Pakistan's religious minorities. It was a vocal supporter of the Taliban, until doing so became unpopular last year.

Its members block music classes, ban Western soft drinks and beat male students for sitting near girls on the university lawn.

"It's fascist," said Shaista Sirajuddin, an English literature professor, of the Islamic student movement. "Every single government has averted its eyes."

The group is something of a puzzle. It may be aggressive, but it is relatively small, and has waned in popularity among students in recent years. One young teacher said association with it now brought stigma.

But it still manages to dominate by deftly wielding Islam as a weapon to bludgeon its enemies, denouncing anyone who disagrees with it as un-Islamic.

The tactic is effective in Pakistan, a young country whose early confusion about the role of Islam in society has hardened into a rigid certainty, making it highly taboo to question.

"It's unthinkable to talk even about human rights without reference to the Holy Book," said Sirajuddin, referring to the Quran. "Such is the dread to be talked about as un-Islamic."

The reason why goes back to history. In the 1980s, an American-supported autocrat, Mohammad Zia ul-Haq, seeded the education system with Islamists in an effort to forge a unified Pakistani identity. At the University of the Punjab, that created a pool of supporters for Islami Jamiat Talaba among teachers, making the group all but impossible to eject.

It has left liberal teachers like Sirajuddin despairing for their institution, which once upon a time produced three Nobel laureates. Now, they say, it is a shadow of its former self and no longer a safe environment for young people to exchange ideas.

One of the leaders of the group's national chapter, Nadim Ahmed, condemned the beating as "shameful," and said the main attackers had been suspended. But he emphasized that the group itself was peaceful. Its only ambitions, he said, are to welcome new students and organize book fairs.

But students and teachers say the group's aim is power, and that it uses violence to get it. A teacher, who would give her name only as Tayyib, fearing retribution, said group members twice attacked sports events she had organized, once wielding chairs. The recently formed music department has never been able to hold a class on campus.

"Every second issue is a sin," Tayyib said.

The intimidation has poisoned the academic atmosphere, said another young teacher, Nazia, who was also too fearful to allow her full name to be printed. "Jamiat is a threat for teachers," Nazia said. "That weakens the quality of education."

Baloch, the teacher who was beaten on April 1, had taken a stand against them. He identified the ringleader as Usman Ashraf, a 26-year-old geology graduate student, whose mug shot is posted in departments around campus.

"I received many applications" complaining of abuses, he said while convalescing in his home. "And more or less every second one had his name on it."

Just as in Pakistan as a whole, the stakes in this power game are property and money, and the student group has both. It is deeply embedded in the life of the campus, controlling the dormitories, the cafeterias and the campus snack shops.

The group created a parallel administration, according to a former member, Nadim Jamil, and has divided the university into five zones, with a nazim, or mayor, assigned to each. The dormitories are their fiefdoms, he said, where mayors monitor movements, hold Quran reading classes and recruit members.

The university is as ineffectual as the group is organized: There are dormitory ID cards, but no one bothers to check them, said Tayyib, who used to live in the girls' dormitory, which is also controlled by the group.

"It's our fault," Tayyib said. "We are weak. The administration is lethargic."

As unpopular as it may be on campus, the group never has trouble getting recruits. Many first-year students are shy, underprivileged youths from the countryside. The group appeals to this weakness, helping with expenses and opening up a system of benefits: More milk in their tea. Better food. Cleaner dishes.

"It's an addiction," Tayyib said, describing the thinking of the young recruits. "I'm from a remote area, and no one ever listened to me. But now I'm important."

Baloch, who received more than 30 stitches in his head, said he believed that the attack had galvanized public opinion against the group and that it would serve to turn people against it. "The wheels of justice grind slowly but surely," he said.

Others are less certain. Last week, several of the attackers were arrested, but Ashraf, the ringleader, was not among them. Besides, the group's top leader on campus is the son of an important politician.

"This opportunity will be lost," said Nazia, the young teacher. "I know it's pessimistic, but it's what I'm thinking."

Iftikhar Baloch, an environmental science professor, had expelled members of the group for violent behavior. The retribution left him bloodied and nearly unconscious, and it united his fellow professors, who protested with a nearly three-week strike that ended Monday.

The attack and the anger it provoked have drawn attention to the student group, Islami Jamiat Talaba, whose moral police have for years terrorized this graceful, century-old institution by brandishing a chauvinistic form of Islam, teachers here say.

But the group has help from a surprising source - national political leaders who have given it free rein because they sometimes make political alliances with its parent organization, Jamaat-e-Islami, Pakistan's oldest and most powerful religious party, they say.

The university's plight encapsulates Pakistan's predicament: an intolerant, aggressive minority terrorizes a more open-minded, peaceful majority, while an opportunistic political class dithers, benefiting from alliances with the aggressors.

The dynamic helps explain how the Taliban and other militant groups here, though small and often unpopular minorities, retain their hold over large portions of Pakistani society.

But this is the University of the Punjab, Pakistan's premier institution of higher learning, with about 30,000 students, and a principal avenue of advancement for the swelling ranks of Pakistan's lower and middle classes.

The battle here concerns the future direction of the country, and whether those pushing an intolerant vision of Islam will prevail against this nation's beleaguered, outward-looking, educated class.

That is why the problem of Islami Jamiat Talaba is so urgent, teachers say.

"They are hooligans with a Taliban mentality and they should be banned, full stop," Maliha Aga, a teacher in the art department, said of the student group as she stood in a throng of protesters in professorial robes this month. "That's the only way this university will survive."

The rhetoric of the group, like that of its parent political party, is strongly anti-West, chauvinistic and intolerant of Pakistan's religious minorities. It was a vocal supporter of the Taliban, until doing so became unpopular last year.

Its members block music classes, ban Western soft drinks and beat male students for sitting near girls on the university lawn.

"It's fascist," said Shaista Sirajuddin, an English literature professor, of the Islamic student movement. "Every single government has averted its eyes."

The group is something of a puzzle. It may be aggressive, but it is relatively small, and has waned in popularity among students in recent years. One young teacher said association with it now brought stigma.

But it still manages to dominate by deftly wielding Islam as a weapon to bludgeon its enemies, denouncing anyone who disagrees with it as un-Islamic.

The tactic is effective in Pakistan, a young country whose early confusion about the role of Islam in society has hardened into a rigid certainty, making it highly taboo to question.

"It's unthinkable to talk even about human rights without reference to the Holy Book," said Sirajuddin, referring to the Quran. "Such is the dread to be talked about as un-Islamic."

The reason why goes back to history. In the 1980s, an American-supported autocrat, Mohammad Zia ul-Haq, seeded the education system with Islamists in an effort to forge a unified Pakistani identity. At the University of the Punjab, that created a pool of supporters for Islami Jamiat Talaba among teachers, making the group all but impossible to eject.

It has left liberal teachers like Sirajuddin despairing for their institution, which once upon a time produced three Nobel laureates. Now, they say, it is a shadow of its former self and no longer a safe environment for young people to exchange ideas.

One of the leaders of the group's national chapter, Nadim Ahmed, condemned the beating as "shameful," and said the main attackers had been suspended. But he emphasized that the group itself was peaceful. Its only ambitions, he said, are to welcome new students and organize book fairs.

But students and teachers say the group's aim is power, and that it uses violence to get it. A teacher, who would give her name only as Tayyib, fearing retribution, said group members twice attacked sports events she had organized, once wielding chairs. The recently formed music department has never been able to hold a class on campus.

"Every second issue is a sin," Tayyib said.

The intimidation has poisoned the academic atmosphere, said another young teacher, Nazia, who was also too fearful to allow her full name to be printed. "Jamiat is a threat for teachers," Nazia said. "That weakens the quality of education."

Baloch, the teacher who was beaten on April 1, had taken a stand against them. He identified the ringleader as Usman Ashraf, a 26-year-old geology graduate student, whose mug shot is posted in departments around campus.

"I received many applications" complaining of abuses, he said while convalescing in his home. "And more or less every second one had his name on it."

Just as in Pakistan as a whole, the stakes in this power game are property and money, and the student group has both. It is deeply embedded in the life of the campus, controlling the dormitories, the cafeterias and the campus snack shops.

The group created a parallel administration, according to a former member, Nadim Jamil, and has divided the university into five zones, with a nazim, or mayor, assigned to each. The dormitories are their fiefdoms, he said, where mayors monitor movements, hold Quran reading classes and recruit members.

The university is as ineffectual as the group is organized: There are dormitory ID cards, but no one bothers to check them, said Tayyib, who used to live in the girls' dormitory, which is also controlled by the group.

"It's our fault," Tayyib said. "We are weak. The administration is lethargic."

As unpopular as it may be on campus, the group never has trouble getting recruits. Many first-year students are shy, underprivileged youths from the countryside. The group appeals to this weakness, helping with expenses and opening up a system of benefits: More milk in their tea. Better food. Cleaner dishes.

"It's an addiction," Tayyib said, describing the thinking of the young recruits. "I'm from a remote area, and no one ever listened to me. But now I'm important."

Baloch, who received more than 30 stitches in his head, said he believed that the attack had galvanized public opinion against the group and that it would serve to turn people against it. "The wheels of justice grind slowly but surely," he said.

Others are less certain. Last week, several of the attackers were arrested, but Ashraf, the ringleader, was not among them. Besides, the group's top leader on campus is the son of an important politician.

"This opportunity will be lost," said Nazia, the young teacher. "I know it's pessimistic, but it's what I'm thinking."

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world