Denmark topped the list in the first report, in 2012, and again in 2013, but it was displaced by Switzerland last year. (iStock Image)

London:

Denmark has reclaimed its place as the world's happiest country, while Burundi ranks as the least happy nation, according to the fourth World Happiness Report, released Wednesday.

The report found that inequality was strongly associated with unhappiness - a stark finding for rich countries like the United States, where rising disparities in income, wealth, health and well-being have fueled political discontent.

Denmark topped the list in the first report, in 2012, and again in 2013, but it was displaced by Switzerland last year. In this year's ranking, Denmark was back at No. 1, followed by Iceland, Norway, Finland, Canada, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Australia and Sweden. Most are fairly homogeneous nations with strong social safety nets.

At the bottom of the list of more than 150 countries was Burundi, where a violent political crisis broke out last year. Burundi was preceded by Syria, Togo, Afghanistan, Benin, Rwanda, Guinea, Liberia, Tanzania and Madagascar. All of those nations are poor, and many have been destabilized by war, disease or both.

At the bottom of the list of more than 150 countries was Burundi, where a violent political crisis broke out last year. Burundi was preceded by Syria, Togo, Afghanistan, Benin, Rwanda, Guinea, Liberia, Tanzania and Madagascar. All of those nations are poor, and many have been destabilized by war, disease or both.

Of the world's most populous nations, China came in at No. 83, India at No. 118, the United States at No. 13, Indonesia at No. 79, Brazil at No. 17, Pakistan at No. 92, Nigeria at No. 103, Bangladesh at No. 110, Russia at No. 56, Japan at No. 53 and Mexico at No. 21. The United States rose two spots, from No. 15 in 2015.

From 2005 to 2015, Greece saw the largest drop in happiness of any country, a reflection of the economic crisis that began there in 2007.

The happiness ranking was based on individual responses to a global poll conducted by Gallup. The poll included a question, known as the Cantril Ladder: "Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?"

The scholars found that three-quarters of the variation across countries could be explained by six variables: gross domestic product per capita (the rawest measure of a nation's wealth); healthy years of life expectancy; social support (as measured by having someone to count on in times of trouble); trust (as measured by perceived absence of corruption in government and business); perceived freedom to make life choices; and generosity (as measured by donations).

The report was prepared by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, an international panel of social scientists that includes economists, psychologists and public health experts convened by U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.

Though the findings do not represent the formal views of the United Nations, the network is closely tied to the Sustainable Development Goals, which the organization adopted in September aiming, among other things, to end poverty and hunger by 2030, while saving the planet from the most destructive effects of climate change.

The field of happiness research has grown in recent years, but there is significant disagreement about how to measure happiness.

Some scholars find people's subjective assessments of their well-being to be unreliable, and they prefer objective indicators like economic and health data. The scholars behind the World Happiness Report said they tried to take both types of data into account.

In a chapter of the report on the distribution of happiness around the world, three economists - John F. Helliwell, an economist at the University of British Columbia; Haifang Huang of the University of Alberta; and Shun Wang of the Korea Development Institute - argued against a widely held view that changes in people's assessments of their lives are largely transitory. Under this view, people have a baseline level of contentment and rapidly adapt to changing circumstances.

The three economists noted research showing that people's evaluations of their lives "differ significantly and systematically among countries"; that within countries, subgroups differ widely in their levels of happiness; that unemployment and major disabilities have lasting influences on well-being; and that the happiness of migrants approximates that of their new country, instead of their country of origin.

The three economists noted that crises can prompt vastly different responses based on the underlying social fabric. In Greece, where the economy began to plummet in 2007, setting off a crisis in the eurozone that has resulted in three financial bailouts, widespread corruption and mistrust were associated with the diminishing sense of happiness over the past decade.

In contrast, trust and "social capital" are so high in Japan that scholars found, to their surprise, that happiness actually increased in Fukushima, which was devastated by an earthquake and tsunami in 2011, because an outpouring of generosity and cooperation contributed to the community's resilience and rebuilding.

"A crisis imposed on a weak institutional structure can actually further damage the quality of the supporting social fabric if the crisis triggers blame and strife rather than cooperation and repair," the economists wrote. "On the other hand, economic crises and natural disasters can, if the underlying institutions are of sufficient quality, lead to improvements rather than damage to the social fabric."

The report, which was released in Rome, included a chapter analyzing Pope Francis' influential encyclical last year, called "Laudato Si'," or "Praise Be to You," which included a cutting assessment of a world in which continuous technological progress was accompanied by environmental degradation, growing anxieties about the future, and persistent injustice and violence.

Jeffrey D. Sachs, a Columbia University economist who edited the report with Helliwell and Richard Layard of the London School of Economics, praised Pope Francis' admonition against hedonism and consumerism.

He also forcefully rejected the notion that happiness and freedom - especially when narrowly defined as economic liberty - are interchangeable.

"The libertarian argument that economic freedom should be championed above all other values decisively fails the happiness test: There is no evidence that economic freedom per se is a major direct contributor of human well-being above and beyond what it might contribute towards per-capita income and employment," Sachs wrote. "Individual freedom matters for happiness, but among many objectives and values, not to the exclusion of those other considerations."

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

The report found that inequality was strongly associated with unhappiness - a stark finding for rich countries like the United States, where rising disparities in income, wealth, health and well-being have fueled political discontent.

Denmark topped the list in the first report, in 2012, and again in 2013, but it was displaced by Switzerland last year. In this year's ranking, Denmark was back at No. 1, followed by Iceland, Norway, Finland, Canada, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Australia and Sweden. Most are fairly homogeneous nations with strong social safety nets.

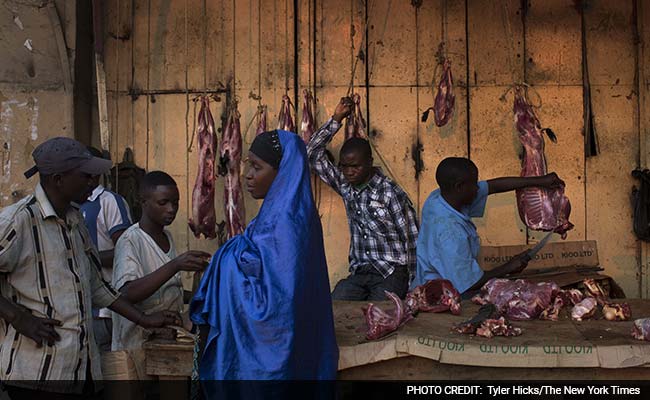

A market in Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi, July 13, 2015. (Tyler Hicks/The New York Times)

Of the world's most populous nations, China came in at No. 83, India at No. 118, the United States at No. 13, Indonesia at No. 79, Brazil at No. 17, Pakistan at No. 92, Nigeria at No. 103, Bangladesh at No. 110, Russia at No. 56, Japan at No. 53 and Mexico at No. 21. The United States rose two spots, from No. 15 in 2015.

From 2005 to 2015, Greece saw the largest drop in happiness of any country, a reflection of the economic crisis that began there in 2007.

The happiness ranking was based on individual responses to a global poll conducted by Gallup. The poll included a question, known as the Cantril Ladder: "Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?"

The scholars found that three-quarters of the variation across countries could be explained by six variables: gross domestic product per capita (the rawest measure of a nation's wealth); healthy years of life expectancy; social support (as measured by having someone to count on in times of trouble); trust (as measured by perceived absence of corruption in government and business); perceived freedom to make life choices; and generosity (as measured by donations).

The report was prepared by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, an international panel of social scientists that includes economists, psychologists and public health experts convened by U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.

Though the findings do not represent the formal views of the United Nations, the network is closely tied to the Sustainable Development Goals, which the organization adopted in September aiming, among other things, to end poverty and hunger by 2030, while saving the planet from the most destructive effects of climate change.

The field of happiness research has grown in recent years, but there is significant disagreement about how to measure happiness.

Some scholars find people's subjective assessments of their well-being to be unreliable, and they prefer objective indicators like economic and health data. The scholars behind the World Happiness Report said they tried to take both types of data into account.

In a chapter of the report on the distribution of happiness around the world, three economists - John F. Helliwell, an economist at the University of British Columbia; Haifang Huang of the University of Alberta; and Shun Wang of the Korea Development Institute - argued against a widely held view that changes in people's assessments of their lives are largely transitory. Under this view, people have a baseline level of contentment and rapidly adapt to changing circumstances.

The three economists noted research showing that people's evaluations of their lives "differ significantly and systematically among countries"; that within countries, subgroups differ widely in their levels of happiness; that unemployment and major disabilities have lasting influences on well-being; and that the happiness of migrants approximates that of their new country, instead of their country of origin.

The three economists noted that crises can prompt vastly different responses based on the underlying social fabric. In Greece, where the economy began to plummet in 2007, setting off a crisis in the eurozone that has resulted in three financial bailouts, widespread corruption and mistrust were associated with the diminishing sense of happiness over the past decade.

In contrast, trust and "social capital" are so high in Japan that scholars found, to their surprise, that happiness actually increased in Fukushima, which was devastated by an earthquake and tsunami in 2011, because an outpouring of generosity and cooperation contributed to the community's resilience and rebuilding.

"A crisis imposed on a weak institutional structure can actually further damage the quality of the supporting social fabric if the crisis triggers blame and strife rather than cooperation and repair," the economists wrote. "On the other hand, economic crises and natural disasters can, if the underlying institutions are of sufficient quality, lead to improvements rather than damage to the social fabric."

The report, which was released in Rome, included a chapter analyzing Pope Francis' influential encyclical last year, called "Laudato Si'," or "Praise Be to You," which included a cutting assessment of a world in which continuous technological progress was accompanied by environmental degradation, growing anxieties about the future, and persistent injustice and violence.

Jeffrey D. Sachs, a Columbia University economist who edited the report with Helliwell and Richard Layard of the London School of Economics, praised Pope Francis' admonition against hedonism and consumerism.

He also forcefully rejected the notion that happiness and freedom - especially when narrowly defined as economic liberty - are interchangeable.

"The libertarian argument that economic freedom should be championed above all other values decisively fails the happiness test: There is no evidence that economic freedom per se is a major direct contributor of human well-being above and beyond what it might contribute towards per-capita income and employment," Sachs wrote. "Individual freedom matters for happiness, but among many objectives and values, not to the exclusion of those other considerations."

© 2016, The New York Times News Service

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world