Li's parents do not believe there can be justice for victims of domestic violence. They've seen the system fail those without connections, they know a conviction can require clout. Refusing to bury their daughter, who was strangled to death, is a bid to make local cadres take notice, to make someone - anyone - care.

In China, as elsewhere, domestic violence is a hidden epidemic - a public health crisis dismissed as private scandal, a crime discounted or covered up.

The state estimates that one in four Chinese women is beaten; experts think the figure is higher and note that statistics often exclude other forms of abuse. Tens of millions are at risk.

A picture of the victim Li Hongxia, and the refrigerator coffin where her dead body lies since February 25th. (Photo for The Washington Post by Giulia Marchi.)

In 2011, Kim Lee, the American wife of a Chinese celebrity, went public with pictures of her battered face and her failed efforts to seek help from police. That a relatively wealthy, foreign woman was turned away reinforced a message Chinese women have heard for years: This is your problem, go home and work it out.

Since coming to power in 2012, the government led by President Xi Jinping has tried to make the issue of domestic violence a cornerstone of its social policy. The country last year passed a first-of-its-kind anti-domestic violence bill. On March 1, just days after Li was killed, it became law.

The bill was hailed as a step in the right direction. Though it does not cover sexual abuse and ignores same-sex partnerships, it includes measures like restraining orders that - if requested and enforced - might have helped Li.

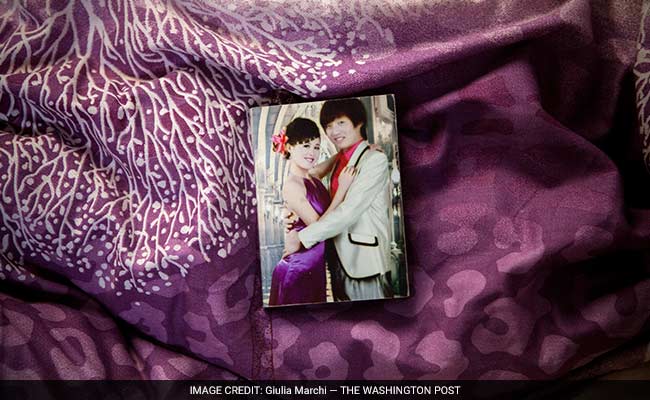

The victim Li Hongxia and her husband Zhang Yazhou in a picture shot for their wedding in 2013. (Photo for The Washington Post by Giulia Marchi.)

In the last year of her life, Li knew she needed help but was told repeatedly to go back to her husband. As she struggled, mostly alone, she faced a system utterly ill-equipped to save her and a society that, for the most part, did not think she needed help.

Li, just 23, knew her husband might kill her. The question for China: Didn't anybody else?

Li was born and raised in Yan Guan, a cluster of homes set among the wheat fields of the Chinese heartland, south of where the Yellow River cuts the northern plain. The second daughter of the Yan family, she spent her first eight years living with a family friend, Li Jinzhong, while her parents raised a son.

The corridor at the Women's and Children's Hospital in Luyi, Henan, where Li Hongxia was strangled by her husband Zhang Yazhou. (Photo for The Washington Post by Giulia Marchi.)

After their wedding, Li moved into his family's home in Zhang village, a 10-minute stroll from Yan Guan. In 2014, they had a daughter. Despite what later happened, neighbors remember the sight of them walking, elbows linked, down rutted, dusty roads.

Interviews with more than a dozen villagers suggest the community saw domestic violence as something that happened often, but to other people. "In this village, everyone has the same surname, so nobody fights here," said the matchmaker, Su Juan.

Yan Jiongjiong cries looking at the pictures of her dead sister pasted on the wall of the couple place in the Zhang village, Henan Province on March 31st, 2016. (Photo for The Washington Post by Giulia Marchi.)

When Li told her mother about the beating, she was advised to work things out at home. Her mother, Duan Liuzhi, said she discouraged her daughter from getting a divorce because ending a marriage might "bring a bad reputation" in town.

For survivors of domestic violence in China, that's a common theme. Though divorce rates are on the rise, women face enormous pressure to get and stay married. And that message is backed by the All-China Women's Federation, the group that's supposed to promote women's rights.

Zhang Tuanjie, young neighbor and friend of the victim's husband Zhang Yazhou, on his bike. Street to the Zhang and Yan villages, Henan Province on March 31st. (Photo for The Washington Post by Giulia Marchi.)

She said Li never came to them. "As a female comrade with a family, you must first behave yourself and do well in your role as a wife, and second, if your husband makes trouble for you, you have to say it," Guo said.

Citing a Chinese expression - "demolishing 10 temples is better that destroying a marriage" - Guo said the federation encourages mediation in most cases of domestic violence. "If he corrects his mistakes, things will be fine."

But things were not fine - and Li began to say so.

In July, she posted online about the beating that led to her back injury, explaining that she initially stayed quiet out of shame. In December, she wrote about her fear of being choked to death - a post that was viewed about 100 times.

Li Hongxia in hospital with a head wound in February 2016. (Courtesy of the Yan family.)

Qi Lianfeng, the lawyer who represented Kim Lee, the American woman battered by her Chinese husband, said Chinese survivors, like women elsewhere, are often told to stay when their life depends on leaving. "Domestic violence often reoccurs," he said, "and is very hard to change."

During the Lunar New Year festival, Zhang and Li welcomed guests to their home for food and drink. When Li said something Zhang did not like, he smashed the back of her head with a stool, Li told her family, an account later confirmed by Zhang Tuanjie, a neighbor who witnessed the assault.

The Zhang family took Li to Luyi County Hospital, where she underwent tests. When her family arrived, the two clans fought in the corridors. Her husband was allowed to visit her room - another legal and moral failure, according to Qi, the lawyer.

After 12 days, Li, who was two months pregnant, was transferred to another, smaller hospital, Luyi Women and Children's Healthcare, for an abortion. On Feb. 25, she texted her husband to say she was hungry. At 5:25 pm, he arrived, according to hospital footage obtained by The Post.

At 5:47 p.m., several nurses walked over to the door, tried the handle, then walked away, even though there was a second, unlocked entrance in an adjoining room, as well as a hall-facing window.

The next day, the hospital offered her shocked parents about $6,000 for her death in their care. They took the cash.

In the halls of the women's and children's hospital, medical staff responded to questions about the case with shrugs, claiming that every person working the day of the murder was at lunch. "Nobody saw him strangle her," said Li Ping, the head of pediatrics.

Shortly after the killing, Zhang Yazhou's family left the village fearing for their lives. Li's family broke into their home and laid Li to rest in the living room, surrounded by wedding pictures and piles of winter clothes.

Her parents and siblings say that they have been left to shoulder Li's funeral and burial expenses and that they've received little support, and considerable harassment, from local officials and police. "Who will help us tend to this?" asked Li's mother, Duan Lizhi. "Nobody came to help."

In late April, nearly two months after the murder, Zhang Yazhou's parents returned to the village to negotiate with the Yans. They have yet to reach an agreement or bury the body.

Zhang Yazhou is in police custody and was not available for comment. In a recent interview with Henan Television, a Party-controlled station, he admitted to the May and February beatings, but said Li's death was an "impulsive" mistake.

"We were fighting and I accidentally killed her," he told the camera.

At the Luyi County police station, the lead investigator declined to comment, referring The Post to county-level propaganda officials, who in turn said to contact the provincial propaganda department. Reached by phone, provincial officials said they did not have jurisdiction.

Asked how Li might have been protected, her life spared, Guo Yanfang, the head of the local branch of the Women's Federation, said she was not sure.

"How could she have been protected? How should I know?"

© 2016 The Washington Post

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world