Mark Zuckerberg's hearings centered on the digital information Facebook built up to serve targeted ads

No one at Google envied Mark Zuckerberg last week as he was being grilled by Congress. But for years, they certainly coveted the personal data that made Facebook Inc. a formidable digital ad player. And the strategies they set to compete have now placed Google squarely in the cross hairs of a privacy backlash against the world's largest social-media company.

The House and Senate questioned Zuckerberg for about 10 hours after revelations that data on millions of Facebook users got into the hands of Cambridge Analytica, a consulting firm that worked on President Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign. The hearings centered on the digital information and machinery Facebook built up to serve targeted ads. No company has a bigger business doing that -- except Google. When the grilling ended, Democrats and some Republicans called for broad privacy regulation, putting Google on the hot seat next to Zuckerberg.

"Google, in every respect, collects more data. Google, in every respect, has a much bigger advertising business," said David Chavern, president of News Media Alliance, a publisher trade group. Rather than "a Facebook privacy law," he expects regulation to target the entire industry.

Tech giants see a higher chance of legislation if Democrats win the House of Representatives or even the Senate later this year. At that point, the companies would have to begin haggling to fend off some proposals that would be intolerable, according to a top policy official at a major internet company. One concern is that proposals will require letting users opt out of data collection completely, the person said, describing that as an untouchable foundation of internet business models.

So far, Alphabet Inc.'s Google has suffered fewer of the problems plaguing Facebook, including fake news and Russian-linked political spending. And it's avoided public blunders like the Cambridge Analytica data leak.

But two years ago, Google altered its offerings in a way that makes it more vulnerable to data-sharing scrutiny. Advertisers using its DoubleClick system to target and measure ads could start anonymously combining web-tracking data (from "cookies" that follow users online) with potent Google information including search queries, location history, phone numbers and credit card information. Until then, Google had steadfastly kept that data separate.

A Google spokeswoman said consumer card data isn't used for ad personalization. Through partnerships with outside firms, Google can use anonymous, encrypted information on about 70 percent of credit and debit card transactions in the U.S. to show advertisers whether their Search and Google Shopping ads resulted in store sales. Marketers don't have direct access to Google user data, and the company forbids advertisers from collecting and sharing personally identifiable information. Google also introduced a website that shows users what information the company collects on them, such as location and device data, and lets them opt out of targeted ads. At the time, Google said the new approach let marketers more easily track consumers across multiple devices. But two former Google ad executives said Facebook's aggressive ad targeting moves also prompted the decision. They asked not to be named discussing their former employer.

At the time, Google said the new approach let marketers more easily track consumers across multiple devices. But two former Google ad executives said Facebook's aggressive ad targeting moves also prompted the decision. They asked not to be named discussing their former employer.

Even before that, Google was working to counter Facebook's critical edge: Knowing exactly who people are online. In 2015, the search giant unveiled Customer Match, a tool letting advertisers target ads using consumers' Gmail addresses. That mirrored a popular Facebook offering called Custom Audiences. Google Plus, the company's social network, failed to catch on with users but did prompt millions of people to log in to Google's other web properties, catnip for marketers. Those changes helped Google's display ad business blossom. Morgan Stanley recently pegged its value at $36 billion. Political advertisers are among those embracing DoubleClick. Last year, the unit touted a case study with i360, a marketing firm affiliated with the conservative power brokers Charles and David Koch. i360 uses its own data to slice online populations into segments, such as those for and against gun control and traditional marriage. A Google blog post explained how DoubleClick's systems sucked in that information to help i360 boost the number of its ads people saw. i360 didn't respond to a request for comment.

Google stresses its ad targeting is anonymous, with strict privacy controls in place. "More than any tech company out there, Google is taking this extremely seriously," said Mario Schiappacasse, who runs display advertising for digital marketing firm Jellyfish. "We've always seen them be extremely cautious."

The ad industry is also quick to point out that the Cambridge Analytica saga is different than the ad targeting Google offers. And the tracking and data-collection methods used by the largest internet services are disclosed in terms and conditions.

But during Zuckerberg's marathon questioning on Capitol Hill, politicians were either oblivious or unconcerned with the distinction. Senators Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat, and John Kennedy, a Republican, introduced consumer privacy legislation last week, writing that tech companies are "profiting off the data of Americans-their online behavior, personal messages, contact and personal information, and more-all while leaving consumers in the dark."

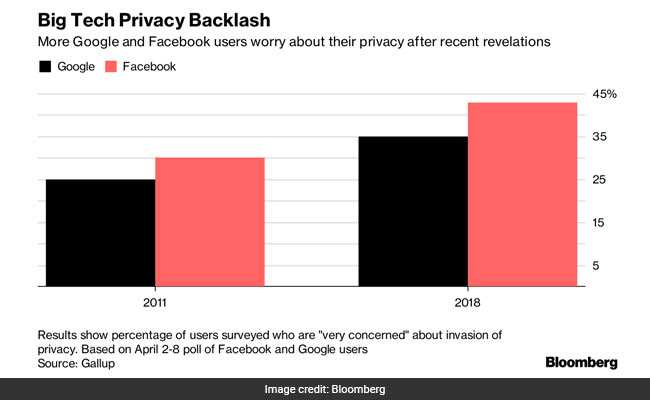

The nuances of complex ad technology and voluminous user agreements are lost on most of the public, too. A recent Gallup poll found that 35 percent of Google users are very concerned about invasion of privacy, up from 25 percent in 2011. Facebook users are even more skeptical: 43 percent of the social network's users surveyed cited the same worry. However, the research also showed Google users are slightly more concerned that their personal data will be sold to or used by other companies.

Google is already buttoning up its data policies in anticipation of Europe's General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, which kicks in next month. The company restricted the number of third-party companies that can serve and track ads through its advertising exchange and on YouTube. Google is also requiring publishers to get user consent for targeted ads to comply with GDPR.

Congress is considering a bipartisan bill, the Honest Ads Act, that would require disclosures for online political ads. Facebook endorsed it and Zuckerberg told Congress he was open to additional regulation. Google has not yet endorsed the bill.

"Of course it's coming," Gary Shapiro, president of the Consumer Technology Association, said about industry regulation. "It's just a question of when."

The House and Senate questioned Zuckerberg for about 10 hours after revelations that data on millions of Facebook users got into the hands of Cambridge Analytica, a consulting firm that worked on President Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign. The hearings centered on the digital information and machinery Facebook built up to serve targeted ads. No company has a bigger business doing that -- except Google. When the grilling ended, Democrats and some Republicans called for broad privacy regulation, putting Google on the hot seat next to Zuckerberg.

"Google, in every respect, collects more data. Google, in every respect, has a much bigger advertising business," said David Chavern, president of News Media Alliance, a publisher trade group. Rather than "a Facebook privacy law," he expects regulation to target the entire industry.

Tech giants see a higher chance of legislation if Democrats win the House of Representatives or even the Senate later this year. At that point, the companies would have to begin haggling to fend off some proposals that would be intolerable, according to a top policy official at a major internet company. One concern is that proposals will require letting users opt out of data collection completely, the person said, describing that as an untouchable foundation of internet business models.

So far, Alphabet Inc.'s Google has suffered fewer of the problems plaguing Facebook, including fake news and Russian-linked political spending. And it's avoided public blunders like the Cambridge Analytica data leak.

But two years ago, Google altered its offerings in a way that makes it more vulnerable to data-sharing scrutiny. Advertisers using its DoubleClick system to target and measure ads could start anonymously combining web-tracking data (from "cookies" that follow users online) with potent Google information including search queries, location history, phone numbers and credit card information. Until then, Google had steadfastly kept that data separate.

A Google spokeswoman said consumer card data isn't used for ad personalization. Through partnerships with outside firms, Google can use anonymous, encrypted information on about 70 percent of credit and debit card transactions in the U.S. to show advertisers whether their Search and Google Shopping ads resulted in store sales. Marketers don't have direct access to Google user data, and the company forbids advertisers from collecting and sharing personally identifiable information. Google also introduced a website that shows users what information the company collects on them, such as location and device data, and lets them opt out of targeted ads.

Data shows an increase in the number of people worried about a breach of privacy from 2011 to 2018

Even before that, Google was working to counter Facebook's critical edge: Knowing exactly who people are online. In 2015, the search giant unveiled Customer Match, a tool letting advertisers target ads using consumers' Gmail addresses. That mirrored a popular Facebook offering called Custom Audiences. Google Plus, the company's social network, failed to catch on with users but did prompt millions of people to log in to Google's other web properties, catnip for marketers. Those changes helped Google's display ad business blossom. Morgan Stanley recently pegged its value at $36 billion. Political advertisers are among those embracing DoubleClick. Last year, the unit touted a case study with i360, a marketing firm affiliated with the conservative power brokers Charles and David Koch. i360 uses its own data to slice online populations into segments, such as those for and against gun control and traditional marriage. A Google blog post explained how DoubleClick's systems sucked in that information to help i360 boost the number of its ads people saw. i360 didn't respond to a request for comment.

Google stresses its ad targeting is anonymous, with strict privacy controls in place. "More than any tech company out there, Google is taking this extremely seriously," said Mario Schiappacasse, who runs display advertising for digital marketing firm Jellyfish. "We've always seen them be extremely cautious."

The ad industry is also quick to point out that the Cambridge Analytica saga is different than the ad targeting Google offers. And the tracking and data-collection methods used by the largest internet services are disclosed in terms and conditions.

But during Zuckerberg's marathon questioning on Capitol Hill, politicians were either oblivious or unconcerned with the distinction. Senators Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat, and John Kennedy, a Republican, introduced consumer privacy legislation last week, writing that tech companies are "profiting off the data of Americans-their online behavior, personal messages, contact and personal information, and more-all while leaving consumers in the dark."

The nuances of complex ad technology and voluminous user agreements are lost on most of the public, too. A recent Gallup poll found that 35 percent of Google users are very concerned about invasion of privacy, up from 25 percent in 2011. Facebook users are even more skeptical: 43 percent of the social network's users surveyed cited the same worry. However, the research also showed Google users are slightly more concerned that their personal data will be sold to or used by other companies.

Google is already buttoning up its data policies in anticipation of Europe's General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, which kicks in next month. The company restricted the number of third-party companies that can serve and track ads through its advertising exchange and on YouTube. Google is also requiring publishers to get user consent for targeted ads to comply with GDPR.

Congress is considering a bipartisan bill, the Honest Ads Act, that would require disclosures for online political ads. Facebook endorsed it and Zuckerberg told Congress he was open to additional regulation. Google has not yet endorsed the bill.

"Of course it's coming," Gary Shapiro, president of the Consumer Technology Association, said about industry regulation. "It's just a question of when."

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world