Corvallis, Oregon:

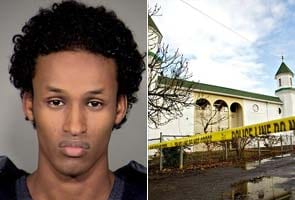

Mohamed Osman Mohamud had seemed to be a well-adjusted American teenager: a solid student whose interests included basketball, girls and the night life at Oregon State University, where he studied engineering.

But those who know him say he changed in recent months. He dropped out of school and stopped attending mosque. And, perhaps most telling, he began lying about his plans for the future.

"He seemed to be in a state of confusion," said Yosof Wanly, the imam at the Salman Al-Farisi Islamic Center in Corvallis, which Mr. Mohamud attended while at college. "He would say things that weren't true. 'I'm going to go get married,' for example. But he wasn't getting married."

A possible explanation for his erratic behavior came as Mr. Mohamud, a 19-year-old naturalized American citizen from Somalia, was arrested Friday by federal agents and charged with plotting to set off a bomb at a Christmas-tree-lighting ceremony in downtown Portland.

The device the authorities say Mr. Mohamud sought to detonate was a fake bomb supplied by Federal Bureau of Investigation agents who had orchestrated a sting operation. But the effect of the planned attack was still felt Sunday, including at the Islamic center here, which was the target of a firebomb early in the day.

No one was injured, but federal agents were here later in the day, investigating a possible link to Mr. Mohamud's arrest, even as Mr. Wanly tried to calm his mosque members' nerves.

Mr. Mohamud is scheduled to appear in federal court in Portland on Monday on a charge of attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction.

Many questions remain about the extent of Mr. Mohamud's connections to Islamic extremists, whom investigators say he wrote to and plotted with, as well as about the apparent contradictions in his personal life, as a studious, friendly teenager and a young man seeking to wage jihad within his adopted country.

"When you think of someone doing what he did, you think of some crazy kind of guy," said Mohamed Kassim, 21, a fellow Oregon State student who knew Mr. Mohamud from around campus. "He wasn't like that. He was just like everybody else."

Many Muslims in Oregon worried that they would face a backlash. And on Sunday, local Muslim leaders emphasized that the case was an isolated incident.

"If this kid's being radicalized, it's not from the locals," said Jesse Day, a spokesman for the Islamic Center of Portland and Masjed As-Saber, where Mr. Mohamud sometimes worshiped.

The president of the center, Imtiaz Khan, shared that concern, and said in an interview that he worried that the mosque and Islam in general would be portrayed unfairly because of the arrest. On Sunday morning, a Portland police car was parked outside the mosque.

"We have women and children here that we want to protect," Mr. Khan said.

But a sense of suspicion and worry prevailed.

Mr. Khan and Mr. Day said several people who worship at the mosque said that F.B.I. agents had knocked on their doors late at night on the day of Mr. Mohamud's arrest, but that none had agreed to speak to the agents.

"People were finding cards in the doors that said F.B.I.," Mr. Day said.

The mosque, the largest in Portland, has been at the center of controversy before. In 2002, the mosque's imam, Sheik Mohamed Abdirahman Kariye, also a naturalized American citizen from Somalia, was arrested at Portland International Airport.

Prosecutors said that trace elements of TNT were found in his luggage, though those tests were later said to be inconclusive and he was not convicted of any crime.

Mr. Kariye did not immediately respond to a request for comment made through Mr. Day, but Mr. Khan repeated that Mr. Mohamud's actions were his own.

"Whatever this event is, it has nothing to do with the mosque," Mr. Khan said.

Mr. Mohamud, his younger sister and their parents had long lived in the Portland area, including in Beaverton, a suburb that has a small Somali population.

Mr. Mohamud's family fled Somalia in the early 1990s, and his father, Osman Barre, a well-educated engineer, worked to establish them in Oregon.

Osman was very sophisticated," said Chris Oace, a former refugee worker for Ecumenical Ministries of Oregon who helped the family resettle here in the early 1990s. "Some refugees are afraid of having Christian churches help them. But it wasn't an issue with his family at all."

Stephanie Napier, a former neighbor, said that the family had been quiet but friendly and that Mr. Mohamud's mother was fiercely proud of her only son.

"He seemed like a great kid," she said. "His mother spoke very highly of him. He always did what he was told and got great grades."

At some point over the last year or so, however, Mr. Mohamud's parents separated, and tensions grew in the family.

A friend of the family said Mr. Barre, who eventually became an engineer for Intel, could be temperamental.

Several people who said they knew Mr. Mohamud's family said they believed that his parents had reported him to law enforcement authorities, citing concerns that his views were becoming extreme. Those people refused to be quoted by name.

A law enforcement official, who was not authorized to publicly discuss certain aspects of the case, said investigators first became aware of Mr. Mohamud because of what the official said were his efforts to connect with Islamic extremists through e-mail.

Soon after that they received information from Mr. Mohamud's father, alerting them to what the official described as increased radicalization. According to the federal affidavit for his arrest, Mr. Mohamud at one point wrote in an e-mail that he felt "betrayed" by his family.

Law enforcement officials also confirmed that his parents had marital problems, but said they were irrelevant to the investigation.

Family members could not be reached for comment.

Cawo Abdi, a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota who studies Somali youth, said some young Somali men in the United States struggle to find a sense of belonging.

"They are trying to find somewhere they can fit in," Ms. Abdi said. "This has led some to join gangs, while others are lured by the Jihadist Web sites and YouTube videos on the Internet."

But for those who knew Mr. Mohamud in Corvallis, a liberal college town whose engineering program draws a sizable number of international students, assimilation did not seem to be the problem.

Mr. Kassim, the Oregon State student, said that Mr. Mohamud seemed to be a normal student, playing basketball at the recreation center, talking about girls and obsessing about the Portland Trailblazers, his favorite team.

On Sunday, such trivial concerns had been replaced by more pressing issues.

Outside the Corvallis mosque, a steady stream of well-wishers -- both Muslim and non-Muslim -- arrived during the day. At the rear of the unmarked structure, a charred and broken window was boarded up. Mosque members said there had been extensive damage, including burned Korans, wedding and death certificates, and other items.

Mohamed Alyajouri, 31, who is married and has three children, said he was in shock when he heard of Mr. Mohamud's arrest and was concerned about the effect on Muslims everywhere.

"This kid had friends here, went to school here," Mr. Alyajouri said. "It's so stupid. Nobody I know thinks that way. But we have to deal with this now."

But those who know him say he changed in recent months. He dropped out of school and stopped attending mosque. And, perhaps most telling, he began lying about his plans for the future.

"He seemed to be in a state of confusion," said Yosof Wanly, the imam at the Salman Al-Farisi Islamic Center in Corvallis, which Mr. Mohamud attended while at college. "He would say things that weren't true. 'I'm going to go get married,' for example. But he wasn't getting married."

A possible explanation for his erratic behavior came as Mr. Mohamud, a 19-year-old naturalized American citizen from Somalia, was arrested Friday by federal agents and charged with plotting to set off a bomb at a Christmas-tree-lighting ceremony in downtown Portland.

The device the authorities say Mr. Mohamud sought to detonate was a fake bomb supplied by Federal Bureau of Investigation agents who had orchestrated a sting operation. But the effect of the planned attack was still felt Sunday, including at the Islamic center here, which was the target of a firebomb early in the day.

No one was injured, but federal agents were here later in the day, investigating a possible link to Mr. Mohamud's arrest, even as Mr. Wanly tried to calm his mosque members' nerves.

Mr. Mohamud is scheduled to appear in federal court in Portland on Monday on a charge of attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction.

Many questions remain about the extent of Mr. Mohamud's connections to Islamic extremists, whom investigators say he wrote to and plotted with, as well as about the apparent contradictions in his personal life, as a studious, friendly teenager and a young man seeking to wage jihad within his adopted country.

"When you think of someone doing what he did, you think of some crazy kind of guy," said Mohamed Kassim, 21, a fellow Oregon State student who knew Mr. Mohamud from around campus. "He wasn't like that. He was just like everybody else."

Many Muslims in Oregon worried that they would face a backlash. And on Sunday, local Muslim leaders emphasized that the case was an isolated incident.

"If this kid's being radicalized, it's not from the locals," said Jesse Day, a spokesman for the Islamic Center of Portland and Masjed As-Saber, where Mr. Mohamud sometimes worshiped.

The president of the center, Imtiaz Khan, shared that concern, and said in an interview that he worried that the mosque and Islam in general would be portrayed unfairly because of the arrest. On Sunday morning, a Portland police car was parked outside the mosque.

"We have women and children here that we want to protect," Mr. Khan said.

But a sense of suspicion and worry prevailed.

Mr. Khan and Mr. Day said several people who worship at the mosque said that F.B.I. agents had knocked on their doors late at night on the day of Mr. Mohamud's arrest, but that none had agreed to speak to the agents.

"People were finding cards in the doors that said F.B.I.," Mr. Day said.

The mosque, the largest in Portland, has been at the center of controversy before. In 2002, the mosque's imam, Sheik Mohamed Abdirahman Kariye, also a naturalized American citizen from Somalia, was arrested at Portland International Airport.

Prosecutors said that trace elements of TNT were found in his luggage, though those tests were later said to be inconclusive and he was not convicted of any crime.

Mr. Kariye did not immediately respond to a request for comment made through Mr. Day, but Mr. Khan repeated that Mr. Mohamud's actions were his own.

"Whatever this event is, it has nothing to do with the mosque," Mr. Khan said.

Mr. Mohamud, his younger sister and their parents had long lived in the Portland area, including in Beaverton, a suburb that has a small Somali population.

Mr. Mohamud's family fled Somalia in the early 1990s, and his father, Osman Barre, a well-educated engineer, worked to establish them in Oregon.

Osman was very sophisticated," said Chris Oace, a former refugee worker for Ecumenical Ministries of Oregon who helped the family resettle here in the early 1990s. "Some refugees are afraid of having Christian churches help them. But it wasn't an issue with his family at all."

Stephanie Napier, a former neighbor, said that the family had been quiet but friendly and that Mr. Mohamud's mother was fiercely proud of her only son.

"He seemed like a great kid," she said. "His mother spoke very highly of him. He always did what he was told and got great grades."

At some point over the last year or so, however, Mr. Mohamud's parents separated, and tensions grew in the family.

A friend of the family said Mr. Barre, who eventually became an engineer for Intel, could be temperamental.

Several people who said they knew Mr. Mohamud's family said they believed that his parents had reported him to law enforcement authorities, citing concerns that his views were becoming extreme. Those people refused to be quoted by name.

A law enforcement official, who was not authorized to publicly discuss certain aspects of the case, said investigators first became aware of Mr. Mohamud because of what the official said were his efforts to connect with Islamic extremists through e-mail.

Soon after that they received information from Mr. Mohamud's father, alerting them to what the official described as increased radicalization. According to the federal affidavit for his arrest, Mr. Mohamud at one point wrote in an e-mail that he felt "betrayed" by his family.

Law enforcement officials also confirmed that his parents had marital problems, but said they were irrelevant to the investigation.

Family members could not be reached for comment.

Cawo Abdi, a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota who studies Somali youth, said some young Somali men in the United States struggle to find a sense of belonging.

"They are trying to find somewhere they can fit in," Ms. Abdi said. "This has led some to join gangs, while others are lured by the Jihadist Web sites and YouTube videos on the Internet."

But for those who knew Mr. Mohamud in Corvallis, a liberal college town whose engineering program draws a sizable number of international students, assimilation did not seem to be the problem.

Mr. Kassim, the Oregon State student, said that Mr. Mohamud seemed to be a normal student, playing basketball at the recreation center, talking about girls and obsessing about the Portland Trailblazers, his favorite team.

On Sunday, such trivial concerns had been replaced by more pressing issues.

Outside the Corvallis mosque, a steady stream of well-wishers -- both Muslim and non-Muslim -- arrived during the day. At the rear of the unmarked structure, a charred and broken window was boarded up. Mosque members said there had been extensive damage, including burned Korans, wedding and death certificates, and other items.

Mohamed Alyajouri, 31, who is married and has three children, said he was in shock when he heard of Mr. Mohamud's arrest and was concerned about the effect on Muslims everywhere.

"This kid had friends here, went to school here," Mr. Alyajouri said. "It's so stupid. Nobody I know thinks that way. But we have to deal with this now."

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world