Research participant David Myers in a head brace. The machine, he says, rocked him to sleep.

Washington:

In 1964, Gulak and the other test subjects for the research were sent out on a boat traveling through rough waters off the coast Nova Scotia.

The ship rolled and pitched in a storm, tilting back and forth. But those who'd volunteered for the research were immune to motion sickness.

"Honestly, it was a wonderful time," said Gulak who, along with the other research test subjects, is deaf.

It is, however, probably safe to assume that those who were conducting the research -- who were not immune to motion sickness -- did not share this view.

"We were enjoying ourselves," Gulak recalled. "We actually had meals during the storm. And when they saw us eating, it made them even more sick, and they were vomiting."

For years, Gulak and others took part in research conducted by the U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine, conducted during the early days of the American space program more than a half-century ago. By extension, these test subjects helped NASA, which sponsored the work, according to Bill Barry, NASA's chief historian. They spent days in rotating rooms. They went up on parabolic flights, floating in zero gravity. And they rocked on that boat out in the angry waters.

"They were interested in researching balance and motion sickness, sea sickness and the like. That kind of thing," said Harry Larson, 79, who took part in the research. "Because NASA wanted to know more about how man could perform in a zero-gravity environment."

The research and the stories of the participants are detailed in an on-campus exhibit at Gallaudet University, which opened in April.

"I'm a red-blooded American," Gulak said. "I wanted to serve our country the best that I could. Being that I'm deaf, I could not join the military. . . . It was my way of serving."

The research has deep ties with Gallaudet University, the nation's premier college for the deaf and hard of hearing. Many of those who participated were selected when officials came to the Washington, D.C., campus in search of test subjects.

"All of those experiments we went through, none of us got sick," said another participant, David Myers, 80. "There would be two groups, my group and the hearing group, and the hearing group, many of them would always get sick. And we never got sick. So that, essentially, was the whole purpose of research, was to find out ways to prevent motion sickness."

Here's the gist of how this all came to be: In 1961, a doctor named Ashton Graybiel and other personnel from the U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine visited Gallaudet, Jean Bergey, associate director of the Drs. John S. & Betty J. Schuchman Deaf Documentary Center, said in an email to The Washington Post.

Officials tested more than 100 students, faculty and staff, narrowing the group to a handful, mostly students. The research with that group continued for years.

"All but one of the selected test subjects became deaf from spinal meningitis, which impacted their inner ear physiology," Bergey wrote in an online post on the National Air and Space Museum website. "This meant they could endure motion and gravitational forces that make most people nauseous.

"The ability to withstand intense movement turned the so-called 'labyrinthine defect' into a valuable research asset -- no matter the test of equilibrium, the deaf participants simply never got sick," Bergey wrote. The test subjects were selected for "weightlessness, balance, and motion sickness experiments."

"Harry Larson, one of the research participants, explained, 'We were different in a way they needed,'" Bergey wrote. "Indeed, their difference made it possible for researchers to explore human reactions to weightless environments and extreme motion and to better understand the complexity of entangled human sensory systems."

Bergey said in an email that she knew of no other research projects that involved Gallaudet and the U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine or NASA.

Hearing loss wasn't really a factor in the research, said Myers, one of the participants. Instead, those who were involved didn't have a functioning vestibular system, which meant their balance and sense of movement were affected and they didn't get motion-sick.

Myers also explained in an email that this happened at a time when "interpreter services was neither a right nor expected by our group."

"About the only interpreting made available was by hearing family members who by growing up in a deaf family learned sign language and could serve as interpreter for a deaf family member," he wrote. "Some churches would ask family members to interpret church services for their deaf members. Interpreting as an occupation was unheard of as interpreter jobs did not exist."

The group for Gallaudet participated in the research with "limited preparation and understanding of the tasks at hand," Myers wrote.

"Brief written instructions were often provided which focused mostly on what we were supposed to do rather than providing an understanding of the nature of the tasks," he wrote. "This lack of interpreter services was a reflection of the times rather than any denial of that need for the services."  (Some interviews for this story, including in-person conversations with Myers, Larson and Gulak, were done with through interpreters.)

(Some interviews for this story, including in-person conversations with Myers, Larson and Gulak, were done with through interpreters.)

Larson remembers when the Navy came to the Gallaudet campus, looking for volunteers to be part of a space research program. At the time, he was a senior at the university; it was the spring of 1961. Larson volunteered, he said, "just for fun."

"Overall, I have to say, I was really pleased to be able to go on the different trips," he said. "It was an adventure to us. We certainly weren't thinking about any of the danger. It was more of like, fun things to do."

Larson was also on the ship that was tossed in waters off Nova Scotia and remembers traveling to Ohio for zero-gravity flights. He recalled one project in which he had to stand up against a post. He was strapped to the post with Velcro, the first time he'd seen the material. Larson said he spent hours like that, while others took pictures of his eyes.

"That was really tough," he said, "just having to stand for that long."

Myers recalled a rotating room where those involved in the research would stay, even to eat and sleep, for days. Initially, he said, it was tough to walk, but by the second or third day, the research subjects started to adapt.

"It was a lot of work. A lot of hard work," he said. "For the [hearing participants], many of them got extremely ill in that room."

Myers said he once met John Glenn, a Marine Corps fighter pilot and the first American to orbit Earth. Glenn told Myers that he had heard about the Gallaudet subjects.

"Once he got word that there was a group of deaf folks who would never get sick," Myers said, "he quote 'envied' us."

Research on this kind of information can be found at the Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Laboratory at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. Paul DiZio, an associate professor at Brandeis and associate director of the lab who attended the opening of the Gallaudet exhibit, told the crowd that the work of these research subjects comes up quite frequently, even decades later.

"The conversation gets difficult, and we forget where we are, and we say to ourselves, well, what do we know?" he said. "What it comes down to is what we learned from these people."

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

The ship rolled and pitched in a storm, tilting back and forth. But those who'd volunteered for the research were immune to motion sickness.

"Honestly, it was a wonderful time," said Gulak who, along with the other research test subjects, is deaf.

It is, however, probably safe to assume that those who were conducting the research -- who were not immune to motion sickness -- did not share this view.

"We were enjoying ourselves," Gulak recalled. "We actually had meals during the storm. And when they saw us eating, it made them even more sick, and they were vomiting."

For years, Gulak and others took part in research conducted by the U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine, conducted during the early days of the American space program more than a half-century ago. By extension, these test subjects helped NASA, which sponsored the work, according to Bill Barry, NASA's chief historian. They spent days in rotating rooms. They went up on parabolic flights, floating in zero gravity. And they rocked on that boat out in the angry waters.

"They were interested in researching balance and motion sickness, sea sickness and the like. That kind of thing," said Harry Larson, 79, who took part in the research. "Because NASA wanted to know more about how man could perform in a zero-gravity environment."

The research and the stories of the participants are detailed in an on-campus exhibit at Gallaudet University, which opened in April.

"I'm a red-blooded American," Gulak said. "I wanted to serve our country the best that I could. Being that I'm deaf, I could not join the military. . . . It was my way of serving."

The research has deep ties with Gallaudet University, the nation's premier college for the deaf and hard of hearing. Many of those who participated were selected when officials came to the Washington, D.C., campus in search of test subjects.

"All of those experiments we went through, none of us got sick," said another participant, David Myers, 80. "There would be two groups, my group and the hearing group, and the hearing group, many of them would always get sick. And we never got sick. So that, essentially, was the whole purpose of research, was to find out ways to prevent motion sickness."

Here's the gist of how this all came to be: In 1961, a doctor named Ashton Graybiel and other personnel from the U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine visited Gallaudet, Jean Bergey, associate director of the Drs. John S. & Betty J. Schuchman Deaf Documentary Center, said in an email to The Washington Post.

Officials tested more than 100 students, faculty and staff, narrowing the group to a handful, mostly students. The research with that group continued for years.

"All but one of the selected test subjects became deaf from spinal meningitis, which impacted their inner ear physiology," Bergey wrote in an online post on the National Air and Space Museum website. "This meant they could endure motion and gravitational forces that make most people nauseous.

"The ability to withstand intense movement turned the so-called 'labyrinthine defect' into a valuable research asset -- no matter the test of equilibrium, the deaf participants simply never got sick," Bergey wrote. The test subjects were selected for "weightlessness, balance, and motion sickness experiments."

"Harry Larson, one of the research participants, explained, 'We were different in a way they needed,'" Bergey wrote. "Indeed, their difference made it possible for researchers to explore human reactions to weightless environments and extreme motion and to better understand the complexity of entangled human sensory systems."

Bergey said in an email that she knew of no other research projects that involved Gallaudet and the U.S. Naval School of Aviation Medicine or NASA.

Hearing loss wasn't really a factor in the research, said Myers, one of the participants. Instead, those who were involved didn't have a functioning vestibular system, which meant their balance and sense of movement were affected and they didn't get motion-sick.

Myers also explained in an email that this happened at a time when "interpreter services was neither a right nor expected by our group."

"About the only interpreting made available was by hearing family members who by growing up in a deaf family learned sign language and could serve as interpreter for a deaf family member," he wrote. "Some churches would ask family members to interpret church services for their deaf members. Interpreting as an occupation was unheard of as interpreter jobs did not exist."

The group for Gallaudet participated in the research with "limited preparation and understanding of the tasks at hand," Myers wrote.

"Brief written instructions were often provided which focused mostly on what we were supposed to do rather than providing an understanding of the nature of the tasks," he wrote. "This lack of interpreter services was a reflection of the times rather than any denial of that need for the services."

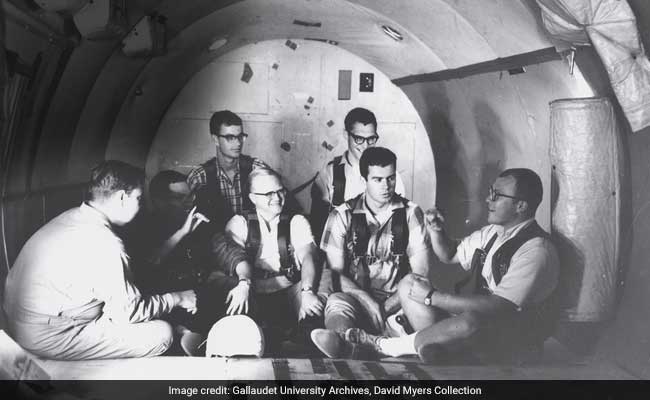

Deaf test subjects prepare for zero-gravity flight.

Larson remembers when the Navy came to the Gallaudet campus, looking for volunteers to be part of a space research program. At the time, he was a senior at the university; it was the spring of 1961. Larson volunteered, he said, "just for fun."

"Overall, I have to say, I was really pleased to be able to go on the different trips," he said. "It was an adventure to us. We certainly weren't thinking about any of the danger. It was more of like, fun things to do."

Larson was also on the ship that was tossed in waters off Nova Scotia and remembers traveling to Ohio for zero-gravity flights. He recalled one project in which he had to stand up against a post. He was strapped to the post with Velcro, the first time he'd seen the material. Larson said he spent hours like that, while others took pictures of his eyes.

"That was really tough," he said, "just having to stand for that long."

Myers recalled a rotating room where those involved in the research would stay, even to eat and sleep, for days. Initially, he said, it was tough to walk, but by the second or third day, the research subjects started to adapt.

"It was a lot of work. A lot of hard work," he said. "For the [hearing participants], many of them got extremely ill in that room."

Myers said he once met John Glenn, a Marine Corps fighter pilot and the first American to orbit Earth. Glenn told Myers that he had heard about the Gallaudet subjects.

"Once he got word that there was a group of deaf folks who would never get sick," Myers said, "he quote 'envied' us."

Research on this kind of information can be found at the Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Laboratory at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. Paul DiZio, an associate professor at Brandeis and associate director of the lab who attended the opening of the Gallaudet exhibit, told the crowd that the work of these research subjects comes up quite frequently, even decades later.

"The conversation gets difficult, and we forget where we are, and we say to ourselves, well, what do we know?" he said. "What it comes down to is what we learned from these people."

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world