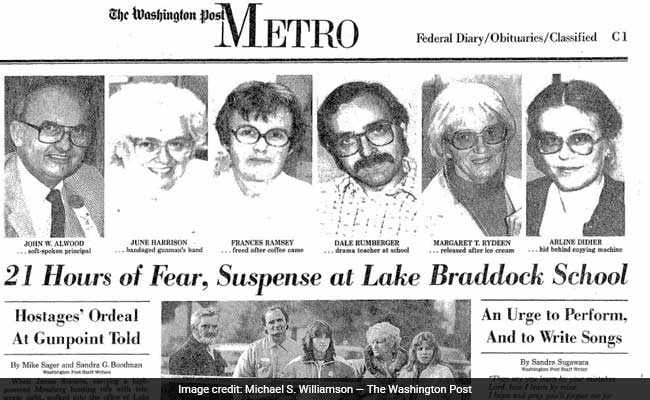

A story about the school attack on the front page of The Washington Post's Metro section.

New York:

Thirty-six years after he held 10 people hostage for 21 hours at a Virginia high school, onetime school shooter James Quentin Stevens is sitting at a restaurant in Winchester, Virginia. He orders a Mandarin salad, says grace when it arrives, then doesn't eat.

Stevens, 53, has a lot to say - too much to think about food. Decades ago, he walked into a school with a high-powered Mossberg hunting rifle, but took no lives, did his time and lived to tell the tale. Now, he said he wants to help young men like alleged Parkland shooter Nikolas Cruz - young men like the young man he once was - who have plotted attacks across the country.

His weapon is his life story.  When Stevens walked into Fairfax County's Lake Braddock Secondary School the afternoon of Nov. 10, 1982, he wasn't taken seriously. Not at first.

When Stevens walked into Fairfax County's Lake Braddock Secondary School the afternoon of Nov. 10, 1982, he wasn't taken seriously. Not at first.

"My first reaction was, 'Oh, they're promoting the play 'Oklahoma,' " Frances Churchman, who was taken hostage, said at the time. "We'd seen it the night before at the school."

But Stevens proved he was serious, firing a shot into the ceiling and taking nine hostages. A tenth hid behind a copy machine for 21 hours.

The 4,300-student school was evacuated. Police established a telephone line for negotiations and brought in Stevens' ex-girlfriend, who had just broken up with him, to talk him down.  The former girlfriend, Becca Schult, now a 53-year-old nurse living in California, described Stevens as an introvert, a quiet guitar player, the kind of guy who "always got a door for a woman."

The former girlfriend, Becca Schult, now a 53-year-old nurse living in California, described Stevens as an introvert, a quiet guitar player, the kind of guy who "always got a door for a woman."

"He didn't go in with the intent of hurting anybody," she said. "He went in with the intent of trying to reach me to talk to me."

Though media reports picked up on the jilted lover angle - one headline read "Lovelorn teen surrenders to police" - Stevens doesn't talk much about the relationship now, other than to acknowledge he was too young to handle it. He sees his attack less as the result of a relationship gone sour and more as a "road to Damascus moment" - a religious battle between good and evil that good won.

Stevens resisted taking calls for years - calls from reporters, radio stations, TV stations - asking him to explain the mind of mass school shooters.

Now, he imagines dying, going to heaven - he is going to go to heaven, he hopes - and Jesus asking: "Did you just keep your story, your precious jewel, to yourself?"

He was without a father figure after his biological dad left the family when he was 3. His mother remarried, but his stepfather was distant, and the couple divorced when Stevens was in his teens.

Remembering the attack, Stevens described what he called "demonic possession" - "voices" telling him to kill the hostages, to kill himself. He said he had "crazy eyes," briefly losing his peripheral vision. He described putting the gun - a present for his 16th birthday - in his mouth, then taking it out to scream "Get out!" at the hostages in a voice two or three octaves lower than his own, like Linda Blair in "The Exorcist."

An "out-of-body moment" followed, he said, as a hand clothed in a white robe reached out to him. He reached back and took it.

And he was saved.

"Peace came that I'd been looking for all my life," he said. Referencing a higher power, he continued: "All I did was touch this hand."

Over the next seven hours, Stevens said, he released a hostage every hour. A 1982 Post story said he traded one for four cups of coffee, another for a gallon of vanilla ice cream, and yet another for a large pizza with everything except anchovies.

At 10 a.m., Stevens kicked his rifle to a hostage negotiator. The siege was over.

Stevens hadn't killed anyone. He was sentenced to 4 1/2 years in prison and three years of community service. He paid the school $403 in damages.

"I want to prove to society and the judge the sentence he made is justified and prove to him that I'm not a criminal," he said after his sentencing.

He soon had a chance. Two-and-a-half-years into his sentence, he was sitting in a maximum-security prison when he learned he was part of an early-release program for young offenders. He got a job he held for five years teaching guitar to children with mental disabilities.

He got involved with Bible study and a Christian youth group. He got married and had a child - the first of his two children, both of whom he talks to regularly - but something wasn't right.

"I was always hiding my face," he said. "I was ashamed. I deserve to be in a prison. . . . I was just kind of keeping in my shell."

He performed in an Easter pageant in Washington, New York and Boston from 1985 until 1989, transforming into Christ, adorned with a crown of thorns and a loincloth to drag a wooden cross to the top of the Capitol steps.

After his time performing, he drifted to Nashville. Background checks made jobs difficult to find, so he often worked construction, including as a plumber at former Vice President Al Gore's Tennessee estate. After seeking out "every certification he could find," he said, he landed a tech job around 1999.

He had a career in computers and a new name - "TJ Stevens," a stage name he began using in everyday life - but his story of redemption was idle.  "I was serving myself," Stevens said.

"I was serving myself," Stevens said.

Then on Nov. 15, 2003, two Black Hawk helicopters crashed in Mosul, Iraq, killing 17 soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division. Stevens heard about the crash on the radio.

"I was so angry," Stevens said. "I felt the hurt."

That night, he wrote "The Unknown Soldier," a ballad that paid tribute to the women and children that soldiers in uniform leave behind when they go to battle.

The song was spun on Nashville radio stations. Stevens was invited to perform at Fort Campbell in Kentucky, home of the 101st Airborne, where he said he met then-Brigadier Gen. David Petraeus.

"God, this has to be you," Stevens said he thought at the time. "Now you have a general hiring me." (A Fort Campbell spokesman couldn't confirm the story. A Petraeus spokeswoman said "it's possible but the general does not have a clear recollection.")

He pressed about 1,000 copies of the song on CD and distributed them with envelopes inside, soliciting donations for soldiers and their families with the help of a charity.

"The Unknown Soldier" was "a fluke," he said, and he was a one-hit wonder.

"Nashville can embrace you or chew you up and spit you out," he said. "It's more political than the United States congress."

Meanwhile, his second marriage fell apart. He moved back to Winchester in 2006, he said, in "depressed mode," living on his aging father's property. When a local pastor invited Stevens to sing at church, he wasn't sure he should.

Then he did. Just one song.

"That's all it took," Stevens said. "He got me back in church. I recommitted my life to Christ. Again."

Armed with Nashville know-how, he started booking Christian bands in Winchester. Some concerts' proceeds went to charitable causes - to pay the medical bills of a young girl with cancer or pay part of a hospital bill for Jacob Aiden Hess, a 12-year-old Virginia boy who died in 2016 after playing "the choking game."

Reluctantly, the school shooter once known as James Quentin Stevens began to tell his own story. The first time was in 2015 at What's New Worship, a Winchester church located in a TraveLodge banquet room.

Pastor Andy Combs said Stevens was hesitant at first.

"I don't know what TJ is going to tell you he was then," Combs recalled warning the congregation, "but he is a different person now."

As Stevens began to talk, people cried. And people Googled. Was the church's quiet audio/visual guy really a school shooter?

After the Parkland shooting he made a commitment to do even more. He wants to reach out to troubled teens with violent thoughts.

"I would gladly sit down and talk to any child there is who is thinking about doing something like this," he said.

Last year, he shared his story at another Winchester church with a woman who'd lived through the ordeal.

Bethany Searfoss, now 50, was 14 when she was evacuated from Lake Braddock on the day Stevens took the hostages. She recalled "mass chaos," she said - police, firetrucks and being escorted in her gym clothes by a SWAT team. Then, one day in church at What's New Worship center, the villain of the tale was unexpectedly telling it to her. She's still the only victim of Stevens's siege with whom he has discussed the ordeal.

She was moved. She went up to him after the service and "lost it," she said. He asked for her forgiveness, and she didn't hesitate to give it.

"I have to forgive him because God forgave me," she said.

Stevens said God has forgiven him. The state of Virginia also pardoned him in 2016, restoring his right to vote, but not his right to own a gun.

Though he thinks armed veterans could help prevent school shootings, he's not much of a gun guy himself anyway. Not after Lake Braddock.

"I don't like having them in the house," he said.

Stevens said he's spent decades thinking about the pain he caused his victims. He said he hopes they know their pain "does not go unnoticed by God."

The great thing about his story is that he can always tell it again.

"It's the beginning," he said. "Just when you think God is done with us, it's the beginning."

The Washington Post's Magda Jean-Louis and Eddy Palanzo contributed to this report.

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Stevens, 53, has a lot to say - too much to think about food. Decades ago, he walked into a school with a high-powered Mossberg hunting rifle, but took no lives, did his time and lived to tell the tale. Now, he said he wants to help young men like alleged Parkland shooter Nikolas Cruz - young men like the young man he once was - who have plotted attacks across the country.

His weapon is his life story.

Stevens now wants to help young people like Nikolas Cruz, the Parkland school shooting accused.

"My first reaction was, 'Oh, they're promoting the play 'Oklahoma,' " Frances Churchman, who was taken hostage, said at the time. "We'd seen it the night before at the school."

But Stevens proved he was serious, firing a shot into the ceiling and taking nine hostages. A tenth hid behind a copy machine for 21 hours.

The 4,300-student school was evacuated. Police established a telephone line for negotiations and brought in Stevens' ex-girlfriend, who had just broken up with him, to talk him down.

Stevens was reunited with Bethany Searfoss, one of the students evacuated from the school.

"He didn't go in with the intent of hurting anybody," she said. "He went in with the intent of trying to reach me to talk to me."

Though media reports picked up on the jilted lover angle - one headline read "Lovelorn teen surrenders to police" - Stevens doesn't talk much about the relationship now, other than to acknowledge he was too young to handle it. He sees his attack less as the result of a relationship gone sour and more as a "road to Damascus moment" - a religious battle between good and evil that good won.

Stevens resisted taking calls for years - calls from reporters, radio stations, TV stations - asking him to explain the mind of mass school shooters.

Now, he imagines dying, going to heaven - he is going to go to heaven, he hopes - and Jesus asking: "Did you just keep your story, your precious jewel, to yourself?"

He was without a father figure after his biological dad left the family when he was 3. His mother remarried, but his stepfather was distant, and the couple divorced when Stevens was in his teens.

Remembering the attack, Stevens described what he called "demonic possession" - "voices" telling him to kill the hostages, to kill himself. He said he had "crazy eyes," briefly losing his peripheral vision. He described putting the gun - a present for his 16th birthday - in his mouth, then taking it out to scream "Get out!" at the hostages in a voice two or three octaves lower than his own, like Linda Blair in "The Exorcist."

An "out-of-body moment" followed, he said, as a hand clothed in a white robe reached out to him. He reached back and took it.

And he was saved.

"Peace came that I'd been looking for all my life," he said. Referencing a higher power, he continued: "All I did was touch this hand."

Over the next seven hours, Stevens said, he released a hostage every hour. A 1982 Post story said he traded one for four cups of coffee, another for a gallon of vanilla ice cream, and yet another for a large pizza with everything except anchovies.

At 10 a.m., Stevens kicked his rifle to a hostage negotiator. The siege was over.

Stevens hadn't killed anyone. He was sentenced to 4 1/2 years in prison and three years of community service. He paid the school $403 in damages.

"I want to prove to society and the judge the sentence he made is justified and prove to him that I'm not a criminal," he said after his sentencing.

He soon had a chance. Two-and-a-half-years into his sentence, he was sitting in a maximum-security prison when he learned he was part of an early-release program for young offenders. He got a job he held for five years teaching guitar to children with mental disabilities.

He got involved with Bible study and a Christian youth group. He got married and had a child - the first of his two children, both of whom he talks to regularly - but something wasn't right.

"I was always hiding my face," he said. "I was ashamed. I deserve to be in a prison. . . . I was just kind of keeping in my shell."

He performed in an Easter pageant in Washington, New York and Boston from 1985 until 1989, transforming into Christ, adorned with a crown of thorns and a loincloth to drag a wooden cross to the top of the Capitol steps.

After his time performing, he drifted to Nashville. Background checks made jobs difficult to find, so he often worked construction, including as a plumber at former Vice President Al Gore's Tennessee estate. After seeking out "every certification he could find," he said, he landed a tech job around 1999.

He had a career in computers and a new name - "TJ Stevens," a stage name he began using in everyday life - but his story of redemption was idle.

At the What's New Worship center, Stevens volunteers as a sound man and musician.

Then on Nov. 15, 2003, two Black Hawk helicopters crashed in Mosul, Iraq, killing 17 soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division. Stevens heard about the crash on the radio.

"I was so angry," Stevens said. "I felt the hurt."

That night, he wrote "The Unknown Soldier," a ballad that paid tribute to the women and children that soldiers in uniform leave behind when they go to battle.

The song was spun on Nashville radio stations. Stevens was invited to perform at Fort Campbell in Kentucky, home of the 101st Airborne, where he said he met then-Brigadier Gen. David Petraeus.

"God, this has to be you," Stevens said he thought at the time. "Now you have a general hiring me." (A Fort Campbell spokesman couldn't confirm the story. A Petraeus spokeswoman said "it's possible but the general does not have a clear recollection.")

He pressed about 1,000 copies of the song on CD and distributed them with envelopes inside, soliciting donations for soldiers and their families with the help of a charity.

"The Unknown Soldier" was "a fluke," he said, and he was a one-hit wonder.

"Nashville can embrace you or chew you up and spit you out," he said. "It's more political than the United States congress."

Meanwhile, his second marriage fell apart. He moved back to Winchester in 2006, he said, in "depressed mode," living on his aging father's property. When a local pastor invited Stevens to sing at church, he wasn't sure he should.

Then he did. Just one song.

"That's all it took," Stevens said. "He got me back in church. I recommitted my life to Christ. Again."

Armed with Nashville know-how, he started booking Christian bands in Winchester. Some concerts' proceeds went to charitable causes - to pay the medical bills of a young girl with cancer or pay part of a hospital bill for Jacob Aiden Hess, a 12-year-old Virginia boy who died in 2016 after playing "the choking game."

Reluctantly, the school shooter once known as James Quentin Stevens began to tell his own story. The first time was in 2015 at What's New Worship, a Winchester church located in a TraveLodge banquet room.

Pastor Andy Combs said Stevens was hesitant at first.

"I don't know what TJ is going to tell you he was then," Combs recalled warning the congregation, "but he is a different person now."

As Stevens began to talk, people cried. And people Googled. Was the church's quiet audio/visual guy really a school shooter?

After the Parkland shooting he made a commitment to do even more. He wants to reach out to troubled teens with violent thoughts.

"I would gladly sit down and talk to any child there is who is thinking about doing something like this," he said.

Last year, he shared his story at another Winchester church with a woman who'd lived through the ordeal.

Bethany Searfoss, now 50, was 14 when she was evacuated from Lake Braddock on the day Stevens took the hostages. She recalled "mass chaos," she said - police, firetrucks and being escorted in her gym clothes by a SWAT team. Then, one day in church at What's New Worship center, the villain of the tale was unexpectedly telling it to her. She's still the only victim of Stevens's siege with whom he has discussed the ordeal.

She was moved. She went up to him after the service and "lost it," she said. He asked for her forgiveness, and she didn't hesitate to give it.

"I have to forgive him because God forgave me," she said.

Stevens said God has forgiven him. The state of Virginia also pardoned him in 2016, restoring his right to vote, but not his right to own a gun.

Though he thinks armed veterans could help prevent school shootings, he's not much of a gun guy himself anyway. Not after Lake Braddock.

"I don't like having them in the house," he said.

Stevens said he's spent decades thinking about the pain he caused his victims. He said he hopes they know their pain "does not go unnoticed by God."

The great thing about his story is that he can always tell it again.

"It's the beginning," he said. "Just when you think God is done with us, it's the beginning."

The Washington Post's Magda Jean-Louis and Eddy Palanzo contributed to this report.

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world