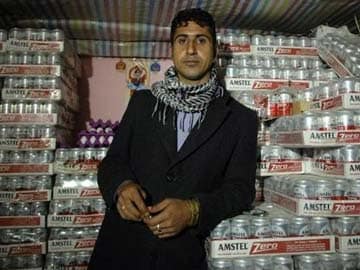

A smuggler poses with cartons of beer during an alcohol smuggling operation to Iran at the border near Sulaimaniya, 260 km (162 miles) northeast of Baghdad on March 20, 2010

Ankara:

"Have a shot of tequila first, cheer up!" Shahriyar tells guests gathered at his luxury apartment in Tehran.

His girlfriend, Shima, said they party every weekend.

"Shahriyar has one rule: bring your booze! We drink until morning," she told Reuters on a FaceTime call, as lights flashed to rap music in the background.

Despite the ban on alcohol and frequent police raids, drinking in Iran is widespread, especially among the wealthy. Because the Shiite-dominated Muslim state has no discotheques or nightclubs, it all takes place at home, behind closed doors.

Some of the alcohol is smuggled in, but many resourceful Iranians make their own.

"My friends and I routinely gather to stamp down on grapes in my bathtub," said Hesam, a 28-year-old music teacher in Tehran, asking to be identified only by his first name. "It's fun, a cleansing ritual almost."

Some take considerable pride in their results, to the delight of their acquaintances.

"I have a friend who makes wine for his own consumption but gives me around 30 bottles per year as well," said 36-year-old Mousa, speaking from in the central city of Isfahan.

Only members of religious minorities - Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians - are allowed to brew, distill, ferment - and drink - discreetly in the privacy of their homes, and trade in liquor is forbidden. Catholic priests make their own wine for mass.

Yet wine-making has a long history in Iran. Scientists believe Stone Age settlers in what is now Iran drank wine with their olives and bread as early as 5,000 BC.

The renowned Shiraz variety of grape, named after the city in the south of the country, is said to have been brought back to Europe by the Crusaders.

Persian poets Hafez and Omar Khayyam extolled the virtues of the grape.

"What drunkenness is this that brings me hope? Who was the cup-bearer and whence the wine?" Hafez wrote in the 14th century.

In modern Iran, the Armenian community is the main source of home-brewed spirits, notably arak, a generic variety of vodka extracted from sun-dried grapes.

Amin, a 35-year-old sports trainer, has turned his 50-sq-meter yard into a vineyard and rigged up a crude apparatus in his dingy basement to make the spirit, which costs as little as 50 cents a litre.

Which all means if you aren't inclined to make your own, wine, beer and moonshine are just a phone call away.

"You don't even need to leave the house," said Reza, a computer engineer in Tehran. "Nasser, the Brewer, will deliver it at your door, VIP service."

WESTERN PLOT

The availability of alcohol has caused alarm among the country's clerical leaders, many of whom accuse the West of plotting to lure Iranians away from pious religious observance.

The number of police raids has declined since the pragmatic President Hassan Rouhani took office in August, but the ban on alcohol and severe punishments for producing and consuming it remain intact, for health as well as religious reasons.

And in fact alcohol abuse and alcohol poisoning are becoming real problems.

There are as many as 200,000 alcoholics in Iran, according to Iranian media reports, and some believe the number is higher. Last September, a permit was quietly issued for the country's first alcohol rehabilitation centre in Tehran.

"The centre was set up in Tehran to help our citizens. You cannot resolve the problem by ignoring it," a health ministry official told Reuters, but would not give any details about the number of people under treatment or even the centre's location.

Home-brewed drinks can cause blindness and even death. Iranian media often carry reports of deaths caused by alcohol, or "mashroob".

Last year Iranian health officials warned the government over the increasing number of "victims of home-made alcohol", calling on the government to take action.

Industrial alcohol is available in supermarkets, purportedly for use in manufacturing but widely consumed.

"Ettehadiye Industrial alcohol (at 140 proof) is available in supermarkets for only 80,000 Iranian rials with orange, pineapple and apple flavours," said Hojjat, 25, a student in Tehran.

The other big business around alcohol is smuggling. The Iranian judiciary has accused border officials of complicity in the contraband trade.

The elite Revolutionary Guards formed in the wake of the 1979 Islamic revolution, who are in charge of controlling the borders, are widely believed to have a monopoly on the activity, securing a profit of around $12 billion annually, according to opposition websites.

"The Guards is like an investment company with a complex of business empires and trading companies ... They are involved," said Mohsen Sazegara, a former deputy prime minister of Iran and founder of the Guard Corps who is now an activist based in the United States.

The corps declined to comment on the accusation.

Brand names smuggled in from neighbouring Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan sell for as much as $70 a bottle. A can of beer is just under $8 a can and bottles of tequila and French brandy are easy to find on the black market for $100.

Russian and Georgian vodka finds its way into the Islamic Republic through the rugged Caucasus, across Central Asia's deserts and the Caspian Sea.

Police seizures cause temporary price hikes on the street, but prices and supplies soon recover.

Back in Tehran, at the apartment owned by his wealthy businessman father, Shahriyar says his alcohol-fuelled parties allow his circle to get around the social restrictions imposed by the Islamic establishment.

"By drinking we forget about our problems," he said. "Otherwise we will go crazy with all the limitations on young people in Iran."

His girlfriend, Shima, said they party every weekend.

"Shahriyar has one rule: bring your booze! We drink until morning," she told Reuters on a FaceTime call, as lights flashed to rap music in the background.

Despite the ban on alcohol and frequent police raids, drinking in Iran is widespread, especially among the wealthy. Because the Shiite-dominated Muslim state has no discotheques or nightclubs, it all takes place at home, behind closed doors.

Some of the alcohol is smuggled in, but many resourceful Iranians make their own.

"My friends and I routinely gather to stamp down on grapes in my bathtub," said Hesam, a 28-year-old music teacher in Tehran, asking to be identified only by his first name. "It's fun, a cleansing ritual almost."

Some take considerable pride in their results, to the delight of their acquaintances.

"I have a friend who makes wine for his own consumption but gives me around 30 bottles per year as well," said 36-year-old Mousa, speaking from in the central city of Isfahan.

Only members of religious minorities - Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians - are allowed to brew, distill, ferment - and drink - discreetly in the privacy of their homes, and trade in liquor is forbidden. Catholic priests make their own wine for mass.

Yet wine-making has a long history in Iran. Scientists believe Stone Age settlers in what is now Iran drank wine with their olives and bread as early as 5,000 BC.

The renowned Shiraz variety of grape, named after the city in the south of the country, is said to have been brought back to Europe by the Crusaders.

Persian poets Hafez and Omar Khayyam extolled the virtues of the grape.

"What drunkenness is this that brings me hope? Who was the cup-bearer and whence the wine?" Hafez wrote in the 14th century.

In modern Iran, the Armenian community is the main source of home-brewed spirits, notably arak, a generic variety of vodka extracted from sun-dried grapes.

Amin, a 35-year-old sports trainer, has turned his 50-sq-meter yard into a vineyard and rigged up a crude apparatus in his dingy basement to make the spirit, which costs as little as 50 cents a litre.

Which all means if you aren't inclined to make your own, wine, beer and moonshine are just a phone call away.

"You don't even need to leave the house," said Reza, a computer engineer in Tehran. "Nasser, the Brewer, will deliver it at your door, VIP service."

WESTERN PLOT

The availability of alcohol has caused alarm among the country's clerical leaders, many of whom accuse the West of plotting to lure Iranians away from pious religious observance.

The number of police raids has declined since the pragmatic President Hassan Rouhani took office in August, but the ban on alcohol and severe punishments for producing and consuming it remain intact, for health as well as religious reasons.

And in fact alcohol abuse and alcohol poisoning are becoming real problems.

There are as many as 200,000 alcoholics in Iran, according to Iranian media reports, and some believe the number is higher. Last September, a permit was quietly issued for the country's first alcohol rehabilitation centre in Tehran.

"The centre was set up in Tehran to help our citizens. You cannot resolve the problem by ignoring it," a health ministry official told Reuters, but would not give any details about the number of people under treatment or even the centre's location.

Home-brewed drinks can cause blindness and even death. Iranian media often carry reports of deaths caused by alcohol, or "mashroob".

Last year Iranian health officials warned the government over the increasing number of "victims of home-made alcohol", calling on the government to take action.

Industrial alcohol is available in supermarkets, purportedly for use in manufacturing but widely consumed.

"Ettehadiye Industrial alcohol (at 140 proof) is available in supermarkets for only 80,000 Iranian rials with orange, pineapple and apple flavours," said Hojjat, 25, a student in Tehran.

The other big business around alcohol is smuggling. The Iranian judiciary has accused border officials of complicity in the contraband trade.

The elite Revolutionary Guards formed in the wake of the 1979 Islamic revolution, who are in charge of controlling the borders, are widely believed to have a monopoly on the activity, securing a profit of around $12 billion annually, according to opposition websites.

"The Guards is like an investment company with a complex of business empires and trading companies ... They are involved," said Mohsen Sazegara, a former deputy prime minister of Iran and founder of the Guard Corps who is now an activist based in the United States.

The corps declined to comment on the accusation.

Brand names smuggled in from neighbouring Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan sell for as much as $70 a bottle. A can of beer is just under $8 a can and bottles of tequila and French brandy are easy to find on the black market for $100.

Russian and Georgian vodka finds its way into the Islamic Republic through the rugged Caucasus, across Central Asia's deserts and the Caspian Sea.

Police seizures cause temporary price hikes on the street, but prices and supplies soon recover.

Back in Tehran, at the apartment owned by his wealthy businessman father, Shahriyar says his alcohol-fuelled parties allow his circle to get around the social restrictions imposed by the Islamic establishment.

"By drinking we forget about our problems," he said. "Otherwise we will go crazy with all the limitations on young people in Iran."

© Thomson Reuters 2014