Fighting under his given name of Cassius Clay, Muhammad Ali won a gold medal in the light heavyweight competition at the 1960 Olympics in Rome.

Former heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali, the most important, complex and polarizing athlete of our time, died Friday night at an Arizona hospital. He was 74. He had suffered for decades from Parkinson's disease, a progressive neurological disorder, and was being treated in the hospital in recent days for a respiratory issue.

"After a 32-year battle with Parkinson's disease, Muhammad Ali has passed away. . . . The three-time World Heavyweight Champion boxer died this evening," Bob Gunnell, a family spokesman, told NBC News.

Ali may not have been the world's greatest athlete, or even the best boxer of all time - though he is certainly in both discussions. What is indisputable, though, is he was the most beautiful athlete we had ever seen, and likely ever will again - beautiful not so much in the common sense of physical attraction, but in the classical sense, the platonic sense.

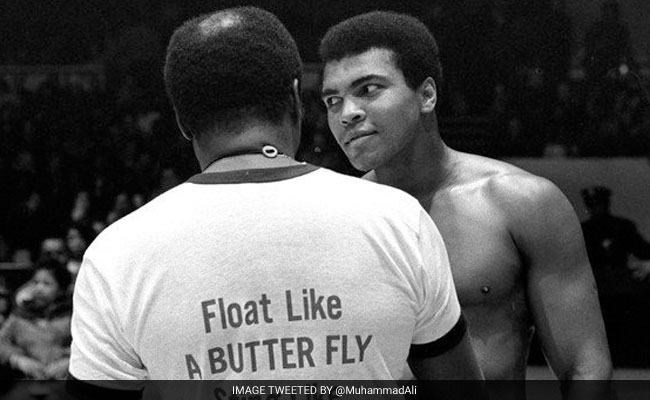

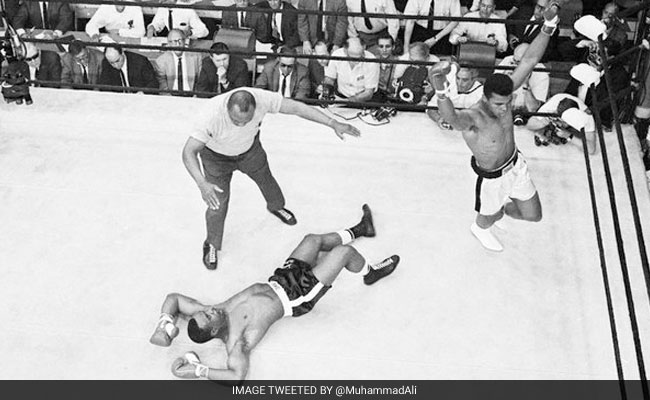

He was beautiful in motion, the way he danced in the ring - the patented Ali Shuffle - as he circled another victim. And he was beautiful in complete stillness, as in the many iconic photographs of him: standing over Sonny Liston in 1965, his arm cocked in rage; leaning on the rope, glistening with sweat, during a break from training; delivering a devastating right hook to Joe Frazier; clowning with the Beatles; mugging for the camera.

He was beautiful in motion, the way he danced in the ring - the patented Ali Shuffle - as he circled another victim. And he was beautiful in complete stillness, as in the many iconic photographs of him: standing over Sonny Liston in 1965, his arm cocked in rage; leaning on the rope, glistening with sweat, during a break from training; delivering a devastating right hook to Joe Frazier; clowning with the Beatles; mugging for the camera.

The camera loved him almost as much as people did.

Ali was beautiful when he smiled, which was often, and beautiful in anger - real or mock. He was beautiful in his youth - as Cassius Clay, son of Louisville, a teenaged Olympic champion, before the decision to turn pro, the conversion to Islam and the change of name - and he was beautiful as an old man, shadow-boxing for the cameras the way old ex-champs are supposed to do, or doing magic tricks for the kids.

Ali was beautiful even as Parkinson's disease slowly but steadily robbed him of the things we thought had made him so beautiful - his rippled muscles, his silly facial expressions, his mastery of language, his voice. It was enough just to look at him and remember what he was when he was younger. He was beautiful when he famously appeared, dressed in white, to light the Olympic flame signaling the start of the 1996 Atlanta Summer Games, his right hand gripping the torch, his left hand gripped by tremors. His refusal to hide his disease away from the public was, in its own way, an exceedingly beautiful thing.

Ali was beautiful even as Parkinson's disease slowly but steadily robbed him of the things we thought had made him so beautiful - his rippled muscles, his silly facial expressions, his mastery of language, his voice. It was enough just to look at him and remember what he was when he was younger. He was beautiful when he famously appeared, dressed in white, to light the Olympic flame signaling the start of the 1996 Atlanta Summer Games, his right hand gripping the torch, his left hand gripped by tremors. His refusal to hide his disease away from the public was, in its own way, an exceedingly beautiful thing.

He was beautiful at the end of his life, wearing sunglasses in the rare times he appeared in public over the past year - motionless, expressionless. There was always a hand on his shoulder - often that of Lonnie Ali, his fourth wife - whether to comfort him or steady him. The way she cared for him in those late stages was nothing if not beautiful.

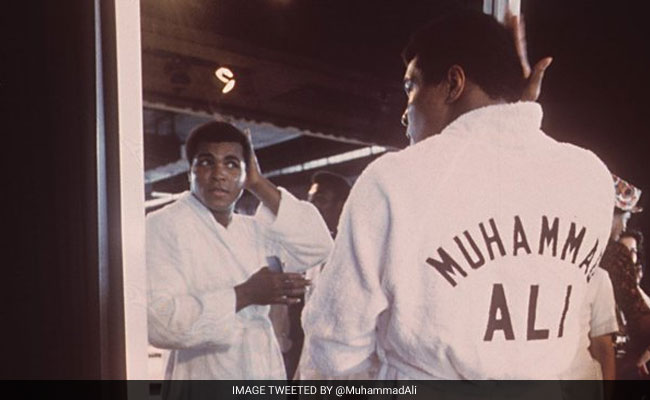

Nobody has ever spread their beauty around more generously or effectively. Ali was so photogenic, he turned photographers into household names. He has inspired more great sportswriting than anyone else in history. Norman Mailer, Davis Miller and David Remnick penned books on him. Ali's own immense charisma could - and did - carry a feature documentary film, but when Hollywood did the Ali story, they got Will Smith to play him.

"For all his verbal gifts, Ali was first a supreme physical performer and sexual presence," Remnick wrote in a 1998 New Yorker profile. "'Ain't I pretty?' he would ask over and over again, and of course, he was. If he'd had the face of Sonny Liston, he would've lost much of his appeal."

Ali changed boxing, eliminating the notion that heavyweights had to be slow-footed and lumbering, but more than that, he changed America. His radical-for-his-day stances on race relations, his embrace of the Nation of Islam, and the Vietnam War, which he opposed, made him perhaps the most visible symbol of the social upheaval that defined the 1960s.

"One of the reasons the civil rights movement went forward was that black people were able to overcome their fear," television commentator Bryant Gumbel once said. "And I honestly believe that, for many black Americans, that came from watching Muhammad Ali. He simply refused to be afraid. And being that way, he gave other people courage."

White America, including the sportswriters who covered his career, didn't quite know what to make of him. And while some people called him traitor - or worse - others came to see him a martyr, as when his refusal to fight in Vietnam cost him the heavyweight title, which was stripped from him in 1967.

His life wasn't always tidy or exemplary. Plenty of people were put off by the bragging, the boasting, the sheer volume of what came out of his mouth. "It's hard to be humble when you're as great as I am," he once said. "I should be a postage stamp," he said another time. "That's the only way I'll ever get licked." In the racially codified language of the time, Ali's behavior was seen as "undignified" and full of "bombast."

He could be downright ugly, as when he called Frazier, his archrival, a "gorilla" and an "Uncle Tom." And that's to say nothing of the major issues that made him so divisive for the generations that came of age with him and before him - the embrace of the Black Muslim movement, the refusal to go to Vietnam.

He could be downright ugly, as when he called Frazier, his archrival, a "gorilla" and an "Uncle Tom." And that's to say nothing of the major issues that made him so divisive for the generations that came of age with him and before him - the embrace of the Black Muslim movement, the refusal to go to Vietnam.

"I ain't got nothing against them Viet Congs," he said by way of explanation.

That was the great dichotomy of Ali. He may have hated war, but he was a fighter, his era's greatest practitioner of a sport whose purpose is to inflict pain upon one's opponent, a sport filled with blood, fixed fights and desperate people. Like boxing, Ali wasn't always pretty.

But he was always, from the beginning until the end, beautiful.

© 2016 The Washington Post

"After a 32-year battle with Parkinson's disease, Muhammad Ali has passed away. . . . The three-time World Heavyweight Champion boxer died this evening," Bob Gunnell, a family spokesman, told NBC News.

Ali may not have been the world's greatest athlete, or even the best boxer of all time - though he is certainly in both discussions. What is indisputable, though, is he was the most beautiful athlete we had ever seen, and likely ever will again - beautiful not so much in the common sense of physical attraction, but in the classical sense, the platonic sense.

The US Army measured Ali's IQ at 78. In his autobiography he said, "I only said I was the greatest, not the smartest."

The camera loved him almost as much as people did.

Ali was beautiful when he smiled, which was often, and beautiful in anger - real or mock. He was beautiful in his youth - as Cassius Clay, son of Louisville, a teenaged Olympic champion, before the decision to turn pro, the conversion to Islam and the change of name - and he was beautiful as an old man, shadow-boxing for the cameras the way old ex-champs are supposed to do, or doing magic tricks for the kids.

Muhammad Ali's first professional fight was a six-round decision in 1960 over Tunney Hunsaker, whose day job was police chief of Fayetteville, West Virginia.

He was beautiful at the end of his life, wearing sunglasses in the rare times he appeared in public over the past year - motionless, expressionless. There was always a hand on his shoulder - often that of Lonnie Ali, his fourth wife - whether to comfort him or steady him. The way she cared for him in those late stages was nothing if not beautiful.

Nobody has ever spread their beauty around more generously or effectively. Ali was so photogenic, he turned photographers into household names. He has inspired more great sportswriting than anyone else in history. Norman Mailer, Davis Miller and David Remnick penned books on him. Ali's own immense charisma could - and did - carry a feature documentary film, but when Hollywood did the Ali story, they got Will Smith to play him.

"For all his verbal gifts, Ali was first a supreme physical performer and sexual presence," Remnick wrote in a 1998 New Yorker profile. "'Ain't I pretty?' he would ask over and over again, and of course, he was. If he'd had the face of Sonny Liston, he would've lost much of his appeal."

Ali changed boxing, eliminating the notion that heavyweights had to be slow-footed and lumbering, but more than that, he changed America. His radical-for-his-day stances on race relations, his embrace of the Nation of Islam, and the Vietnam War, which he opposed, made him perhaps the most visible symbol of the social upheaval that defined the 1960s.

"One of the reasons the civil rights movement went forward was that black people were able to overcome their fear," television commentator Bryant Gumbel once said. "And I honestly believe that, for many black Americans, that came from watching Muhammad Ali. He simply refused to be afraid. And being that way, he gave other people courage."

White America, including the sportswriters who covered his career, didn't quite know what to make of him. And while some people called him traitor - or worse - others came to see him a martyr, as when his refusal to fight in Vietnam cost him the heavyweight title, which was stripped from him in 1967.

His life wasn't always tidy or exemplary. Plenty of people were put off by the bragging, the boasting, the sheer volume of what came out of his mouth. "It's hard to be humble when you're as great as I am," he once said. "I should be a postage stamp," he said another time. "That's the only way I'll ever get licked." In the racially codified language of the time, Ali's behavior was seen as "undignified" and full of "bombast."

In 1984, the boxing legend was diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome that apparently was linked to his career.

"I ain't got nothing against them Viet Congs," he said by way of explanation.

That was the great dichotomy of Ali. He may have hated war, but he was a fighter, his era's greatest practitioner of a sport whose purpose is to inflict pain upon one's opponent, a sport filled with blood, fixed fights and desperate people. Like boxing, Ali wasn't always pretty.

But he was always, from the beginning until the end, beautiful.

© 2016 The Washington Post

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world