Meteorite from Mars that scientists initially-thought contained traces of alien organisms

The Saglek Block rocks of northern Labrador have been submerged beneath water, sucked into Earth's interior, twisted, squeezed and torn by tectonic forces, wrenched upward, weathered by wind and waves, and otherwise subjected to every imaginable form of battering a piece of stone can endure in the course of 3.95 billion years.

Yet a team of scientists believes that carbon atoms within those Canadian rocks provide persisting proof that tiny organisms once dwelled there.

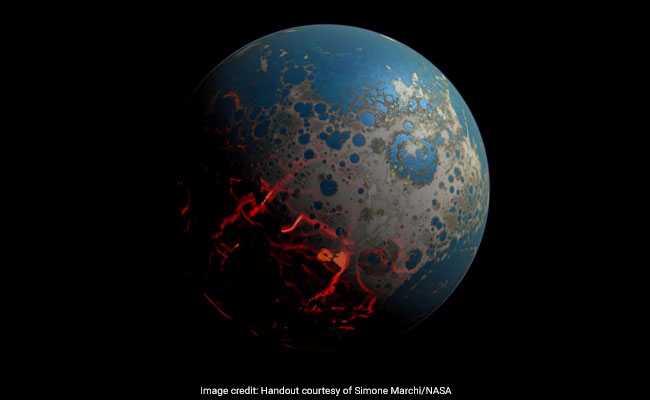

If their analysis, published this week in the journal Nature, is correct, then the rocks contain some of the oldest signs of life on Earth. The discovery would push the origins of life even deeper into the planet's history, to a hellish time when Earth was barely cooled and constantly colliding with other bodies in the solar system. It would mean that biology got started quickly and is even more resilient than we know.

Not all researchers are convinced, though.

This story might sound familiar. In the past 13 months, studies have come out about tiny 3.77 billion-year-old rock tubes and 3.7 billion-year-old microbial mats that also laid a disputed claim to the title "oldest evidence of life." The full debate goes back decades, and scientists still don't agree on what kind of evidence - and how much of it - is necessary to demonstrate that something is a fossil and not just a funny-looking stone.

The distinction is important, because this is about more than just earning a spot in records books, says NASA astrobiologist Abigail Allwood. One day, scientists may have the same debate over structures in a rock sample from another planet.

"For a discovery of such an extraordinary kind, you'd have to be 10 times as rigorous as you'd be on Earth," Allwood said. "If we're going to take the lessons learned and approaches developed on Earth to a place like Mars, we have to get it right."

Earth is ever changing. Though our planet has been around for about 4.5 billion years, most rocks are far younger, thanks to tectonic activity that sucks old stone back into the mantle and remelts it. There are only a few places where scientists still can find stone that was around at Earth's beginning: Greenland, western Australia and the northernmost parts of Canada.

That last site is where University of Tokyo researcher Tsuyoshi Komiya and his colleagues found their samples - 3.95 billion-year-old rocks containing microscopic globs and nodules of graphite, which forms when carbon is heated and squeezed in Earth's interior. Careful analysis in the lab revealed something special about this graphite: It consisted mostly of the isotope carbon 12.

That last site is where University of Tokyo researcher Tsuyoshi Komiya and his colleagues found their samples - 3.95 billion-year-old rocks containing microscopic globs and nodules of graphite, which forms when carbon is heated and squeezed in Earth's interior. Careful analysis in the lab revealed something special about this graphite: It consisted mostly of the isotope carbon 12.

Isotopes, often referred to as "flavors" of an element, are distinguished by their weight. Carbon 12, which has six protons and six neutrons in its nucleus, is lighter than carbon 13, which carries an extra neutron. Though both forms exist in nature, living things prefer the lighter isotope, which is easier to incorporate into molecules. For that reason, when scientists find a mass of graphite that's dominated by carbon 12, they can guess that a long-dead organism was responsible.

"This is a biogenic signature," Komiya said via email.

Though the rocks containing these graphite globs had taken a brutal beating from millennia spent in the planet's interior, they originally formed in gentler conditions at the bottom of an ocean, laid down grain by grain. This indicates that the organisms that formed the graphite were sea-dwellers and that they'd already exploited the tumultuous environment, Komiya says. Not only that, but they had been able to withstand the cataclysm of the "late heavy bombardment," when an extraordinary number of asteroids pummeled Earth and other planets about 4 billion years ago.

"If you manage to form life under these conditions, it has something very profound to say about the resilience and capability of life to start on this planet," said Matthew Dodd, a biogeochemist at University College London, who was not involved in the Nature paper.

The discovery could also guide the search for life on Mars. At the time these rocks were forming, scientists believe, Mars looked very similar to Earth - and even had liquid water. If life existed here, then it might have cropped up there, as well.

"We can use the terrestrial record to guide where [and] what sort of environments to look for the signatures of life," said Allwood, who was not involved in the latest research. Studies like Komiya's are being considered by the NASA scientists picking landing sites for the Mars 2020 rover, which is designed to seek out ancient microbial life.

Dodd is working on some ancient samples of his own. In March, he and several colleagues reported a related finding in Nature: 3.77 billion-year-old rocks uncovered in another part of northern Canada that contained straw-shaped "microfossils."

But publishing a paper, for Dodd, Komiya and anyone purporting to have found evidence of oldest life, is only the beginning. Dodd said outside teams have requested his samples, some to verify the age of the rocks, others to test for potential non-biological explanations for the microfossils.

He expects his colleagues will want to do the same thing with Komiya's rocks. They'll test for other elements associated with biology, like phosphorus and sulfur. They'll also look for alternative explanations for the high concentration of carbon 12. Allwood said this abundance could have been created by hydrothermal activity, then transported later into Komiya's samples - a possibility she felt his paper didn't fully address.

"Simply just reporting isotopically light carbon doesn't give you early life," Dodd said. "They're going to face a lot of controversy, a lot of disputes."

Such studies always do. Both Dodd and Allwood mentioned the case of Allan Hills 84001, a meteorite from Mars that scientists initially thought contained traces of alien organisms. At a 1996 news conference, President Bill Clinton said the implications of the discovery - if confirmed - "are as far-reaching and awe-inspiring as can be imagined."

But that confirmation didn't come. Instead, the supposed signs of life were explained by other forces, both natural and man-made. Now, Allan Hills 84001 is considered a cautionary tale for scientists seeking ancient life on Earth and elsewhere.

Dodd describes these debates as an integral feature of the scientific process.

"Why is this so controversial? It's one of the biggest questions mankind has asked itself - where did we come from and how did we get here?" he said. "It's good to see these arguments happening in the conferences because it moves science forward. If you don't have the confrontation, you don't learn anything."

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Yet a team of scientists believes that carbon atoms within those Canadian rocks provide persisting proof that tiny organisms once dwelled there.

If their analysis, published this week in the journal Nature, is correct, then the rocks contain some of the oldest signs of life on Earth. The discovery would push the origins of life even deeper into the planet's history, to a hellish time when Earth was barely cooled and constantly colliding with other bodies in the solar system. It would mean that biology got started quickly and is even more resilient than we know.

Not all researchers are convinced, though.

This story might sound familiar. In the past 13 months, studies have come out about tiny 3.77 billion-year-old rock tubes and 3.7 billion-year-old microbial mats that also laid a disputed claim to the title "oldest evidence of life." The full debate goes back decades, and scientists still don't agree on what kind of evidence - and how much of it - is necessary to demonstrate that something is a fossil and not just a funny-looking stone.

The distinction is important, because this is about more than just earning a spot in records books, says NASA astrobiologist Abigail Allwood. One day, scientists may have the same debate over structures in a rock sample from another planet.

"For a discovery of such an extraordinary kind, you'd have to be 10 times as rigorous as you'd be on Earth," Allwood said. "If we're going to take the lessons learned and approaches developed on Earth to a place like Mars, we have to get it right."

Earth is ever changing. Though our planet has been around for about 4.5 billion years, most rocks are far younger, thanks to tectonic activity that sucks old stone back into the mantle and remelts it. There are only a few places where scientists still can find stone that was around at Earth's beginning: Greenland, western Australia and the northernmost parts of Canada.

An artist's conception of early Earth, with it's surface pummeled by asteroids.

Isotopes, often referred to as "flavors" of an element, are distinguished by their weight. Carbon 12, which has six protons and six neutrons in its nucleus, is lighter than carbon 13, which carries an extra neutron. Though both forms exist in nature, living things prefer the lighter isotope, which is easier to incorporate into molecules. For that reason, when scientists find a mass of graphite that's dominated by carbon 12, they can guess that a long-dead organism was responsible.

"This is a biogenic signature," Komiya said via email.

Though the rocks containing these graphite globs had taken a brutal beating from millennia spent in the planet's interior, they originally formed in gentler conditions at the bottom of an ocean, laid down grain by grain. This indicates that the organisms that formed the graphite were sea-dwellers and that they'd already exploited the tumultuous environment, Komiya says. Not only that, but they had been able to withstand the cataclysm of the "late heavy bombardment," when an extraordinary number of asteroids pummeled Earth and other planets about 4 billion years ago.

"If you manage to form life under these conditions, it has something very profound to say about the resilience and capability of life to start on this planet," said Matthew Dodd, a biogeochemist at University College London, who was not involved in the Nature paper.

The discovery could also guide the search for life on Mars. At the time these rocks were forming, scientists believe, Mars looked very similar to Earth - and even had liquid water. If life existed here, then it might have cropped up there, as well.

"We can use the terrestrial record to guide where [and] what sort of environments to look for the signatures of life," said Allwood, who was not involved in the latest research. Studies like Komiya's are being considered by the NASA scientists picking landing sites for the Mars 2020 rover, which is designed to seek out ancient microbial life.

Dodd is working on some ancient samples of his own. In March, he and several colleagues reported a related finding in Nature: 3.77 billion-year-old rocks uncovered in another part of northern Canada that contained straw-shaped "microfossils."

But publishing a paper, for Dodd, Komiya and anyone purporting to have found evidence of oldest life, is only the beginning. Dodd said outside teams have requested his samples, some to verify the age of the rocks, others to test for potential non-biological explanations for the microfossils.

He expects his colleagues will want to do the same thing with Komiya's rocks. They'll test for other elements associated with biology, like phosphorus and sulfur. They'll also look for alternative explanations for the high concentration of carbon 12. Allwood said this abundance could have been created by hydrothermal activity, then transported later into Komiya's samples - a possibility she felt his paper didn't fully address.

"Simply just reporting isotopically light carbon doesn't give you early life," Dodd said. "They're going to face a lot of controversy, a lot of disputes."

Such studies always do. Both Dodd and Allwood mentioned the case of Allan Hills 84001, a meteorite from Mars that scientists initially thought contained traces of alien organisms. At a 1996 news conference, President Bill Clinton said the implications of the discovery - if confirmed - "are as far-reaching and awe-inspiring as can be imagined."

But that confirmation didn't come. Instead, the supposed signs of life were explained by other forces, both natural and man-made. Now, Allan Hills 84001 is considered a cautionary tale for scientists seeking ancient life on Earth and elsewhere.

Dodd describes these debates as an integral feature of the scientific process.

"Why is this so controversial? It's one of the biggest questions mankind has asked itself - where did we come from and how did we get here?" he said. "It's good to see these arguments happening in the conferences because it moves science forward. If you don't have the confrontation, you don't learn anything."

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)