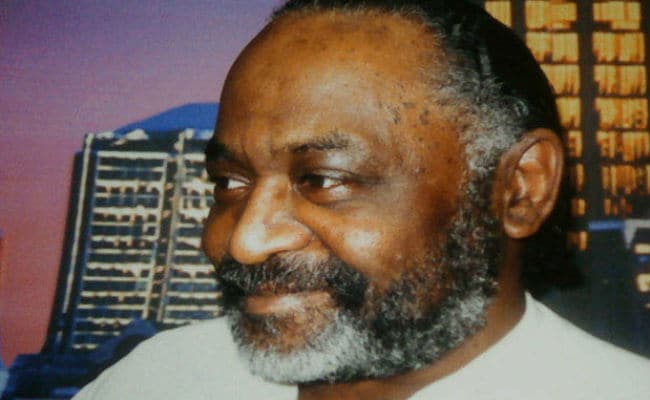

Ray Gray-Present Day. Photo: Courtesy of the Gray Family. (Reuters Photo)

Nightmares don't just happen on Elm Street. Raymond "Ray" Gray's nightmare began on Euclid Street in Detroit.

Twenty-one years-old, Gray stood 5 feet 7 inches and 123 pounds. He had long, straight hair and a full fu manchu mustache. An African-American with a light complexion, he was an amateur Golden Gloves boxer with a big right-hand. About to go professional, Gray was being trained by Emmanuel Steward. A legendary fight trainer, Steward also trained world champion, Thomas "the Hit Man" Hearns.

An artist too, Gray figured the money he made boxing would pay for art school. Among his many talents, Gray liked to cut hair. His future looked bright.

On the afternoon of February 6, 1973, Sandy Smith came over to his house. Smith was there for a dress fitting with his sister Darlene and a haircut from Gray. First though, he began to draw her.

Friends Leonard Jones and Terry Staples were shooting pool in the basement. Suddenly, Barbara Hill, Gray's former girlfriend, showed up with friends Tyrone Pugh and Charlie Matthews.

Matthews was 5 feet 5 inches with a mustache and dark complexion. He wore a hat. Pugh was tall with a knit hat and short leather jacket. Convicted felons, what Gray didn't know was that they were a Mutt and Jeff team of stick-up artists. Pugh and Matthews claimed they wanted to score some heroin.

Arrested once for smoking a joint, Gray wasn't into drugs. An athlete, he had no idea where to get it.

"I'll take 'em to Ruben's," Hill offered.

Ruben Bryant was a known drug dealer that Hill's brother hung out with. Gray continued to cut Sandy's hair and stayed home the rest of the day and night, while the trio went to Bryant's drug den on Euclid Street. When they got there, Hill went in. Alone.

Upstairs in the apartment with Hill were Bryant, his girlfriend Marie Clark, and friend Jacqueline Hall. Minutes later, two men tried breaking into the apartment. Hall later told police that Hill pushed her out of the way and opened the apartment door. The men rushed in.

"Ty, stay back there, I can watch them," said the shorter of the two men, brandishing a nickel-plated revolver.

"Get down with your back on the floor," Pugh ordered Bryant.

Instead, Bryant pushed a small table toward the gunman. A boxer with a big right hand would have taken Bryant out with one punch.

Instead, they struggled, until the gunman shot him dead. Then, the gunman went into the bedroom.

As Jacqueline Hall watched, he took a watch, paper money, and change from a jar. Then the murderers made their escape. That night, Hill called Gray. She was with the police downtown.

"Ruben was killed during a robbery!" she cried.

She hung up. An hour later, the cops dropped Hill at Gray's house.

She told Gray that as she was leaving Bryant's apartment, two dudes burst in and shot him.

"Wait, what about the two guys you were with?" Gray asked.

Hill never answered. Two days later, a detective was interviewing her. Cognizant that she had been dropped at her boyfriend's apartment, he asked the obvious.

"Who's your boyfriend?"

In fact, they had broken up months before. But Hill still fingered Gray. The police chose not to investigate Gray's whereabouts. They had no suspects. But Hill had just given them one. To white cops in 1973 Detroit, one black man was the same as another.

What else Hill may have said about Gray is unknown. Later that day, a friend was driving Gray home from the gym, because he didn't drive. When Gray got there, he saw police cars. His sister Darlene's boyfriend was in handcuffs. A cop looked at Gray's mug shot in his hand from the weed bust, then up at Gray.

"We got the wrong nigger," he told his partner.

The handcuffs were transferred to Gray. Despite lack of motive, means, and opportunity, Ray Gray was arrested and charged with Bryant's murder. Moreover, the police didn't even bother to search his house for any evidence, including the murder weapon or loot from the robbery, which were never recovered.

"What about fingerprints?" Gray asked the arresting officer on the way downtown.

In fact, they had lifted a print off the jar from Bryant's bedroom that contained money and that Clark said one the gunman had touched. It didn't match Gray's. But they didn't tell him that.

"I was brought to the station and placed in a holding cell with about nine other men. It smelled from cigarette smoke, alcohol, urine and throw-up from those who were going through withdrawal from substance abuse. About 45 minutes later, a detective came and escorted me to an isolated part of the jail, and I was placed in an empty holding cell," Gray recalls.

That's when Michael Bryant showed up. The dead man's brother, he was also a police cadet. He spoke to Gray through the bars.

"You're going down for my brother's murder," Michael Bryant said calmly. "We're doing a lineup."

"I didn't do it. I wasn't even there. I'm very sure I won't be picked out," Gray answered.

Michael Bryant smiled.

"I'm 100% sure you will be," the police cadet said and left.

In another section of the jail, a detective sergeant did what police call a throwdown. They placed photographs on a table and showed them to Clark and Hall. Both said Gray's photograph, "Looks like the man," the gunman.

Gray was the only person in the throwdown with a mustache similar to the gunman. Then it was time for the live lineup.

"I walk out to a prearranged lineup that the police had put together," Gray continues.

Gray was the only bantamweight; the other five men were bigger and heavier.

"I was placed next to the tallest guy in the lineup and was the only one with any hair whatsoever on their face, let alone a mustache. I was completely stunned at the results."

Hall and Clark identified Gray as the shooter. It didn't make any difference to police that Hall was Bryant's girlfriend. Gray was charged with first-degree felony murder. Richard Monash, his neophyte attorney, not only convinced Gray to request a bench trial without a jury, he never objected when the state denied Gray discovery of exculpatory evidence.

During the trial in front of Judge Irving Ravitz, Monash questioned Hall, who now lives in Georgia and goes by the last name of Cody.

Monash showed her the photos police used for the throwdown.

"In all these photographs, is there anybody in there who has the type of mustache you believe you saw that evening?" Monash asked her.

"Uh huh, yes," Hall answered.

"How many of the pictures have the type of mustache you believe you saw that evening?"

"One."

"Do you recognize that face in the photograph?"

"Yes."

"Who is that person?" Monash continued.

"The guy sitting there," Hall said, pointing out Gray at the defense table.

Monash, who had just proven the throwdown was fixed, also questioned Barbara Hill. She testified that Gray was not one of the holdup men. Monash then produced his alibi witnesses - Sandy Smith, Darlene Gray, Leonard Jones, and Terry Staples.

All four testified Gray was home at the time of the robbery. Gray himself took the stand and testified to the same. Without explaining why, Judge Ravitz said he didn't believe any of them. He found Gray guilty of first-degree felony murder and sentenced him to life in prison, where Gray continued to paint.

He met art teacher, Barbara Rinehart, who taught prisoners. They fell in love and married.

In 1980, Gray saw Charlie Matthews, who had been at his house that day looking for heroin, in the prison yard. Matthews had just come inside for an unrelated crime and was surprised to see Gray.

"I'm here because they think I'm you," Gray told him.

"Tyrone shot Ruben. I touched some things that were not taken out of the apartment, where I figured I had left prints," Matthews claimed.

Gray convinced him to come forward with the truth. Matthews agreed. Matthews executed an affidavit, in which he stated that he, along with Tyrone Pugh, went into the apartment for the purpose of robbing Ruben Bryant, the drug dealer. Matthews further stated that Bryant was shot by the taller individual, his buddy Tyrone Pugh.

In December 1983, Gray's new attorney John Allen Johnson brought the matter to the attention of Judge Ravitz. Johnson requested a new trial, and Ravitz held a hearing. Matthews took the stand. He testified under oath that he had firsthand knowledge of the murder.

He also testified that Gray was not present at the crime scene.

The district attorney cautioned him. If he went further and admitted to culpability, he would be charged with murder. Matthews asked for immunity in exchange for his further testimony. Not interested in the truth, the state of Michigan denied his request.

Whipsawed, Matthews had no choice. Afraid of being charged with murder, Matthews exercised his Fifth Amendment rights to self-incrimination and kept his mouth shut. The questioning ceased, the affidavit was never introduced, and Gray's motion for a new trial was denied by Ravitz.

Gray went back to his cell, to paint and wait for someone to get at the truth. His was a nightmare that even Freddy Krueger couldn't create.

On October 13, 2005, Gray's third attorney, Craig Daly, filed a Motion for Relief of Judgment. It was based on newly discovered exculpatory evidence as a result of a FOIA request. It showed what the prosecution had hidden behind their backs since the 1973 trial.

The Investigator's Report file fails to mention any fingerprints taken from the jar at the crime scene. But hidden in the file was indeed mention that prints were lifted off the jar that didn't match Gray's.

No mention was made if they matched Matthews or Pugh's.

Despite this damning evidence of a police cover-up, the court denied the Motion for Relief on September 22, 2005. Five years later on June 17, 2010, Ray Gray was finally granted a public parole hearing, his first. Shackled from waist to ankles, he testified before parole board member Miguel Barrios.

This reporter was an eyewitness at that hearing.

Michigan's own rules state that a parole is not supposed to be about guilt or innocence, but rather what the individual has done behind bars - Gray had become a renowned artist and mentor to other prisoners - and what he will do when he gets out. Yet Barrios chose to concentrate on Gray's continued protestations of innocence.

With many witnesses present in the packed hearing room, Barrios verbally abused Gray for daring to maintain his innocence. Barrios screamed at him incessantly, trying to browbeat a confession out of Gray.

"I couldn't stand to watch it," says Barbe Gray in tears. "I had to walk out."

During the hearing, Gray's parole officer turned to this reporter and said, "The harder they are at the hearing, the better the chance they get out."

Not in Gray's case. In December 2010, the parole board voted unanimously to deny Gray a commutation of his sentence. Once again, he went back to his cell to wait for justice, while he painted.

"The art has helped me in many ways, for it allows me to express some of my deepest inner feelings and on another level, created a world much different from this one, a form of escapism I suppose," said Gray. "However, I try to address world events also despite where I'm at, to still try and be aware of what's going on in the world at large.

"To know that some of my work is on people's wall that I don't even know, some in other countries, is a good feeling and that by way of my art, I was able to meet and marry my Barbe. I'm thankful for that."

It is because of a fixed lineup that Ray Gray is currently in his 43rd year behind bars for a murder he didn't commit.

"I would welcome my picture being next to Charlie and Tyrone [now deceased] and whoever else," Gray continues.

Ray Gray's nightmare has now gone on for 43 years. A petition requesting that Michigan Governor Rick Snyder pardon Gray has just begun circulating on social media. It will be attached to Ray Gray's new request for a hearing to free him.

This story was originally featured on The-Line-Up.com. The Lineup is the premier digital destination for fans of true crime, horror, the mysterious, and the paranormal.

Twenty-one years-old, Gray stood 5 feet 7 inches and 123 pounds. He had long, straight hair and a full fu manchu mustache. An African-American with a light complexion, he was an amateur Golden Gloves boxer with a big right-hand. About to go professional, Gray was being trained by Emmanuel Steward. A legendary fight trainer, Steward also trained world champion, Thomas "the Hit Man" Hearns.

An artist too, Gray figured the money he made boxing would pay for art school. Among his many talents, Gray liked to cut hair. His future looked bright.

On the afternoon of February 6, 1973, Sandy Smith came over to his house. Smith was there for a dress fitting with his sister Darlene and a haircut from Gray. First though, he began to draw her.

Friends Leonard Jones and Terry Staples were shooting pool in the basement. Suddenly, Barbara Hill, Gray's former girlfriend, showed up with friends Tyrone Pugh and Charlie Matthews.

Matthews was 5 feet 5 inches with a mustache and dark complexion. He wore a hat. Pugh was tall with a knit hat and short leather jacket. Convicted felons, what Gray didn't know was that they were a Mutt and Jeff team of stick-up artists. Pugh and Matthews claimed they wanted to score some heroin.

Arrested once for smoking a joint, Gray wasn't into drugs. An athlete, he had no idea where to get it.

"I'll take 'em to Ruben's," Hill offered.

Ruben Bryant was a known drug dealer that Hill's brother hung out with. Gray continued to cut Sandy's hair and stayed home the rest of the day and night, while the trio went to Bryant's drug den on Euclid Street. When they got there, Hill went in. Alone.

Upstairs in the apartment with Hill were Bryant, his girlfriend Marie Clark, and friend Jacqueline Hall. Minutes later, two men tried breaking into the apartment. Hall later told police that Hill pushed her out of the way and opened the apartment door. The men rushed in.

"Ty, stay back there, I can watch them," said the shorter of the two men, brandishing a nickel-plated revolver.

"Get down with your back on the floor," Pugh ordered Bryant.

Instead, Bryant pushed a small table toward the gunman. A boxer with a big right hand would have taken Bryant out with one punch.

Instead, they struggled, until the gunman shot him dead. Then, the gunman went into the bedroom.

As Jacqueline Hall watched, he took a watch, paper money, and change from a jar. Then the murderers made their escape. That night, Hill called Gray. She was with the police downtown.

"Ruben was killed during a robbery!" she cried.

She hung up. An hour later, the cops dropped Hill at Gray's house.

She told Gray that as she was leaving Bryant's apartment, two dudes burst in and shot him.

"Wait, what about the two guys you were with?" Gray asked.

Hill never answered. Two days later, a detective was interviewing her. Cognizant that she had been dropped at her boyfriend's apartment, he asked the obvious.

"Who's your boyfriend?"

In fact, they had broken up months before. But Hill still fingered Gray. The police chose not to investigate Gray's whereabouts. They had no suspects. But Hill had just given them one. To white cops in 1973 Detroit, one black man was the same as another.

What else Hill may have said about Gray is unknown. Later that day, a friend was driving Gray home from the gym, because he didn't drive. When Gray got there, he saw police cars. His sister Darlene's boyfriend was in handcuffs. A cop looked at Gray's mug shot in his hand from the weed bust, then up at Gray.

"We got the wrong nigger," he told his partner.

The handcuffs were transferred to Gray. Despite lack of motive, means, and opportunity, Ray Gray was arrested and charged with Bryant's murder. Moreover, the police didn't even bother to search his house for any evidence, including the murder weapon or loot from the robbery, which were never recovered.

"What about fingerprints?" Gray asked the arresting officer on the way downtown.

In fact, they had lifted a print off the jar from Bryant's bedroom that contained money and that Clark said one the gunman had touched. It didn't match Gray's. But they didn't tell him that.

"I was brought to the station and placed in a holding cell with about nine other men. It smelled from cigarette smoke, alcohol, urine and throw-up from those who were going through withdrawal from substance abuse. About 45 minutes later, a detective came and escorted me to an isolated part of the jail, and I was placed in an empty holding cell," Gray recalls.

That's when Michael Bryant showed up. The dead man's brother, he was also a police cadet. He spoke to Gray through the bars.

"You're going down for my brother's murder," Michael Bryant said calmly. "We're doing a lineup."

"I didn't do it. I wasn't even there. I'm very sure I won't be picked out," Gray answered.

Michael Bryant smiled.

"I'm 100% sure you will be," the police cadet said and left.

In another section of the jail, a detective sergeant did what police call a throwdown. They placed photographs on a table and showed them to Clark and Hall. Both said Gray's photograph, "Looks like the man," the gunman.

Gray was the only person in the throwdown with a mustache similar to the gunman. Then it was time for the live lineup.

"I walk out to a prearranged lineup that the police had put together," Gray continues.

Gray was the only bantamweight; the other five men were bigger and heavier.

"I was placed next to the tallest guy in the lineup and was the only one with any hair whatsoever on their face, let alone a mustache. I was completely stunned at the results."

Hall and Clark identified Gray as the shooter. It didn't make any difference to police that Hall was Bryant's girlfriend. Gray was charged with first-degree felony murder. Richard Monash, his neophyte attorney, not only convinced Gray to request a bench trial without a jury, he never objected when the state denied Gray discovery of exculpatory evidence.

During the trial in front of Judge Irving Ravitz, Monash questioned Hall, who now lives in Georgia and goes by the last name of Cody.

Monash showed her the photos police used for the throwdown.

"In all these photographs, is there anybody in there who has the type of mustache you believe you saw that evening?" Monash asked her.

"Uh huh, yes," Hall answered.

"How many of the pictures have the type of mustache you believe you saw that evening?"

"One."

"Do you recognize that face in the photograph?"

"Yes."

"Who is that person?" Monash continued.

"The guy sitting there," Hall said, pointing out Gray at the defense table.

Monash, who had just proven the throwdown was fixed, also questioned Barbara Hill. She testified that Gray was not one of the holdup men. Monash then produced his alibi witnesses - Sandy Smith, Darlene Gray, Leonard Jones, and Terry Staples.

All four testified Gray was home at the time of the robbery. Gray himself took the stand and testified to the same. Without explaining why, Judge Ravitz said he didn't believe any of them. He found Gray guilty of first-degree felony murder and sentenced him to life in prison, where Gray continued to paint.

He met art teacher, Barbara Rinehart, who taught prisoners. They fell in love and married.

In 1980, Gray saw Charlie Matthews, who had been at his house that day looking for heroin, in the prison yard. Matthews had just come inside for an unrelated crime and was surprised to see Gray.

"I'm here because they think I'm you," Gray told him.

"Tyrone shot Ruben. I touched some things that were not taken out of the apartment, where I figured I had left prints," Matthews claimed.

Gray convinced him to come forward with the truth. Matthews agreed. Matthews executed an affidavit, in which he stated that he, along with Tyrone Pugh, went into the apartment for the purpose of robbing Ruben Bryant, the drug dealer. Matthews further stated that Bryant was shot by the taller individual, his buddy Tyrone Pugh.

In December 1983, Gray's new attorney John Allen Johnson brought the matter to the attention of Judge Ravitz. Johnson requested a new trial, and Ravitz held a hearing. Matthews took the stand. He testified under oath that he had firsthand knowledge of the murder.

He also testified that Gray was not present at the crime scene.

The district attorney cautioned him. If he went further and admitted to culpability, he would be charged with murder. Matthews asked for immunity in exchange for his further testimony. Not interested in the truth, the state of Michigan denied his request.

Whipsawed, Matthews had no choice. Afraid of being charged with murder, Matthews exercised his Fifth Amendment rights to self-incrimination and kept his mouth shut. The questioning ceased, the affidavit was never introduced, and Gray's motion for a new trial was denied by Ravitz.

Gray went back to his cell, to paint and wait for someone to get at the truth. His was a nightmare that even Freddy Krueger couldn't create.

On October 13, 2005, Gray's third attorney, Craig Daly, filed a Motion for Relief of Judgment. It was based on newly discovered exculpatory evidence as a result of a FOIA request. It showed what the prosecution had hidden behind their backs since the 1973 trial.

The Investigator's Report file fails to mention any fingerprints taken from the jar at the crime scene. But hidden in the file was indeed mention that prints were lifted off the jar that didn't match Gray's.

No mention was made if they matched Matthews or Pugh's.

Despite this damning evidence of a police cover-up, the court denied the Motion for Relief on September 22, 2005. Five years later on June 17, 2010, Ray Gray was finally granted a public parole hearing, his first. Shackled from waist to ankles, he testified before parole board member Miguel Barrios.

This reporter was an eyewitness at that hearing.

Michigan's own rules state that a parole is not supposed to be about guilt or innocence, but rather what the individual has done behind bars - Gray had become a renowned artist and mentor to other prisoners - and what he will do when he gets out. Yet Barrios chose to concentrate on Gray's continued protestations of innocence.

With many witnesses present in the packed hearing room, Barrios verbally abused Gray for daring to maintain his innocence. Barrios screamed at him incessantly, trying to browbeat a confession out of Gray.

"I couldn't stand to watch it," says Barbe Gray in tears. "I had to walk out."

During the hearing, Gray's parole officer turned to this reporter and said, "The harder they are at the hearing, the better the chance they get out."

Not in Gray's case. In December 2010, the parole board voted unanimously to deny Gray a commutation of his sentence. Once again, he went back to his cell to wait for justice, while he painted.

"The art has helped me in many ways, for it allows me to express some of my deepest inner feelings and on another level, created a world much different from this one, a form of escapism I suppose," said Gray. "However, I try to address world events also despite where I'm at, to still try and be aware of what's going on in the world at large.

"To know that some of my work is on people's wall that I don't even know, some in other countries, is a good feeling and that by way of my art, I was able to meet and marry my Barbe. I'm thankful for that."

It is because of a fixed lineup that Ray Gray is currently in his 43rd year behind bars for a murder he didn't commit.

"I would welcome my picture being next to Charlie and Tyrone [now deceased] and whoever else," Gray continues.

Ray Gray's nightmare has now gone on for 43 years. A petition requesting that Michigan Governor Rick Snyder pardon Gray has just begun circulating on social media. It will be attached to Ray Gray's new request for a hearing to free him.

This story was originally featured on The-Line-Up.com. The Lineup is the premier digital destination for fans of true crime, horror, the mysterious, and the paranormal.

© Thomson Reuters 2015

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world