Architect Fernando Romero's imagined "Border City," half in Mexico and half in the United States.

On the wall of Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman's design lab at the University of California at San Diego, there's a giant map made by a group of former students. The map shows an unnamed region fronted by a broad seaboard and bisected by a perfectly straight line, rendered by the students as a length of yarn. Absent any place names, it's hard to recognize the locale at first, but the string is a clue: This is a chunk of the westernmost portion of the U.S.-Mexico border, running about 15 miles from the Pacific to the mountains. As seen in the map, the border itself is reduced to a mere afterthought, something tacked on, superficial.

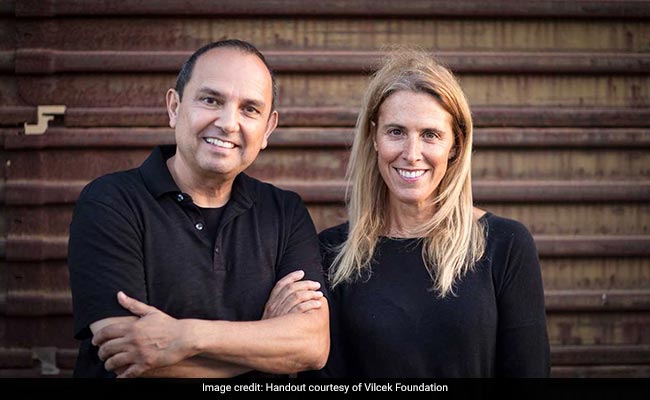

"We call it Mexus," says Cruz. Destined for the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of Architecture - the design world's premier showcase for new ideas, opening this May - Cruz and Forman's Mexus project uses maps, renderings and diagrams to send a pointed political message. As Forman explains, "We've been interested in documenting the flows, invisible and visible, that move back and forth across the border." The duo's exhibition includes ideas both grounded and improbable for turning the region into an integral whole - culturally, economically and ecologically - with a special focus on the area's combined watershed. Mexus, says Cruz, is "a region that contains all the stuff that walls cannot stop."

The pair - one an architect, the other a political scientist - have spent years looking at the border, mostly through conceptual inquiries like Mexus but also through more tangible projects. For instance, their firm has designed Cross-Border Community Stations - outposts developed in partnership with UCSD to foster grass-roots social research - that are underway in San Diego and Tijuana. Together, these projects - from far-sighted to practical - suggest how architecture can provide a counterweight to our current wall-crazed, deportation-frenzied moment by blurring, rather than accentuating, the divisions between the United States and Mexico.

As a field, architecture has long been a uniquely international endeavor, and given the close physical quarters of Mexico and the United States, it seems only natural that the two would cross-pollinate architecturally. Whether through the popular Spanish Colonial-style houses that dot the American suburban landscape or the Mayan-inspired concrete blocks of Frank Lloyd Wright's La Miniatura in Pasadena, California, American architecture has often been preoccupied with Mexico both as a romantic ideal and a source of the new. Meanwhile, designers from the south have frequently picked up on Mexican themes in American design and reimported them, making them their own.

As a field, architecture has long been a uniquely international endeavor, and given the close physical quarters of Mexico and the United States, it seems only natural that the two would cross-pollinate architecturally. Whether through the popular Spanish Colonial-style houses that dot the American suburban landscape or the Mayan-inspired concrete blocks of Frank Lloyd Wright's La Miniatura in Pasadena, California, American architecture has often been preoccupied with Mexico both as a romantic ideal and a source of the new. Meanwhile, designers from the south have frequently picked up on Mexican themes in American design and reimported them, making them their own.

But since the 2016 election, architectural offices on both sides of the border - of all sizes and dispensations, from high-flown academic to high-end commercial - have found themselves in a strange new climate. "We were all thinking that we were leaving a moment of invisibility and moving into a moment of inclusion," says Henry Munoz. "Instead we became a target." The principal (not an architect himself, but CEO) of San Antonio-based design firm Munoz and Co., he also happens to be the finance chairman of the Democratic National Committee and a lifelong activist for Latino and Mexican American causes. Speaking of his personal outlook, he refers to the concept of the "transnational imaginary": not just an identity, but a kind of spatialized mental paradigm, one characterized by "sharing, fluidity, mixed families," and only partially divided by a border that "we didn't cross, but that crossed us."

As applied to architecture, the concept of transnationality can take many forms. In 2005, for instance, Munoz and Co.'s educational complex for the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley featured a glass-enclosed elevator shaft whose etched panels sport traditional Mexican dichos, or proverbs, in both English and Spanish, the two languages mixing increasingly as the elevator ascends. Today, one of Munoz's ongoing projects is a master plan for Brownsville, Texas, a scheme whose primary objective is to transform the city's downtown into a thriving mixed-use district - counteracting the encroachments of border wall construction, which has continued to slice away at the physical fabric of the area.

For contemporary global architects - studios in multiple countries, plane tickets always at the ready - transnationality comes fairly naturally, and ideas continue to flow freely across the border despite the bellicose rhetoric surrounding the immigration debate. This is especially true for an architect like Alfonso Medina, who was born in Texas to Mexican parents and raised primarily in Tijuana. Today he keeps one branch of his firm, T38 Studio, in the famed border town and another in New York City.

In Tijuana, Medina has been responsible for a growing series of residential buildings designed around a "co-living" concept, with small units and shared amenities to reduce housing costs. Tijuana has been, as Medina puts it, a "lab" for this new model, and its success there has acted as a springboard for another similar project in Denver as well as still others the architect is hoping to build around the United States. "In Mexico," he says, "we can actually achieve things [U.S.] developers say we can't."

In Tijuana, Medina has been responsible for a growing series of residential buildings designed around a "co-living" concept, with small units and shared amenities to reduce housing costs. Tijuana has been, as Medina puts it, a "lab" for this new model, and its success there has acted as a springboard for another similar project in Denver as well as still others the architect is hoping to build around the United States. "In Mexico," he says, "we can actually achieve things [U.S.] developers say we can't."

Medina is hardly the only architect whose background transcends the U.S.-Mexico border. Speaking to me from a classic Mexico City traffic jam, architect Frida Escobedo explained her own split architectural identity, working in her native Mexico while teaching in the United States and taking on commissions around the world. "I find it easier to understand some of the ideas about architecture in the U.S. than in Mexico," she says. Her sojourns abroad have allowed her to meet a network of friends and teachers, and led to both small commissions - a pair of subdued boutiques in Florida for cosmetics maker Aesop - and larger ones, most notably the 2018 Serpentine Pavilion, the annual temporary structure in London's Hyde Park that has seen previous iterations from the likes of Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid. Debuting this June, Escobedo's pavilion includes a water feature and a surrounding lattice wall that recalls, in its quiet intimacy, something of old Mexican courtyard houses.

There may be no better example of the ongoing cross-border pollination in architecture than the fact that NASA - arguably the last word in flag-waving all-American-ness - has hired TEN Arquitectos to design a 60,000-square-foot complex for the Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. Founded in Mexico City in 1986, the architecture firm operates a major satellite in New York City. In its NASA project, set to break ground this summer, style definitely takes a back seat; the buildings are a simple ensemble of glass boxes, their reserve in keeping with the client's scientific agenda. But then, TEN Arquitectos, whose workload also includes the new Mexican Museum in San Francisco, has always specialized in a sober-minded functionalism.

"As an architect, you can't just assume because you're one nationality or another that you automatically know what's best," says the principal in charge of the NASA commission, Andrea Steele. She says that the global outlook and mix of cultures at the firm reinforce a process of analysis and engagement, helping them understand cultures as varied as Mexican American curators and Midwestern astrophysicists.

"As an architect, you can't just assume because you're one nationality or another that you automatically know what's best," says the principal in charge of the NASA commission, Andrea Steele. She says that the global outlook and mix of cultures at the firm reinforce a process of analysis and engagement, helping them understand cultures as varied as Mexican American curators and Midwestern astrophysicists.

Yet another architect working at the intersection of U.S. and Mexican culture is Fernando Romero, whose Mexico City-based firm also keeps a shop in Manhattan. While working on the Mexican capital's new airport, Romero has simultaneously been commissioned by Elon Musk to produce a speculative design for the investor's ambitious Hyperloop One high-speed transportation system. In Romero's proposal, the network would create a transnational link between the major cities of northern Mexico and the U.S. side of the border - not a likely prospect for the immediate future, but one that the architect considers well within the realm of the possible.

"We are convinced Mexico is the best partner the U.S. has," Romero says. He's confident that this view will prevail among Americans who are "informed, sensible and have a wider understanding of the realities."

Indeed, Romero - like Cruz and Forman - has also developed a scheme for bridging the physical boundary between the two countries: a visionary "Border City," half in Mexico and half in the United States, which would operate as a seamless whole. Romero has been invested in the subject for a long time. In 2008, he produced a book called "Hyperborder," a sweeping data-packed survey of the whole regional condition. "Border City" appeared eight years later at the London Design Biennale, whose theme was "Utopia by Design." No less far-fetched than the Hyperloop, the project nonetheless shows that despite the challenging times, designers' sense of global mission is still intact, and that the fraught love affair between the United States and Mexico - so often expressed in architecture - has a little life in it yet.

On a recent winter day, Alfonso Medina's sister, Adriana, who is a designer at his firm, gave me a tour of a new Tijuana apartment complex, Arboleda, that caters both to the Mexican creative class and to San Diegans who commute to work in California but are looking for a higher quality of life at lower cost. The building, like many of Medina's in the city, features appliances and fixtures trucked in from across the border.

On a recent winter day, Alfonso Medina's sister, Adriana, who is a designer at his firm, gave me a tour of a new Tijuana apartment complex, Arboleda, that caters both to the Mexican creative class and to San Diegans who commute to work in California but are looking for a higher quality of life at lower cost. The building, like many of Medina's in the city, features appliances and fixtures trucked in from across the border.

We walked into the building's gracious common area, cantilevered dramatically over a hillside with a lush semitropical garden below. Out the window was a dramatic view: miles of houses (most of them, it should be said, considerably less commodious) covering every hillside and lining the river that cut through Cruz and Forman's wall map as a blue strip of masking tape.

To the northeast, just on the far side of the border, was a building site for prototype segments for the proposed border wall, the permanent, 30-foot-high concrete barrier that may one day run between Mexico and the United States. But the segments were impossible to see, hidden somewhere behind a far-off ridge. Even if they'd been visible, they would have seemed impossibly small.

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

"We call it Mexus," says Cruz. Destined for the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of Architecture - the design world's premier showcase for new ideas, opening this May - Cruz and Forman's Mexus project uses maps, renderings and diagrams to send a pointed political message. As Forman explains, "We've been interested in documenting the flows, invisible and visible, that move back and forth across the border." The duo's exhibition includes ideas both grounded and improbable for turning the region into an integral whole - culturally, economically and ecologically - with a special focus on the area's combined watershed. Mexus, says Cruz, is "a region that contains all the stuff that walls cannot stop."

The pair - one an architect, the other a political scientist - have spent years looking at the border, mostly through conceptual inquiries like Mexus but also through more tangible projects. For instance, their firm has designed Cross-Border Community Stations - outposts developed in partnership with UCSD to foster grass-roots social research - that are underway in San Diego and Tijuana. Together, these projects - from far-sighted to practical - suggest how architecture can provide a counterweight to our current wall-crazed, deportation-frenzied moment by blurring, rather than accentuating, the divisions between the United States and Mexico.

University of California at San Diego's Cross-Border Community Station is expected to break ground.

But since the 2016 election, architectural offices on both sides of the border - of all sizes and dispensations, from high-flown academic to high-end commercial - have found themselves in a strange new climate. "We were all thinking that we were leaving a moment of invisibility and moving into a moment of inclusion," says Henry Munoz. "Instead we became a target." The principal (not an architect himself, but CEO) of San Antonio-based design firm Munoz and Co., he also happens to be the finance chairman of the Democratic National Committee and a lifelong activist for Latino and Mexican American causes. Speaking of his personal outlook, he refers to the concept of the "transnational imaginary": not just an identity, but a kind of spatialized mental paradigm, one characterized by "sharing, fluidity, mixed families," and only partially divided by a border that "we didn't cross, but that crossed us."

As applied to architecture, the concept of transnationality can take many forms. In 2005, for instance, Munoz and Co.'s educational complex for the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley featured a glass-enclosed elevator shaft whose etched panels sport traditional Mexican dichos, or proverbs, in both English and Spanish, the two languages mixing increasingly as the elevator ascends. Today, one of Munoz's ongoing projects is a master plan for Brownsville, Texas, a scheme whose primary objective is to transform the city's downtown into a thriving mixed-use district - counteracting the encroachments of border wall construction, which has continued to slice away at the physical fabric of the area.

For contemporary global architects - studios in multiple countries, plane tickets always at the ready - transnationality comes fairly naturally, and ideas continue to flow freely across the border despite the bellicose rhetoric surrounding the immigration debate. This is especially true for an architect like Alfonso Medina, who was born in Texas to Mexican parents and raised primarily in Tijuana. Today he keeps one branch of his firm, T38 Studio, in the famed border town and another in New York City.

Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman's Mexus project uses maps, renderings to send a pointed political message.

Medina is hardly the only architect whose background transcends the U.S.-Mexico border. Speaking to me from a classic Mexico City traffic jam, architect Frida Escobedo explained her own split architectural identity, working in her native Mexico while teaching in the United States and taking on commissions around the world. "I find it easier to understand some of the ideas about architecture in the U.S. than in Mexico," she says. Her sojourns abroad have allowed her to meet a network of friends and teachers, and led to both small commissions - a pair of subdued boutiques in Florida for cosmetics maker Aesop - and larger ones, most notably the 2018 Serpentine Pavilion, the annual temporary structure in London's Hyde Park that has seen previous iterations from the likes of Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid. Debuting this June, Escobedo's pavilion includes a water feature and a surrounding lattice wall that recalls, in its quiet intimacy, something of old Mexican courtyard houses.

There may be no better example of the ongoing cross-border pollination in architecture than the fact that NASA - arguably the last word in flag-waving all-American-ness - has hired TEN Arquitectos to design a 60,000-square-foot complex for the Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. Founded in Mexico City in 1986, the architecture firm operates a major satellite in New York City. In its NASA project, set to break ground this summer, style definitely takes a back seat; the buildings are a simple ensemble of glass boxes, their reserve in keeping with the client's scientific agenda. But then, TEN Arquitectos, whose workload also includes the new Mexican Museum in San Francisco, has always specialized in a sober-minded functionalism.

Architect Frida Escobedo will debut her 2018 Serpentine Pavilion in June.

Yet another architect working at the intersection of U.S. and Mexican culture is Fernando Romero, whose Mexico City-based firm also keeps a shop in Manhattan. While working on the Mexican capital's new airport, Romero has simultaneously been commissioned by Elon Musk to produce a speculative design for the investor's ambitious Hyperloop One high-speed transportation system. In Romero's proposal, the network would create a transnational link between the major cities of northern Mexico and the U.S. side of the border - not a likely prospect for the immediate future, but one that the architect considers well within the realm of the possible.

"We are convinced Mexico is the best partner the U.S. has," Romero says. He's confident that this view will prevail among Americans who are "informed, sensible and have a wider understanding of the realities."

Indeed, Romero - like Cruz and Forman - has also developed a scheme for bridging the physical boundary between the two countries: a visionary "Border City," half in Mexico and half in the United States, which would operate as a seamless whole. Romero has been invested in the subject for a long time. In 2008, he produced a book called "Hyperborder," a sweeping data-packed survey of the whole regional condition. "Border City" appeared eight years later at the London Design Biennale, whose theme was "Utopia by Design." No less far-fetched than the Hyperloop, the project nonetheless shows that despite the challenging times, designers' sense of global mission is still intact, and that the fraught love affair between the United States and Mexico - so often expressed in architecture - has a little life in it yet.

T38 Studio's Arboleda apartment complex caters both to the Mexican creative class and to San Diegans.

We walked into the building's gracious common area, cantilevered dramatically over a hillside with a lush semitropical garden below. Out the window was a dramatic view: miles of houses (most of them, it should be said, considerably less commodious) covering every hillside and lining the river that cut through Cruz and Forman's wall map as a blue strip of masking tape.

To the northeast, just on the far side of the border, was a building site for prototype segments for the proposed border wall, the permanent, 30-foot-high concrete barrier that may one day run between Mexico and the United States. But the segments were impossible to see, hidden somewhere behind a far-off ridge. Even if they'd been visible, they would have seemed impossibly small.

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world