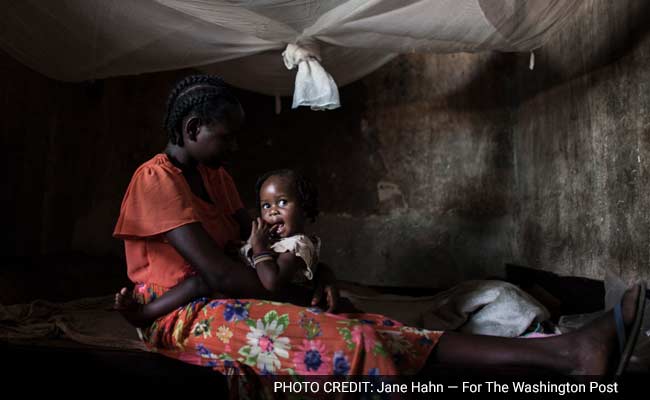

Rosine Mengue, 18, holds her 1-year-old son.

BANGUI, Central African Republic:

The neighborhood is a patchwork of low-slung buildings scorched and looted at the height of the civil war, a place where the United Nations was supposed to come to the rescue. But in a number of homes, women and girls are raising babies they say are the children of UN troops who abused or exploited them.

"Peacekeeper babies," the United Nations calls such infants.

"A horrible thing," says an elfin 14-year-old girl, who describes how a Burundian soldier dragged her into his barracks and raped her, leaving her pregnant with the baby boy she now cradles uncomfortably.

The allegations come amid one of the biggest scandals to plague the United Nations in years. Since the UN peacekeeping mission here began in 2014, its employees have been formally accused of sexually abusing or exploiting 42 local civilians, most of them underage girls.

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has called sexual abuse by peacekeepers "a cancer in our system." In August, the top UN official here was fired for failing to take enough action on abuse cases. Nearly 1,000 troops whose units have been tied to abuses have been expelled, or will be soon. Among them is the entire contingent from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But the victims appear to be more numerous than the United Nations has acknowledged so far. In a corner of the capital city known as Castors, near the UN headquarters in the country, The Washington Post interviewed seven women and girls who described contact with peacekeepers that violated UN regulations against sexual exploitation and abuse. Five of them said they exchanged sex for food or money - sometimes as little as $4 - while their country was rocked by civil war and families were going hungry. Two had reported their cases to the United Nations.

Five of the seven interviewed by The Post said they had borne the children of their abusers. The 14-year-old mother said she was raped, but the United Nations recorded her case as involving "transactional" sex, in which acts are exchanged for money or food.

"Sometimes when I'm alone with my baby, I think about killing him," the teen said, holding the little boy. "He reminds me of the man who raped me."

The Washington Post does not usually identify minors who are victims of sexual abuse or exploitation.

The accounts by the women and girls could not be independently verified. But their stories echoed other accounts of abuse in the Central African Republic collected by independent groups and the United Nations.

The UN system responsible for handling and prosecuting such cases has been widely criticized as dysfunctional, even after scandals involving peacekeepers in other parts of the world. Only one criminal charge has been filed in relation to any of the 42 cases of sexual abuse or exploitation that have been officially registered in the Central African Republic, according to UN officials.

UN officials did file a report on the 14-year-old mother's allegations, and a UN spokeswoman, Ismini Palla, said the organization was "monitoring the case of the girl closely." But nine months after the girl reported the alleged rape, investigators have not reported any results.

UN officials did file a report on the 14-year-old mother's allegations, and a UN spokeswoman, Ismini Palla, said the organization was "monitoring the case of the girl closely." But nine months after the girl reported the alleged rape, investigators have not reported any results.

The sexual abuse scandal is the latest horrific development in a war already marked by extreme brutality. The conflict began in late 2013 when mostly Muslim rebels overthrew the government in this Christian-majority country, setting off a cycle of revenge killings that in Bangui fell largely along religious lines. About 6,000 people have been killed. The UN mission, which includes troops from 46 countries and is known as MINUSCA, was established to provide security and protect civilians.

Numerous allegations have emerged in recent months of peacekeeper abuse of vulnerable residents. Human Rights Watch issued a report this month documenting the cases of eight women and girls allegedly raped or sexually exploited by UN peacekeepers in late 2015 in the central city of Bambari. Amnesty International said last August that it had obtained evidence of a UN peacekeeper's rape of a 12-year-old girl in the capital.

UN officials recognize that they are grappling with a serious breakdown in their peacekeeping forces. This month, they said they were investigating the cases of four girls who were allegedly exploited or abused at a camp for internally displaced persons in central Ouaka prefecture. In January, they said that at least four peacekeepers had allegedly paid girls as little as 50 cents for sex at a camp in Bangui.

"We're going to be flooded by paternity claims," Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, the newly appointed head of the UN mission, said in an interview.

It is not the first deployment in which UN forces have been accused of sexual abuse. In Bosnia in the 1990s, peacekeepers were accused of soliciting sex from women who had been trafficked and virtually enslaved in local brothels. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the early 2000s, more than 150 allegations of abuse and exploitation were registered against peacekeepers, and UN investigators found that many of the alleged victims were orphans.

UN missions in Kosovo, Haiti, Liberia and other places also have been tarnished by such allegations.

The United Nations has conducted internal investigations and revamped training programs. But the complaints continue to roll in.

Perhaps no mission in recent UN history has been as quickly tainted by abuse allegations as the one in the Central African Republic. The 12,000-member operation was established in 2014 and is expected to cost $814 million this year. The first cluster of sexual abuse cases appeared within months.

Even before the UN mission officially began, French troops were accused of sexually abusing a number of local children. In a report issued last year, a UN-appointed review panel sharply criticized UN officials in the Central African Republic as failing to take action or report the cases after uncovering them.

"The welfare of the victims and the accountability of the perpetrators appeared to be an afterthought, if considered at all," the report said.

UN bases in the Central African Republic are now plastered with posters that list the rules that troops are already supposed to know.

"Sex with anyone under the age of 18 is prohibited."

"Exchanging money, goods or employment for sex is prohibited."

"Zero tolerance for sexual exploitation."

But the Castors neighborhood is a shocking illustration of how brazen the peacekeepers became. Residents say that troops skulked around the neighborhood looking for girls during the day and sneaked out at night to meet them in rented rooms or abandoned houses, or to take them into the barracks. Moroccan troops broke holes in the perimeter wall of their bases, witnesses said, so that they could leave undetected.

"There are so many girls here who slept with [peacekeepers]," said Thierry Karpandgei, a resident. "You can see their babies all over here."

Most of the alleged cases of abuse and exploitation occurred at the peak of the conflict, in 2014 and 2015, when the fighting pushed residents to the edge of survival.

"There was no way to get food or money at the time, and they promised to help us if we slept with them," said Rosine Mengue, who explained that she received the equivalent of $4 in each of two encounters with a peacekeeper. She was 16 at the time. She spent the money on cassava leaves, which fed her family for two days. Mengue, who is now 18, told The Washington Post it could use her full name.

Like the rest of the women, Mengue never heard from the man after she became pregnant, she said. He went back to Morocco. She dropped out of school and is raising her son in her family's home, surrounded by charred palm trees and the ruins of half-destroyed buildings.

"We don't have enough food for everyone," her mother said.

Most of the women interviewed by The Post said they did not report their cases to the United Nations because they felt ashamed and did not think the organization would be able to help them. One of the women did approach the United Nations seeking financial assistance for her baby after his father returned to the Congo Republic. But UN officials say she did not specify that she had received money from the peacekeeper - as she later told The Post - so the case was not recorded as involving exploitation. Such an act would have violated UN rules for peacekeepers on sexual relationships.

Castors is along the road from the sprawling UN headquarters, where Onanga-Anyanga, 55, a veteran UN official from Gabon, is scrambling to solve the problem. In an interview this month, he sat in front of a sheet of paper that said in bold print: "Talking points - Sexual Exploitation and Abuse." When he looked up, he spoke angrily.

"We inherited troops that we cannot call troops. I realized that what was sent here was trash," he said.

There are a range of explanations for the rampant abuse, including the poor training and discipline of many battalions, which are dispatched here for years-long rotations, said UN officials and analysts. Some troops were sent in 2013 as part of an African Union operation and then were "re-hatted" as UN peacekeepers with little or no additional instruction.

"We can't just put a blue helmet on them and assume their mind-set will change overnight," Onanga-Anyanga said.

UN officials here have tried to encourage the reporting of sexual abuse by setting up a hotline for victims and buying radio ads in which they are encouraged to come forward. Victims of abuse whose cases are documented are eligible for medical and psychological help and possibly other recompense. But many women are still unaware of how to register complaints.

Even as the United Nations has tried to improve training on sexual abuse, there have been mistakes. Many of the new lessons, for example, are taught only in English and French, and some troops lack fluency in either language, said one UN official, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to comment on the issue.

Perhaps most problematic is that the United Nations leaves the adjudication of sexual abuse allegations to the troops' countries of origin. But those nations' investigations are often weak, UN officials said. That has contributed to a sense of impunity, according to UN officials and outside experts.

For peacekeepers in the Central African Republic, "the message is clear: You can rape or abuse women and girls and you can get away with it," said Lewis Mudge, an Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. "Until troop-contributing countries bring peacekeepers accused of these crimes to justice, we can expect more of these cases in the future."

The 14-year-old mother still watches the troops drive near her faded-yellow home, where broken beer bottles are glued on top of the outside wall to keep trespassers out. She and other residents said they first saw the peacekeepers as a sign of security, proof that the world hadn't forgotten about them.

But when the soldiers began arriving in 2014, there was still a massive food shortage. Some peacekeepers recognized their leverage over a city of starving women and girls.

But when the soldiers began arriving in 2014, there was still a massive food shortage. Some peacekeepers recognized their leverage over a city of starving women and girls.

Two teenage girls recalled approaching a base of Moroccan peacekeepers to beg for food. Neither had ever had sex, they said in a recent interview, but they agreed to sleep with the soldiers after the men suggested they would give the girls water, food and money. The older girl, then 16, said she met one man in a vacant house. The younger girl, then 15, said she met another soldier next to a base. Both girls said they regretted what they had done almost immediately.

"You just feel used," said the younger girl.

The 14-year-old said that when she went to a UN base last year to ask for food, a Burundian soldier gently beckoned to her from his barracks, calling, "Come here."

Then, she said, he pulled her into a room full of empty beds. He ripped off her clothes.

The teenager and her aunt said that three months later, they told two UN employees what had happened. The pregnant girl was then taken to a hospital run by Doctors Without Borders, the medical group said. But aid workers who followed the girl's case over the next few weeks said they were dismayed at how little help she received from the United Nations.

"There was absolutely no immediate or concrete measure of assistance available to this girl," said Ondine Ripka, an international legal adviser with Doctors Without Borders.

A UNICEF spokesman, John Budd, said the organization does not comment on aid provided to individuals. The 14-year-old mother said she had not received any psychological counseling or financial assistance.

In a 2005 internal report recognizing the problem of "peacekeeper babies," UN officials wrote that "there is a need to try to ensure that fathers, who can be identified, perhaps through blood or DNA testing, bear some financial responsibility for their actions."

But it is often difficult to identify offenders who have returned to their home countries, UN officials say. Even if victims know the names of their abusers, armies in many nations have proved uncooperative in pursuing DNA tests, UN officials say.

The teenage mother's case was referred to the Burundian military, which appointed an investigator, according to UN officials, but no results have so far been reported. That country has been consumed in civil strife in recent months, and experts said it was unlikely the military would follow through on an investigation.

That leaves girls like the 14-year-oldto raise their babies on almost nothing, as the war rages on. Earlier this month, she sat outside her home, five rooms where more than 20 relatives sleep. Nearby, a man sold liquor from a plastic table. A white U.N. surveillance blimp flew overhead. Two hundred yards away, a group of Burundian troops was on patrol.

The teenager handed her baby to her mother, who looked at the ground. She fears that her daughter has been ruined by the abuse.

"If someone destroys what you love, what do you do?" the mother said.

© 2016 The Washington Post

"Peacekeeper babies," the United Nations calls such infants.

"A horrible thing," says an elfin 14-year-old girl, who describes how a Burundian soldier dragged her into his barracks and raped her, leaving her pregnant with the baby boy she now cradles uncomfortably.

The allegations come amid one of the biggest scandals to plague the United Nations in years. Since the UN peacekeeping mission here began in 2014, its employees have been formally accused of sexually abusing or exploiting 42 local civilians, most of them underage girls.

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has called sexual abuse by peacekeepers "a cancer in our system." In August, the top UN official here was fired for failing to take enough action on abuse cases. Nearly 1,000 troops whose units have been tied to abuses have been expelled, or will be soon. Among them is the entire contingent from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But the victims appear to be more numerous than the United Nations has acknowledged so far. In a corner of the capital city known as Castors, near the UN headquarters in the country, The Washington Post interviewed seven women and girls who described contact with peacekeepers that violated UN regulations against sexual exploitation and abuse. Five of them said they exchanged sex for food or money - sometimes as little as $4 - while their country was rocked by civil war and families were going hungry. Two had reported their cases to the United Nations.

Five of the seven interviewed by The Post said they had borne the children of their abusers. The 14-year-old mother said she was raped, but the United Nations recorded her case as involving "transactional" sex, in which acts are exchanged for money or food.

"Sometimes when I'm alone with my baby, I think about killing him," the teen said, holding the little boy. "He reminds me of the man who raped me."

The Washington Post does not usually identify minors who are victims of sexual abuse or exploitation.

The accounts by the women and girls could not be independently verified. But their stories echoed other accounts of abuse in the Central African Republic collected by independent groups and the United Nations.

The UN system responsible for handling and prosecuting such cases has been widely criticized as dysfunctional, even after scandals involving peacekeepers in other parts of the world. Only one criminal charge has been filed in relation to any of the 42 cases of sexual abuse or exploitation that have been officially registered in the Central African Republic, according to UN officials.

A young woman sits at home with her 1-year-old daughter. She says that when she was 17, a U.N. peacekeeper from the Republic of the Congo coerced her into having sex for money and food, leaving her pregnant.

The sexual abuse scandal is the latest horrific development in a war already marked by extreme brutality. The conflict began in late 2013 when mostly Muslim rebels overthrew the government in this Christian-majority country, setting off a cycle of revenge killings that in Bangui fell largely along religious lines. About 6,000 people have been killed. The UN mission, which includes troops from 46 countries and is known as MINUSCA, was established to provide security and protect civilians.

Numerous allegations have emerged in recent months of peacekeeper abuse of vulnerable residents. Human Rights Watch issued a report this month documenting the cases of eight women and girls allegedly raped or sexually exploited by UN peacekeepers in late 2015 in the central city of Bambari. Amnesty International said last August that it had obtained evidence of a UN peacekeeper's rape of a 12-year-old girl in the capital.

UN officials recognize that they are grappling with a serious breakdown in their peacekeeping forces. This month, they said they were investigating the cases of four girls who were allegedly exploited or abused at a camp for internally displaced persons in central Ouaka prefecture. In January, they said that at least four peacekeepers had allegedly paid girls as little as 50 cents for sex at a camp in Bangui.

"We're going to be flooded by paternity claims," Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, the newly appointed head of the UN mission, said in an interview.

It is not the first deployment in which UN forces have been accused of sexual abuse. In Bosnia in the 1990s, peacekeepers were accused of soliciting sex from women who had been trafficked and virtually enslaved in local brothels. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the early 2000s, more than 150 allegations of abuse and exploitation were registered against peacekeepers, and UN investigators found that many of the alleged victims were orphans.

UN missions in Kosovo, Haiti, Liberia and other places also have been tarnished by such allegations.

The United Nations has conducted internal investigations and revamped training programs. But the complaints continue to roll in.

Perhaps no mission in recent UN history has been as quickly tainted by abuse allegations as the one in the Central African Republic. The 12,000-member operation was established in 2014 and is expected to cost $814 million this year. The first cluster of sexual abuse cases appeared within months.

Even before the UN mission officially began, French troops were accused of sexually abusing a number of local children. In a report issued last year, a UN-appointed review panel sharply criticized UN officials in the Central African Republic as failing to take action or report the cases after uncovering them.

"The welfare of the victims and the accountability of the perpetrators appeared to be an afterthought, if considered at all," the report said.

UN bases in the Central African Republic are now plastered with posters that list the rules that troops are already supposed to know.

"Sex with anyone under the age of 18 is prohibited."

"Exchanging money, goods or employment for sex is prohibited."

"Zero tolerance for sexual exploitation."

But the Castors neighborhood is a shocking illustration of how brazen the peacekeepers became. Residents say that troops skulked around the neighborhood looking for girls during the day and sneaked out at night to meet them in rented rooms or abandoned houses, or to take them into the barracks. Moroccan troops broke holes in the perimeter wall of their bases, witnesses said, so that they could leave undetected.

"There are so many girls here who slept with [peacekeepers]," said Thierry Karpandgei, a resident. "You can see their babies all over here."

Most of the alleged cases of abuse and exploitation occurred at the peak of the conflict, in 2014 and 2015, when the fighting pushed residents to the edge of survival.

"There was no way to get food or money at the time, and they promised to help us if we slept with them," said Rosine Mengue, who explained that she received the equivalent of $4 in each of two encounters with a peacekeeper. She was 16 at the time. She spent the money on cassava leaves, which fed her family for two days. Mengue, who is now 18, told The Washington Post it could use her full name.

Like the rest of the women, Mengue never heard from the man after she became pregnant, she said. He went back to Morocco. She dropped out of school and is raising her son in her family's home, surrounded by charred palm trees and the ruins of half-destroyed buildings.

"We don't have enough food for everyone," her mother said.

Most of the women interviewed by The Post said they did not report their cases to the United Nations because they felt ashamed and did not think the organization would be able to help them. One of the women did approach the United Nations seeking financial assistance for her baby after his father returned to the Congo Republic. But UN officials say she did not specify that she had received money from the peacekeeper - as she later told The Post - so the case was not recorded as involving exploitation. Such an act would have violated UN rules for peacekeepers on sexual relationships.

Castors is along the road from the sprawling UN headquarters, where Onanga-Anyanga, 55, a veteran UN official from Gabon, is scrambling to solve the problem. In an interview this month, he sat in front of a sheet of paper that said in bold print: "Talking points - Sexual Exploitation and Abuse." When he looked up, he spoke angrily.

"We inherited troops that we cannot call troops. I realized that what was sent here was trash," he said.

There are a range of explanations for the rampant abuse, including the poor training and discipline of many battalions, which are dispatched here for years-long rotations, said UN officials and analysts. Some troops were sent in 2013 as part of an African Union operation and then were "re-hatted" as UN peacekeepers with little or no additional instruction.

"We can't just put a blue helmet on them and assume their mind-set will change overnight," Onanga-Anyanga said.

UN officials here have tried to encourage the reporting of sexual abuse by setting up a hotline for victims and buying radio ads in which they are encouraged to come forward. Victims of abuse whose cases are documented are eligible for medical and psychological help and possibly other recompense. But many women are still unaware of how to register complaints.

Even as the United Nations has tried to improve training on sexual abuse, there have been mistakes. Many of the new lessons, for example, are taught only in English and French, and some troops lack fluency in either language, said one UN official, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to comment on the issue.

Perhaps most problematic is that the United Nations leaves the adjudication of sexual abuse allegations to the troops' countries of origin. But those nations' investigations are often weak, UN officials said. That has contributed to a sense of impunity, according to UN officials and outside experts.

For peacekeepers in the Central African Republic, "the message is clear: You can rape or abuse women and girls and you can get away with it," said Lewis Mudge, an Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. "Until troop-contributing countries bring peacekeepers accused of these crimes to justice, we can expect more of these cases in the future."

The 14-year-old mother still watches the troops drive near her faded-yellow home, where broken beer bottles are glued on top of the outside wall to keep trespassers out. She and other residents said they first saw the peacekeepers as a sign of security, proof that the world hadn't forgotten about them.

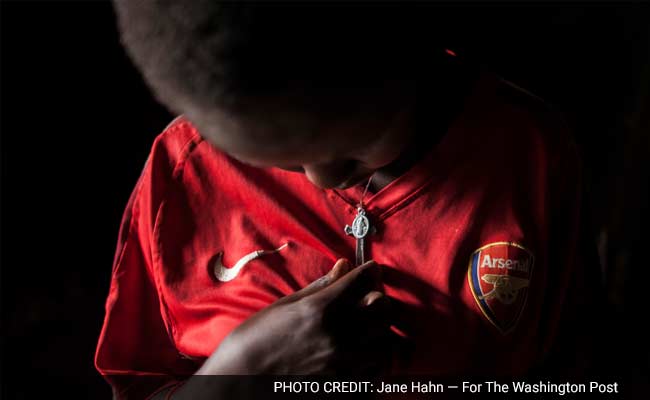

A 14-year-old girl says that last year she was raped by a peacekeeper from Burundi and became pregnant.

Two teenage girls recalled approaching a base of Moroccan peacekeepers to beg for food. Neither had ever had sex, they said in a recent interview, but they agreed to sleep with the soldiers after the men suggested they would give the girls water, food and money. The older girl, then 16, said she met one man in a vacant house. The younger girl, then 15, said she met another soldier next to a base. Both girls said they regretted what they had done almost immediately.

"You just feel used," said the younger girl.

The 14-year-old said that when she went to a UN base last year to ask for food, a Burundian soldier gently beckoned to her from his barracks, calling, "Come here."

Then, she said, he pulled her into a room full of empty beds. He ripped off her clothes.

The teenager and her aunt said that three months later, they told two UN employees what had happened. The pregnant girl was then taken to a hospital run by Doctors Without Borders, the medical group said. But aid workers who followed the girl's case over the next few weeks said they were dismayed at how little help she received from the United Nations.

"There was absolutely no immediate or concrete measure of assistance available to this girl," said Ondine Ripka, an international legal adviser with Doctors Without Borders.

A UNICEF spokesman, John Budd, said the organization does not comment on aid provided to individuals. The 14-year-old mother said she had not received any psychological counseling or financial assistance.

In a 2005 internal report recognizing the problem of "peacekeeper babies," UN officials wrote that "there is a need to try to ensure that fathers, who can be identified, perhaps through blood or DNA testing, bear some financial responsibility for their actions."

But it is often difficult to identify offenders who have returned to their home countries, UN officials say. Even if victims know the names of their abusers, armies in many nations have proved uncooperative in pursuing DNA tests, UN officials say.

The teenage mother's case was referred to the Burundian military, which appointed an investigator, according to UN officials, but no results have so far been reported. That country has been consumed in civil strife in recent months, and experts said it was unlikely the military would follow through on an investigation.

That leaves girls like the 14-year-oldto raise their babies on almost nothing, as the war rages on. Earlier this month, she sat outside her home, five rooms where more than 20 relatives sleep. Nearby, a man sold liquor from a plastic table. A white U.N. surveillance blimp flew overhead. Two hundred yards away, a group of Burundian troops was on patrol.

The teenager handed her baby to her mother, who looked at the ground. She fears that her daughter has been ruined by the abuse.

"If someone destroys what you love, what do you do?" the mother said.

© 2016 The Washington Post

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world