New York:

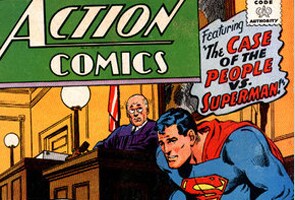

The case of "The People vs Superman" is not found in the hornbooks that are scoured by the nation's law students. But if they had been youngsters in 1967, when Action Comics No 359 first came out, they might have been amazed to see the Man of Steel in an unusual situation. Instead of zooming through the sky or confronting talkative archvillains, he is in a courtroom, sitting in the witness chair. A little girl is standing in front of the Man of Steel, pointing at him.

"That's him!" she shouts. "He's the man who killed my Daddy!"

If you missed that scene -- or the one of the Hulk smashing up a courtroom just before sentencing in "The Incredible Hulk vs. Everybody" from 1972 -- you can see them at Yale University, in the Lillian Goldman Law Library's rare book exhibition gallery.

The show, "Superheroes in Court! Lawyers, Law and Comic Books," provides images of superheroes in the dock, comic books about lawyers and examples of legal disputes and Congressional inquiries involving caped crusaders.

You might think that a rare books librarian at a prestigious institution would be displaying something like Magna Carta. Or maybe the original publication of the opinion in Hawkins v McGee, the 1929 contracts case filed by a surgery patient whose botched skin graft left him with a hairy hand. (The case is often taught in contracts classes and was made famous in "The Paper Chase.") And of course the collection does have its medieval tomes and papers of esteemed jurists -- it is, after all, considered to be one of the finest collections of rare law books in the world.

But the library also has its playful side, and has archived, for example, an assortment of bobblehead dolls representing members of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Mike Widener, the law library's rare book librarian, said that comics were a natural fit with the institution's interest in "law and popular culture." And so he came up with the idea of an exhibition on the law and comics.

He asked Mark S Zaid, a Washington lawyer who collects and sells comics through his Web site, esquirecomics.com, to be guest curator for the exhibition. Mr Zaid said he selected comics and memorabilia that show "the heavy influence of law, and lawyers, in creating one of the greatest pop culture industries the world has ever seen."

The medium serves as a guide to what was going on in society at the time, he said: "Comics are very much a reflection of pop culture." The law has long been a part of that, whether it's Perry Mason grilling a witness or Denny Crane blustering.

In the exhibition, many of the images have the power to delight, especially for those who collected comics in their youth. If your day job happens to be anything like mine -- I'm the national legal correspondent for this newspaper -- you will certainly notice that the comic book creators' knowledge of law had a few gaps. For starters, the little girl in that Superman cover would have been seated in the witness chair, if in fact taking sworn testimony from a minor in open court was allowed in the Metropolis jurisdiction, and Superman would have been elsewhere in the courtroom. But you probably won't mind that the creators sacrificed a bit of reality for drama, which is also why, you know, the main character can fly.

There are comics, as well, whose characters are lawyers, like Mr District Attorney, a comic drawn from a radio show, and The Defenders, based on a 1960s elevision program of the same name. (There is no sign, alas, of Matt Murdock, the lawyer alter ego of Daredevil, the Marvel Comics superhero.) The exhibition also includes "Wolff & Byrd: Counselors of the Macabre." The strip first appeared in The Brooklyn Paper in the late '70s and later appeared in The National Law Journal. It chronicles the adventures of two lawyers in Brooklyn who deal with supernatural clients, including vampires who want legal protection against a certain teenage slayer, and issues like the property damage claims after a Hulk-like superhero goes berserk.

The show, almost all of which comes from Mr Zaid's personal collection, also contains items from significant legal matters involving comic books -- for example, a telegram related to a copyright infringement suit concerning a character, "Wonder Man," who was an awful lot like Superman. Wonder Man might have been faster than a locomotive, but he was no match for a speeding gavel: he appeared in only one issue, in 1939, before the lawsuit by the company that would later be known as DC Comics killed him off. The artist who was a creator of Superman, Jerome Siegel, known as Jerry, and his heirs would also engage in rounds of litigation against DC over the true ownership of Superman and Superboy; the Yale exhibition contains correspondence from that fight.

And, as with all works of literature, the comics have spawned First Amendment disputes, in this case pitting free speech against the dangers of harming young psyches with depictions of things like crime and horror. The show displays a report to the United States Senate, "Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency," from 1955, and an American Civil Liberties Union report from the same year, "Censorship of Comic Books."

The exhibition runs until December, crimefighters.

Mr Zaid, who represents spies in his legal practice, said he had long found himself drawn to comics about lawyers and spies. He started Esquire Comics in 2004, reviving his childhood hobby and making it pay.

"Tons of lawyers are collectors," he said. Like Mr Zaid, they might have read and collected comics as children but let the hobby lapse as they made their way through college and started their working lives. "They come back to it once they settle into a career and a family and they have disposable cash," he said -- though he added that many are "closet collectors" who ask, "Can I be a professional and still play with comic books?"

His answer, of course, is yes. Still, is it possible that a display of comic books could be seen as being somehow beneath the dignity of an institution like Yale Law School? Mr Zaid scoffed at the idea, noting that some of the comics on display in the exhibition are worth $25,000.

"I don't think anything worth $25,000 is beneath the dignity of Yale," he said.

"That's him!" she shouts. "He's the man who killed my Daddy!"

If you missed that scene -- or the one of the Hulk smashing up a courtroom just before sentencing in "The Incredible Hulk vs. Everybody" from 1972 -- you can see them at Yale University, in the Lillian Goldman Law Library's rare book exhibition gallery.

The show, "Superheroes in Court! Lawyers, Law and Comic Books," provides images of superheroes in the dock, comic books about lawyers and examples of legal disputes and Congressional inquiries involving caped crusaders.

You might think that a rare books librarian at a prestigious institution would be displaying something like Magna Carta. Or maybe the original publication of the opinion in Hawkins v McGee, the 1929 contracts case filed by a surgery patient whose botched skin graft left him with a hairy hand. (The case is often taught in contracts classes and was made famous in "The Paper Chase.") And of course the collection does have its medieval tomes and papers of esteemed jurists -- it is, after all, considered to be one of the finest collections of rare law books in the world.

But the library also has its playful side, and has archived, for example, an assortment of bobblehead dolls representing members of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Mike Widener, the law library's rare book librarian, said that comics were a natural fit with the institution's interest in "law and popular culture." And so he came up with the idea of an exhibition on the law and comics.

He asked Mark S Zaid, a Washington lawyer who collects and sells comics through his Web site, esquirecomics.com, to be guest curator for the exhibition. Mr Zaid said he selected comics and memorabilia that show "the heavy influence of law, and lawyers, in creating one of the greatest pop culture industries the world has ever seen."

The medium serves as a guide to what was going on in society at the time, he said: "Comics are very much a reflection of pop culture." The law has long been a part of that, whether it's Perry Mason grilling a witness or Denny Crane blustering.

In the exhibition, many of the images have the power to delight, especially for those who collected comics in their youth. If your day job happens to be anything like mine -- I'm the national legal correspondent for this newspaper -- you will certainly notice that the comic book creators' knowledge of law had a few gaps. For starters, the little girl in that Superman cover would have been seated in the witness chair, if in fact taking sworn testimony from a minor in open court was allowed in the Metropolis jurisdiction, and Superman would have been elsewhere in the courtroom. But you probably won't mind that the creators sacrificed a bit of reality for drama, which is also why, you know, the main character can fly.

There are comics, as well, whose characters are lawyers, like Mr District Attorney, a comic drawn from a radio show, and The Defenders, based on a 1960s elevision program of the same name. (There is no sign, alas, of Matt Murdock, the lawyer alter ego of Daredevil, the Marvel Comics superhero.) The exhibition also includes "Wolff & Byrd: Counselors of the Macabre." The strip first appeared in The Brooklyn Paper in the late '70s and later appeared in The National Law Journal. It chronicles the adventures of two lawyers in Brooklyn who deal with supernatural clients, including vampires who want legal protection against a certain teenage slayer, and issues like the property damage claims after a Hulk-like superhero goes berserk.

The show, almost all of which comes from Mr Zaid's personal collection, also contains items from significant legal matters involving comic books -- for example, a telegram related to a copyright infringement suit concerning a character, "Wonder Man," who was an awful lot like Superman. Wonder Man might have been faster than a locomotive, but he was no match for a speeding gavel: he appeared in only one issue, in 1939, before the lawsuit by the company that would later be known as DC Comics killed him off. The artist who was a creator of Superman, Jerome Siegel, known as Jerry, and his heirs would also engage in rounds of litigation against DC over the true ownership of Superman and Superboy; the Yale exhibition contains correspondence from that fight.

And, as with all works of literature, the comics have spawned First Amendment disputes, in this case pitting free speech against the dangers of harming young psyches with depictions of things like crime and horror. The show displays a report to the United States Senate, "Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency," from 1955, and an American Civil Liberties Union report from the same year, "Censorship of Comic Books."

The exhibition runs until December, crimefighters.

Mr Zaid, who represents spies in his legal practice, said he had long found himself drawn to comics about lawyers and spies. He started Esquire Comics in 2004, reviving his childhood hobby and making it pay.

"Tons of lawyers are collectors," he said. Like Mr Zaid, they might have read and collected comics as children but let the hobby lapse as they made their way through college and started their working lives. "They come back to it once they settle into a career and a family and they have disposable cash," he said -- though he added that many are "closet collectors" who ask, "Can I be a professional and still play with comic books?"

His answer, of course, is yes. Still, is it possible that a display of comic books could be seen as being somehow beneath the dignity of an institution like Yale Law School? Mr Zaid scoffed at the idea, noting that some of the comics on display in the exhibition are worth $25,000.

"I don't think anything worth $25,000 is beneath the dignity of Yale," he said.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world