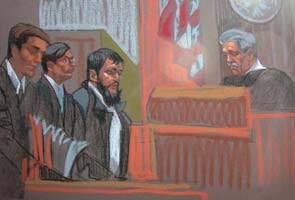

Courtroom sketch shows Bosnian-born Adis Medunjanin (AFP)

New York:

A taxi driver, doorman and former coffee cart vendor, the three typical Americans went to school, prayed and played basketball together. Then they tried to go to war together - against America.

A trial underway in New York against a man accused in a 2009 suicide bomb attempt is exploring what the government calls one of the most serious terrorist plots on US soil since September 11, 2001.

But the case against Adis Medunjanin, 28, has also bared the wider world of homegrown US terrorism, a world of fanatical, bumbling Al Qaeda wannabes, and a law enforcement machine so tight that those jihad dreams rarely get put into action.

Ninety six attempted terrorist plots have been hatched on US soil since 9/11, experts say. Of these, only 11 can "generously" be classified as feasible, said Brian Jenkins, at the Rand Corporation.

"American jihadists bark, brag, sniff at edges, but are skittish and more closely resemble stray dogs than lone wolves," Mr Jenkins said.

The unprofessionalism, however, is also what makes them so hard to identify, resulting in a "more diffused threat," Mr Jenkins added.

Medunjanin and his two Flushing High School friends fitted that description perfectly.

Almost stereotypical working class New Yorkers, they came from immigrant families, were sports mad, strived to get an education, and worked classic entry-level jobs.

Medunjanin, now facing life in prison if convicted on all counts, came to New York as a child when his Muslim family fled Bosnia during the war against the Serbs in the early 1990s. Pudgy, but sporty, intelligent and said to possess natural leadership skills, he was on a good trajectory.

On 9/11, he was 17. "He was appalled by what he witnessed, as everyone else was," his defence attorney Robert Gottlieb said at the trial, which started on Monday.

But amid shockwaves from the US invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, the increasingly devout Medunjanin became angry.

At home, "he saw and suffered what can only be described as a wave of anti-Muslim hatred," Mr Gottlieb said. On television and on the Internet, he "heard about the drone attacks, the unmanned planes that drop bombs in Afghanistan.... He heard about the atrocities."

Finally, "he felt the need to come to the aid of his religion." By 2008, this mild-mannered Manhattan doorman was on a plane to Pakistan to join the Taliban in Afghanistan - although he insists he did not want to be a terrorist.

With him came coffee cart vendor Najibullah Zazi and yellow cab driver Zarein Ahmedzay, "angry at the US military presence in Afghanistan," according to prosecutor James Loonam.

Zazi and Ahmedzay have pleaded guilty and are testifying against Medunjanin in hopes of receiving lighter sentences.

In court, they described being radicalized while listening on CDs and on their iPods to lectures by Anwar al-Awlak, the assassinated US-born preacher who encouraged lone-wolf terrorists.

"I was convinced by these lectures at that time that it was a personal duty to fight," Ahmedzay said. "I became very radical."

In the summer of 2008, sitting in a car outside a mosque in Queens, the three made a "covenant" to join the Taliban, Ahmedzay said.

Yet immediately they were out of their depth. They failed to cross the Pakistani-Afghan border and instead of the Taliban found another group: Al-Qaeda.

Prosecutors say Al-Qaeda took them to a training camp, but in reality this was a modest facility where they performed perhaps less than an hour actually firing weapons. Al-Qaeda handlers clearly had other ideas.

"They were potentially very valuable to them (Al-Qaeda): They had American passports," Loonam said.

"If they could return to the United States to do something, anything, it could be a tremendous victory."

The plan, according to Zazi and Ahmedzay in their guilty pleas, was to set off explosions in New York's crowded subway, allegedly with Medunjanin wearing one of the bombs.

Back in America, Zazi, the bomb maker, sourced chemicals such as acetone to use in a homemade device. But almost laughably he reported running into trouble because he'd lost a page from his instructional notes.

When he correctly guessed that the FBI was on his trail, he and Ahmedzay frantically disposed of their bomb ingredients down toilets.

One by one they were arrested. Medunjanin panicked and, according to prosecutors, attempted one last hapless attempt to become the suicide bomber of his dreams: trying to crash his car on a busy New York highway.

Terrorism expert Risa Brooks, at Marquette University in California, said increasing US security measures keep amateur terrorists from getting better.

An example, she said, was the failure by Faisal Shahzad in his 2010 car bomb attempt in New York's Times Square. The poorly made bomb literally fizzled out and Shahzad fled by train, having forgotten the keys to his get-away car.

"There are numerous sub-steps involved in terrorism. In each of these steps, there is a small probability of detection. You have to develop skills to avoid being detected," Brooks said.

Researcher Michael Kenny said "terrorism requires knowledge." But he warned: "Dumb is deadly."

A trial underway in New York against a man accused in a 2009 suicide bomb attempt is exploring what the government calls one of the most serious terrorist plots on US soil since September 11, 2001.

But the case against Adis Medunjanin, 28, has also bared the wider world of homegrown US terrorism, a world of fanatical, bumbling Al Qaeda wannabes, and a law enforcement machine so tight that those jihad dreams rarely get put into action.

Ninety six attempted terrorist plots have been hatched on US soil since 9/11, experts say. Of these, only 11 can "generously" be classified as feasible, said Brian Jenkins, at the Rand Corporation.

"American jihadists bark, brag, sniff at edges, but are skittish and more closely resemble stray dogs than lone wolves," Mr Jenkins said.

The unprofessionalism, however, is also what makes them so hard to identify, resulting in a "more diffused threat," Mr Jenkins added.

Medunjanin and his two Flushing High School friends fitted that description perfectly.

Almost stereotypical working class New Yorkers, they came from immigrant families, were sports mad, strived to get an education, and worked classic entry-level jobs.

Medunjanin, now facing life in prison if convicted on all counts, came to New York as a child when his Muslim family fled Bosnia during the war against the Serbs in the early 1990s. Pudgy, but sporty, intelligent and said to possess natural leadership skills, he was on a good trajectory.

On 9/11, he was 17. "He was appalled by what he witnessed, as everyone else was," his defence attorney Robert Gottlieb said at the trial, which started on Monday.

But amid shockwaves from the US invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, the increasingly devout Medunjanin became angry.

At home, "he saw and suffered what can only be described as a wave of anti-Muslim hatred," Mr Gottlieb said. On television and on the Internet, he "heard about the drone attacks, the unmanned planes that drop bombs in Afghanistan.... He heard about the atrocities."

Finally, "he felt the need to come to the aid of his religion." By 2008, this mild-mannered Manhattan doorman was on a plane to Pakistan to join the Taliban in Afghanistan - although he insists he did not want to be a terrorist.

With him came coffee cart vendor Najibullah Zazi and yellow cab driver Zarein Ahmedzay, "angry at the US military presence in Afghanistan," according to prosecutor James Loonam.

Zazi and Ahmedzay have pleaded guilty and are testifying against Medunjanin in hopes of receiving lighter sentences.

In court, they described being radicalized while listening on CDs and on their iPods to lectures by Anwar al-Awlak, the assassinated US-born preacher who encouraged lone-wolf terrorists.

"I was convinced by these lectures at that time that it was a personal duty to fight," Ahmedzay said. "I became very radical."

In the summer of 2008, sitting in a car outside a mosque in Queens, the three made a "covenant" to join the Taliban, Ahmedzay said.

Yet immediately they were out of their depth. They failed to cross the Pakistani-Afghan border and instead of the Taliban found another group: Al-Qaeda.

Prosecutors say Al-Qaeda took them to a training camp, but in reality this was a modest facility where they performed perhaps less than an hour actually firing weapons. Al-Qaeda handlers clearly had other ideas.

"They were potentially very valuable to them (Al-Qaeda): They had American passports," Loonam said.

"If they could return to the United States to do something, anything, it could be a tremendous victory."

The plan, according to Zazi and Ahmedzay in their guilty pleas, was to set off explosions in New York's crowded subway, allegedly with Medunjanin wearing one of the bombs.

Back in America, Zazi, the bomb maker, sourced chemicals such as acetone to use in a homemade device. But almost laughably he reported running into trouble because he'd lost a page from his instructional notes.

When he correctly guessed that the FBI was on his trail, he and Ahmedzay frantically disposed of their bomb ingredients down toilets.

One by one they were arrested. Medunjanin panicked and, according to prosecutors, attempted one last hapless attempt to become the suicide bomber of his dreams: trying to crash his car on a busy New York highway.

Terrorism expert Risa Brooks, at Marquette University in California, said increasing US security measures keep amateur terrorists from getting better.

An example, she said, was the failure by Faisal Shahzad in his 2010 car bomb attempt in New York's Times Square. The poorly made bomb literally fizzled out and Shahzad fled by train, having forgotten the keys to his get-away car.

"There are numerous sub-steps involved in terrorism. In each of these steps, there is a small probability of detection. You have to develop skills to avoid being detected," Brooks said.

Researcher Michael Kenny said "terrorism requires knowledge." But he warned: "Dumb is deadly."

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world