North Korea has conducted at least 20 missile tests and one nuclear test in 2017. (File photo)

Washington:

Just a few years ago, North Korea's weapons program was treated like a bad joke, better known for its duds, misfires and fakes than its ability to threaten the United States.

But in 2017, the North Korean weapons program stopped being funny. Instead, Pyongyang's persistent pursuit of ballistic missile and nuclear weapons technology led to serious talk about the risk of a devastating conflict between the United States and North Korea.

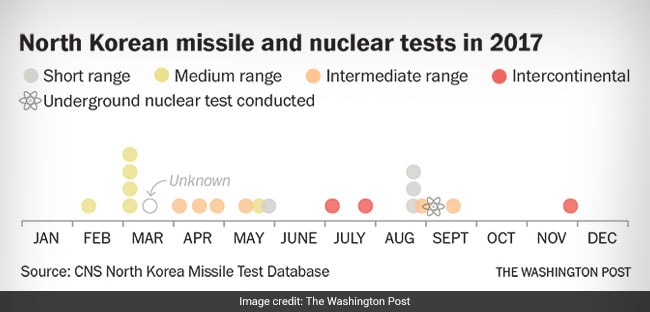

This change wasn't due to a sudden surge in North Korean tests or a change in leader Kim Jong Un's stance. In fact, data collected by researchers show that the number of tests in 2017 is similar to the number last year, while the bellicose threats made against the United States and others are consistent.

Building on decades of tests, North Korea has made remarkable technological gains in the past year, despite diplomatic and economic isolation. In the space of just a few months, Pyongyang conducted tests that showed it had boosted the range of its ballistic missiles and increased the yield of its nuclear weapons, as well as other more subtle advances that shocked outside observers.

Building on decades of tests, North Korea has made remarkable technological gains in the past year, despite diplomatic and economic isolation. In the space of just a few months, Pyongyang conducted tests that showed it had boosted the range of its ballistic missiles and increased the yield of its nuclear weapons, as well as other more subtle advances that shocked outside observers.

A giant nuclear weapons test

North Korea tested only one nuclear weapon this year, as opposed to two last year. However, the size of the weapon tested Sept. 3 dwarfed all previous tests - most experts agree that the bomb's yield, or the energy generated by the blast, was at least 140 kilotons. Some respected analysts have even pegged it at 250 kilotons.

If the higher estimate is true, that would mean that North Korea has a bomb almost 17 times the size of the one that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945. For comparison, the biggest weapon tested by North Korea before this year was between 10 kilotons and 20 kilotons.

David Wright, co-director of the global security program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said he believes that the Sept. 3 bomb was a "real H-Bomb" - suggesting that North Korea wasn't lying when it said it had created a two-stage thermonuclear device shortly before this test. If this is true, it shows that North Korea has now mastered the more complicated technology that entered the U.S. and Soviet arsenals in the 1950s after the first wave of nuclear weapons.

Such a device dramatically increases the damage that could be inflicted on a city. It also could mean that North Korea's missile systems can afford to be significantly less accurate when used in a real-life attack because the blast itself would be so much bigger.

An increased missile range

Although North Korea has conducted only one nuclear test in 2017, it has conducted at least 20 missile tests.

In July, experts warned that some of its long-range missiles looked like intercontinental ballistic missiles - meaning that they would have a range of more than 3,400 miles. Those fears were confirmed Nov. 28, when North Korea tested its Hwasong-15 missile. This enormous missile flew 54 minutes and traveled about 596 miles on a lofted trajectory. Its likely range was 8,100 miles - which would include the entire United States.

The advance is significant - last year, the longest-range missile North Korea had tested had a range of just 2,500 miles. Wright notes that this older missile, known as the Musudan, was the first that had gone significantly past the Scud missile technology first developed by the Soviets but that it had problems with reliability. After failed tests in 2016, North Korea appears to have shut down the Musudan program and replaced it with something better.

It is not clear whether North Korea can make a thermonuclear device small enough to fit on the end of the new missile, but many suspect that North Korea will soon gain this ability - if it hasn't already. "I believe we have to assume it can," James M. Acton, a physicist and co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told The Washington Post shortly after the Sept. 3 test.

More new missiles tested

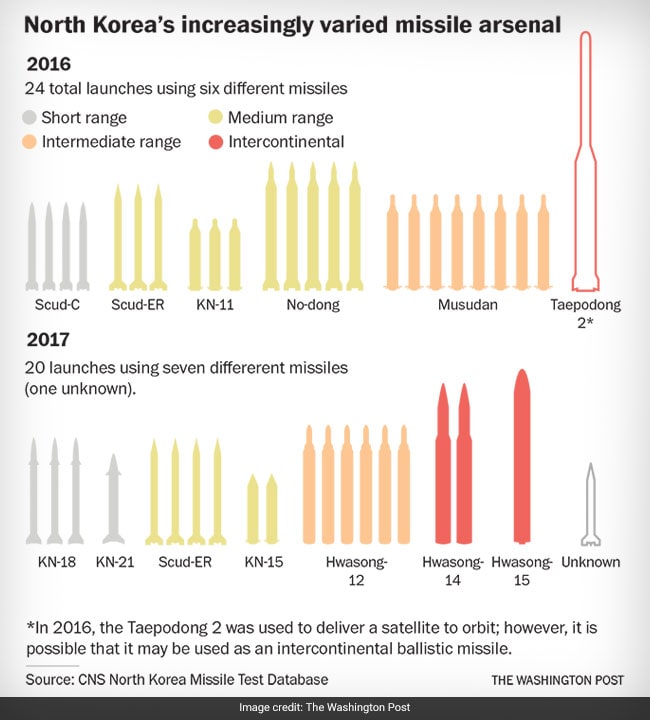

North Korea's missile program has been around for decades, but the sheer number of new missiles unveiled in 2017 shocked experts. "This year didn't see a record number of strategic missile tests, but it did see a record number of new missiles," said Shea Cotton, a research associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. "In fact, most of the missile systems tested this year we hadn't seen before."

In just one year, Cotton said, Kim Jong Un has unveiled six new missile systems. In contrast, his father, Kim Jong Il, tested only two new missiles during his time as leader, and North Korean founder Kim Il Sung tested three. "While I'm sure most of these new systems have been in the works for the past few years," Cotton said of this year's tests, "I'll give credit where credit is due. That is impressive as hell."

Others agreed. "From the late 1980s until 2016, all we saw were variant of Soviet Scuds," Wright said, but North Korea's missiles were now starting to look like modern missiles, with things like movable nozzles on their engines to steer the missiles. Importantly, two of the land-based missiles tested this year - the KN-15s - used solid fuel, rather than liquid fuel.

This is an important development as solid fuel can be left in a missile, meaning that it doesn't have to be fueled before it is launched.

"Solid-fueled missiles can be launched much more quickly and from mobile launchers, thereby enhancing the survivability of Pyongyang's missile arsenal," said Kingston Reif, director of disarmament and threat reduction policy at the Arms Control Association. "The ability to load and launch with minimal warning would put strain on the ability of missile defenses to get an early track on the missile."

What's next?

North Korea's weapons program advances in 2017 were not widely anticipated. But what about 2018? If North Korea continues on its current course without being interrupted, experts think it will make further advances within a year.

North Korea may test new missile technology, such as another that uses solid-state fuel, further advancing how effective its missiles would be in a real-life setting. It may also conduct more military exercises around missile launches or launching a volley with multiple missiles going up at once - essentially, allowing it to practice the sort of procedure that would happen in a real launch.

Cotton suggests that if things continue at this rate, North Korea could probably build up to a bigger event: what has been called the "Juche bird," a test of a missile loaded with a live nuclear weapon, probably above the Pacific Ocean. "A lot of folks in the U.S. have said North Korea still lacks the capability to put it all together," Cotton said. "North Korea has made several statements suggesting they think they might need to show us once and for all that they do have that capability."

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

But in 2017, the North Korean weapons program stopped being funny. Instead, Pyongyang's persistent pursuit of ballistic missile and nuclear weapons technology led to serious talk about the risk of a devastating conflict between the United States and North Korea.

This change wasn't due to a sudden surge in North Korean tests or a change in leader Kim Jong Un's stance. In fact, data collected by researchers show that the number of tests in 2017 is similar to the number last year, while the bellicose threats made against the United States and others are consistent.

Add image caption here

A giant nuclear weapons test

North Korea tested only one nuclear weapon this year, as opposed to two last year. However, the size of the weapon tested Sept. 3 dwarfed all previous tests - most experts agree that the bomb's yield, or the energy generated by the blast, was at least 140 kilotons. Some respected analysts have even pegged it at 250 kilotons.

If the higher estimate is true, that would mean that North Korea has a bomb almost 17 times the size of the one that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945. For comparison, the biggest weapon tested by North Korea before this year was between 10 kilotons and 20 kilotons.

David Wright, co-director of the global security program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said he believes that the Sept. 3 bomb was a "real H-Bomb" - suggesting that North Korea wasn't lying when it said it had created a two-stage thermonuclear device shortly before this test. If this is true, it shows that North Korea has now mastered the more complicated technology that entered the U.S. and Soviet arsenals in the 1950s after the first wave of nuclear weapons.

Such a device dramatically increases the damage that could be inflicted on a city. It also could mean that North Korea's missile systems can afford to be significantly less accurate when used in a real-life attack because the blast itself would be so much bigger.

An increased missile range

Although North Korea has conducted only one nuclear test in 2017, it has conducted at least 20 missile tests.

In July, experts warned that some of its long-range missiles looked like intercontinental ballistic missiles - meaning that they would have a range of more than 3,400 miles. Those fears were confirmed Nov. 28, when North Korea tested its Hwasong-15 missile. This enormous missile flew 54 minutes and traveled about 596 miles on a lofted trajectory. Its likely range was 8,100 miles - which would include the entire United States.

The advance is significant - last year, the longest-range missile North Korea had tested had a range of just 2,500 miles. Wright notes that this older missile, known as the Musudan, was the first that had gone significantly past the Scud missile technology first developed by the Soviets but that it had problems with reliability. After failed tests in 2016, North Korea appears to have shut down the Musudan program and replaced it with something better.

It is not clear whether North Korea can make a thermonuclear device small enough to fit on the end of the new missile, but many suspect that North Korea will soon gain this ability - if it hasn't already. "I believe we have to assume it can," James M. Acton, a physicist and co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told The Washington Post shortly after the Sept. 3 test.

More new missiles tested

North Korea's missile program has been around for decades, but the sheer number of new missiles unveiled in 2017 shocked experts. "This year didn't see a record number of strategic missile tests, but it did see a record number of new missiles," said Shea Cotton, a research associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. "In fact, most of the missile systems tested this year we hadn't seen before."

In just one year, Cotton said, Kim Jong Un has unveiled six new missile systems. In contrast, his father, Kim Jong Il, tested only two new missiles during his time as leader, and North Korean founder Kim Il Sung tested three. "While I'm sure most of these new systems have been in the works for the past few years," Cotton said of this year's tests, "I'll give credit where credit is due. That is impressive as hell."

Others agreed. "From the late 1980s until 2016, all we saw were variant of Soviet Scuds," Wright said, but North Korea's missiles were now starting to look like modern missiles, with things like movable nozzles on their engines to steer the missiles. Importantly, two of the land-based missiles tested this year - the KN-15s - used solid fuel, rather than liquid fuel.

This is an important development as solid fuel can be left in a missile, meaning that it doesn't have to be fueled before it is launched.

"Solid-fueled missiles can be launched much more quickly and from mobile launchers, thereby enhancing the survivability of Pyongyang's missile arsenal," said Kingston Reif, director of disarmament and threat reduction policy at the Arms Control Association. "The ability to load and launch with minimal warning would put strain on the ability of missile defenses to get an early track on the missile."

What's next?

North Korea's weapons program advances in 2017 were not widely anticipated. But what about 2018? If North Korea continues on its current course without being interrupted, experts think it will make further advances within a year.

North Korea may test new missile technology, such as another that uses solid-state fuel, further advancing how effective its missiles would be in a real-life setting. It may also conduct more military exercises around missile launches or launching a volley with multiple missiles going up at once - essentially, allowing it to practice the sort of procedure that would happen in a real launch.

Cotton suggests that if things continue at this rate, North Korea could probably build up to a bigger event: what has been called the "Juche bird," a test of a missile loaded with a live nuclear weapon, probably above the Pacific Ocean. "A lot of folks in the U.S. have said North Korea still lacks the capability to put it all together," Cotton said. "North Korea has made several statements suggesting they think they might need to show us once and for all that they do have that capability."

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world