Out of work, William Peter Blatty sat down at a typewriter and, wrote "The Exorcist."

William Peter Blatty was a senior at Georgetown University in 1949 when he heard the extraordinary story that, more than two decades later, would change his life - and scare the devil out of everyone else.

One of the priests at the university told him about a case from nearby Prince George's County in which a 14-year-old boy seemed to be possessed by a demon. After months of solemn rites of exorcism by Catholic priests, the demon appeared to be expelled.

Blatty went on to sell vacuum cleaners, drive a beer truck and serve in the Air Force before becoming a comic novelist and a screenwriter in Hollywood. Years later, out of work and out of ideas, he sat down at a typewriter and, as if possessed himself, wrote "The Exorcist."

Changing the central character to a 12-year-old girl living in Georgetown, he produced a dark theological thriller that became an international blockbuster when it was published in 1971. The 1973 film version, for which Blatty won an Academy Award for his screenplay, revolutionized the genre of horror movies and, thanks to head-spinning special effects and the acting of young Linda Blair, became a pop-culture phenomenon.

Blatty, 89, died Jan. 12 at a hospital near his home in Bethesda, Maryland. The cause was multiple myeloma, a form of blood cancer, said his wife, Julie Blatty.

From the beginning, Blatty knew he had something special with "The Exorcist."

From the beginning, Blatty knew he had something special with "The Exorcist."

"I couldn't wait to finish it and become famous," he told People magazine.

"The eyes gleamed fiercely, unblinking," he wrote in one evocative passage about his main character, Regan MacNeil, "and a yellowish saliva dribbled down from a corner of her mouth to her chin. Then her lips stretched taut into a feral grin, into bow-mouthed mockery. 'Well, well, well,' gloated Regan sardonically. . . . 'So, it's you.' "

A scathing review in Time magazine proved prophetic in a backhanded way: "It is a pretentious, tasteless, abominably written, redundant pastiche of superficial theology, comic-book psychology, Grade C movie dialogue and Grade Z scatology. In short, The Exorcist will be a bestseller and almost certainly a drive-in movie."

When there was an unexpected opening on Dick Cavett's late-night talk show, Blatty was summoned as an emergency guest. He and Cavett ended up discussing demons, exorcism and Catholic theology for 45 minutes.

From that moment on, people couldn't get enough of "The Exorcist." It was on bestseller lists for over a year, eventually selling more than 13 million copies in the United States alone. It was translated into dozens of languages.

When Blatty sold the film rights, he demanded and received full artistic control as producer. The movie, directed by William Friedkin, was filmed largely in Georgetown. The cast included Max von Sydow, Lee Cobb and Ellen Burstyn, but the breakout star was the 13-year-old Blair as demon-beset Regan MacNeil.

Hollywood makeup master Dick Smith created some of the film's most shocking effects, such as bulging eyes, rotting teeth, projectile vomiting and a head that could rotate 360 degrees. The film's musical theme, Mike Oldfield's eerie "Tubular Bells," added a haunting quality of its own.

The Catholic Church generally overlooked the blasphemy in the book and movie, including Blair's unauthorized use of a crucifix and the profane epithets coming from her mouth.

Critics sharpened their knives, often dismissing the film as exploitative drivel. "Appallingly effective on the surface," Gary Arnold wrote in The Washington Post, " 'The Exorcist' is appallingly worthless beneath the surface."

Moviegoers didn't care. "The Exorcist" broke box office records everywhere it opened and was nominated for 10 Academy Awards. It won two, for Blatty's best adapted screenplay and best sound.

The book and movie also prompted a continuing debate about the validity of exorcism and whether people could in fact become embodiments of the devil in the flesh. Visitors flocked to Georgetown and in particular the long stone staircase where the film's climactic scene takes place.

"Nobody's going to expect this to happen here," Blatty told Washingtonian magazine in 2015, "and that's what I was trying to get across: This is not a horror story. This is real. Something really happened here in Washington, D.C., with ordinary life buzzing all around."

William Peter Blatty was born Jan. 7, 1928, in New York, the fifth and youngest child of Lebanese immigrants. He was a toddler when his parents split up, and he was raised by his strong-willed mother, who sold quince jelly on the streets of Manhattan.

"We never lived at the same address in New York for longer than two or three months at a time," Blatty told The Post in 1972. "Eviction was the order of the day."

After attending a Jesuit high school in Brooklyn, he received a scholarship to Georgetown, graduating in 1950 with a bachelor's degree in English. "Those years at Georgetown were probably the best years of my life," he said in 2015. "Until then, I'd never had a home."

Unable to find a teaching job, Blatty sold vacuum cleaners door to door and drove a beer truck before enlisting in the Air Force, where his Arabic language skills proved useful. He received a master's degree in English from George Washington University in 1954, then worked for the U.S. Information Agency in Lebanon.

He began to contribute articles to magazines and, from 1957 to 1960, was a public relations specialist at the University of Southern California and Loyola University in Los Angeles. Partly as a gag and partly as an unsuccessful ploy to become an actor, Blatty passed himself off as the wayward son of a Saudi prince, fooling many people in L.A. high society.

He wrote about the experience for the Saturday Evening Post and published several comic novels in the 1960s that had lukewarm reviews and modest sales. A 1963 novel, "John Goldfarb, Please Come Home," and a 1965 movie of the same name triggered a legal imbroglio after Blatty portrayed an Arab football team beating Notre Dame.

Officials of the Fighting Irish sued for unauthorized use of the college's name, but courts ultimately ruled in Blatty's favor.

He found more success as a screenwriter, most notably with "A Shot in the Dark" (1964), one of the slapstick Pink Panther movies directed by Blake Edwards, with Peter Sellers as the hapless Inspector Clouseau.

Blatty wrote screenplays for other films, including "What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?" (1966) and the espionage musical "Darling Lili" (1970), both directed by Edwards, before the monumental success of "The Exorcist."

In 1980, Blatty wrote the screenplay for "The Ninth Configuration" (also known as "Twinkle, Twinkle, 'Killer' Kane"), based on a novel he wrote in 1966. He also wrote and directed "The Exorcist III" in 1990.

Blatty disagreed with Friedkin's original ending of "The Exorcist," and in 2000 a longer, but not necessarily improved, version was released. The Fox TV series "The Exorcist," based on Blatty's work, debuted in 2016.

After years in Hollywood and Aspen, Colorado, Blatty settled in Bethesda in 2000. He went on to write other novels and nonfiction books, including "Finding Peter: A True Story of the Hand of Providence and Evidence of Life After Death" (2015), which explored paranormal experiences that Blatty believed brought him closer to his son Peter, who died of a heart ailment in 2006 at age 19.

Blatty's marriages to Mary Rigard, Elizabeth Gilman and professional tennis player Linda Tuero were dissolved. Survivors include his wife of 33 years, Julie Witbrodt Blatty of Bethesda; and seven children from various marriages. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

In recent years, Blatty had a public dispute with Georgetown University, charging that it had abandoned its Catholic heritage. He organized a petition that he sent to the Vatican.

But Blatty remained inescapably linked with the book and movie that brought him the fame he sought for so long.

"I can't regret 'The Exorcist,' " he said in 2013.

"I always believe that there is a divine hand everywhere."

- - -

(The Washington Post's Adam Bernstein contributed to this report)

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

One of the priests at the university told him about a case from nearby Prince George's County in which a 14-year-old boy seemed to be possessed by a demon. After months of solemn rites of exorcism by Catholic priests, the demon appeared to be expelled.

Blatty went on to sell vacuum cleaners, drive a beer truck and serve in the Air Force before becoming a comic novelist and a screenwriter in Hollywood. Years later, out of work and out of ideas, he sat down at a typewriter and, as if possessed himself, wrote "The Exorcist."

Changing the central character to a 12-year-old girl living in Georgetown, he produced a dark theological thriller that became an international blockbuster when it was published in 1971. The 1973 film version, for which Blatty won an Academy Award for his screenplay, revolutionized the genre of horror movies and, thanks to head-spinning special effects and the acting of young Linda Blair, became a pop-culture phenomenon.

Blatty, 89, died Jan. 12 at a hospital near his home in Bethesda, Maryland. The cause was multiple myeloma, a form of blood cancer, said his wife, Julie Blatty.

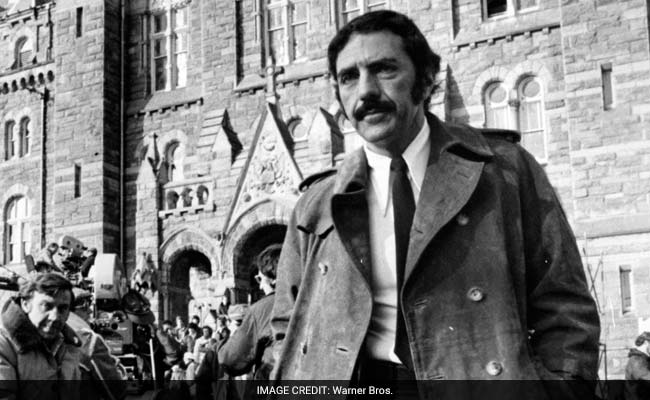

William Peter Blatty was author and producer of the film version of his best-selling novel "The Exorcist"

"I couldn't wait to finish it and become famous," he told People magazine.

"The eyes gleamed fiercely, unblinking," he wrote in one evocative passage about his main character, Regan MacNeil, "and a yellowish saliva dribbled down from a corner of her mouth to her chin. Then her lips stretched taut into a feral grin, into bow-mouthed mockery. 'Well, well, well,' gloated Regan sardonically. . . . 'So, it's you.' "

A scathing review in Time magazine proved prophetic in a backhanded way: "It is a pretentious, tasteless, abominably written, redundant pastiche of superficial theology, comic-book psychology, Grade C movie dialogue and Grade Z scatology. In short, The Exorcist will be a bestseller and almost certainly a drive-in movie."

When there was an unexpected opening on Dick Cavett's late-night talk show, Blatty was summoned as an emergency guest. He and Cavett ended up discussing demons, exorcism and Catholic theology for 45 minutes.

From that moment on, people couldn't get enough of "The Exorcist." It was on bestseller lists for over a year, eventually selling more than 13 million copies in the United States alone. It was translated into dozens of languages.

When Blatty sold the film rights, he demanded and received full artistic control as producer. The movie, directed by William Friedkin, was filmed largely in Georgetown. The cast included Max von Sydow, Lee Cobb and Ellen Burstyn, but the breakout star was the 13-year-old Blair as demon-beset Regan MacNeil.

Hollywood makeup master Dick Smith created some of the film's most shocking effects, such as bulging eyes, rotting teeth, projectile vomiting and a head that could rotate 360 degrees. The film's musical theme, Mike Oldfield's eerie "Tubular Bells," added a haunting quality of its own.

The Catholic Church generally overlooked the blasphemy in the book and movie, including Blair's unauthorized use of a crucifix and the profane epithets coming from her mouth.

Critics sharpened their knives, often dismissing the film as exploitative drivel. "Appallingly effective on the surface," Gary Arnold wrote in The Washington Post, " 'The Exorcist' is appallingly worthless beneath the surface."

Moviegoers didn't care. "The Exorcist" broke box office records everywhere it opened and was nominated for 10 Academy Awards. It won two, for Blatty's best adapted screenplay and best sound.

The book and movie also prompted a continuing debate about the validity of exorcism and whether people could in fact become embodiments of the devil in the flesh. Visitors flocked to Georgetown and in particular the long stone staircase where the film's climactic scene takes place.

"Nobody's going to expect this to happen here," Blatty told Washingtonian magazine in 2015, "and that's what I was trying to get across: This is not a horror story. This is real. Something really happened here in Washington, D.C., with ordinary life buzzing all around."

William Peter Blatty was born Jan. 7, 1928, in New York, the fifth and youngest child of Lebanese immigrants. He was a toddler when his parents split up, and he was raised by his strong-willed mother, who sold quince jelly on the streets of Manhattan.

"We never lived at the same address in New York for longer than two or three months at a time," Blatty told The Post in 1972. "Eviction was the order of the day."

After attending a Jesuit high school in Brooklyn, he received a scholarship to Georgetown, graduating in 1950 with a bachelor's degree in English. "Those years at Georgetown were probably the best years of my life," he said in 2015. "Until then, I'd never had a home."

Unable to find a teaching job, Blatty sold vacuum cleaners door to door and drove a beer truck before enlisting in the Air Force, where his Arabic language skills proved useful. He received a master's degree in English from George Washington University in 1954, then worked for the U.S. Information Agency in Lebanon.

He began to contribute articles to magazines and, from 1957 to 1960, was a public relations specialist at the University of Southern California and Loyola University in Los Angeles. Partly as a gag and partly as an unsuccessful ploy to become an actor, Blatty passed himself off as the wayward son of a Saudi prince, fooling many people in L.A. high society.

He wrote about the experience for the Saturday Evening Post and published several comic novels in the 1960s that had lukewarm reviews and modest sales. A 1963 novel, "John Goldfarb, Please Come Home," and a 1965 movie of the same name triggered a legal imbroglio after Blatty portrayed an Arab football team beating Notre Dame.

Officials of the Fighting Irish sued for unauthorized use of the college's name, but courts ultimately ruled in Blatty's favor.

He found more success as a screenwriter, most notably with "A Shot in the Dark" (1964), one of the slapstick Pink Panther movies directed by Blake Edwards, with Peter Sellers as the hapless Inspector Clouseau.

Blatty wrote screenplays for other films, including "What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?" (1966) and the espionage musical "Darling Lili" (1970), both directed by Edwards, before the monumental success of "The Exorcist."

In 1980, Blatty wrote the screenplay for "The Ninth Configuration" (also known as "Twinkle, Twinkle, 'Killer' Kane"), based on a novel he wrote in 1966. He also wrote and directed "The Exorcist III" in 1990.

Blatty disagreed with Friedkin's original ending of "The Exorcist," and in 2000 a longer, but not necessarily improved, version was released. The Fox TV series "The Exorcist," based on Blatty's work, debuted in 2016.

After years in Hollywood and Aspen, Colorado, Blatty settled in Bethesda in 2000. He went on to write other novels and nonfiction books, including "Finding Peter: A True Story of the Hand of Providence and Evidence of Life After Death" (2015), which explored paranormal experiences that Blatty believed brought him closer to his son Peter, who died of a heart ailment in 2006 at age 19.

Blatty's marriages to Mary Rigard, Elizabeth Gilman and professional tennis player Linda Tuero were dissolved. Survivors include his wife of 33 years, Julie Witbrodt Blatty of Bethesda; and seven children from various marriages. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

In recent years, Blatty had a public dispute with Georgetown University, charging that it had abandoned its Catholic heritage. He organized a petition that he sent to the Vatican.

But Blatty remained inescapably linked with the book and movie that brought him the fame he sought for so long.

"I can't regret 'The Exorcist,' " he said in 2013.

"I always believe that there is a divine hand everywhere."

- - -

(The Washington Post's Adam Bernstein contributed to this report)

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world